A Larger Suitcase

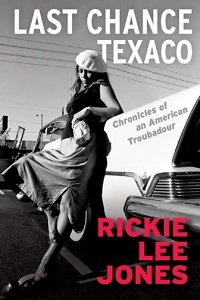

Rickie Lee Jones recalls her family and career in Last Chance Texaco

Memoirs and biopics about famous musicians follow a common arc. It all starts with a quick summation of the artist’s humble beginnings. Then, there’s the nostalgic depiction of their ascent to stardom followed by a perils-of-fame period. Ultimately, we end with heartwarming scenes of redemption and a comeback tour. Dotted with glamorous anecdotes about famous friends and lifetime achievement awards, these books are fun but formulaic.

Rickie Lee Jones gives us something entirely different with Last Chance Texaco: Chronicles of an American Troubadour. Jones’ memoir focuses on her childhood and family history, only briefly touching on the earliest phases of her career when she was, as the book notes, “launched into the public as a fully-developed rock icon.” I spoke to the legendary pop savant ahead of her virtual event with the 2021 Southern Festival of Books.

Jones always meant for her memoir to be, as she explains, “the story of one American family.” “The stories of our lives had become mythology,” she says. “They had been told so many times amongst us.” Ten years ago, she had the first inkling to commit the Jones family history to the page, starting with her mother Bettye. As she writes in the book, “My mother’s stories are the heart of me, the country from which I come. Escapades of her ghastly childhood in the orphanage were the Grimm’s Fairy Tales of my own.” Readers are treated to these horrific tales of child poverty, an experience that hardened young Bettye in the Depression-era Midwest.

Much of Jones’ musical world is populated with tragic, morally conflicted characters. Her dad, Richard, a WWII vet and artist, could be one of them. Richard grew up in a show business family. His father, Frank “Peg Leg” Jones, was a famous one-legged performer on the Chicago vaudeville circuit. As a boy, Richard hopped a train to escape the violent Peg Leg, pursuing a “hobo” existence and taking what Jones describes as “the hard road of adventure.” Richard and Bettye’s paths crossed in Chicago, where they started a family and gave birth to Jones in 1954.

While Jones’ tone is at times wistful, she writes with a lucidity that makes her an authoritative, precise narrator. These are her family’s stories; she sees herself as a guardian of them. “I never, as a kid, talked about any of these things, nor when I became famous,” she says. Her admiration for her hardscrabble, devoted working-class parents sits right next to the instability and violence she experienced under their roof.

While Jones’ tone is at times wistful, she writes with a lucidity that makes her an authoritative, precise narrator. These are her family’s stories; she sees herself as a guardian of them. “I never, as a kid, talked about any of these things, nor when I became famous,” she says. Her admiration for her hardscrabble, devoted working-class parents sits right next to the instability and violence she experienced under their roof.

Richard struggled with PTSD and alcoholism. In one scene, he beats a teenage Rickie for wearing a supposedly immodest outfit around the neighborhood boys. A few years and chapters later, he drives across the country to bail her out of a Detroit jail and takes her in when Bettye refuses. Her “secretive” and “unpredictable” mother is the book’s most fascinating character. She’s a fierce matriarch, a force of love and rage. Jones writes, “One day Mom would fight for me like a lioness, the next she would slap me for spilling my milk.” Even after 100 pages of getting to know Richard and Bettye, it’s hard to know what to make of them.

This could be intentional. Conclusions feel useless when it comes to something as complex as family, and Jones makes us consider this in Last Chance Texaco. “In my story, there is no bad guy. At some points in people’s lives they behave extraordinarily wonderful, and sometimes they behave badly. I wanted to tell that and not make them into villains or superheroes,” she says.

Jones believes she’s “sculpted” the story the best she can to keep readers from harshly judging her parents. At 66, she brings new perspective to her childhood: “Some of us are born to live lives on an exaggerated scale. Even as children we have a larger suitcase in which to carry all the things that will one day be on our backs.”

The suitcase is an apt metaphor. Her parents gave her the gift — or curse — of an undying sense of wanderlust. Last Chance Texaco recounts the family taking to the road when Jones is 4. “Once they left Chicago they never stopped moving,” she writes. They head off to Arizona to answer the “siren call of the West.”

As a teen, Jones goes full-hippie and flees home, hitchhiking along California’s Highway 1 in the summer of 1969. She survives creeps, jail, and almost freezing to death. In 1973, the emancipated 18-year-old steps onto the dilapidated boardwalks of Venice Beach for the first time. Tanned and braless, it’s here that she starts her transformation from nowhere girl to overnight success.

In 1979, Jones released her debut album and graced the cover of Rolling Stone. She played Saturday Night Live, won the Grammy for Best New Artist, and the record went platinum. All of this is remembered in Last Chance Texaco. But so is the fact that she never achieved the same commercial or cultural significance again. The woman with the red beret, once deemed the “Duchess of Coolsville,” floated into obscurity only two albums into her career.

The memoir follows her as she takes the unglamorous road of recovery and overcomes a heroin addiction in the early 80s. Inextricably tied to Tom Waits, the brooding lord of Venice Beach, Jones schlepps around the moniker “Tom Waits’ one-time girlfriend” for much too long, her career marked by not-so-subtle-sexism and associations with a man she dated for a year.

“I think before I wrote [the book] I might have had an axe to grind,” Jones tells me. But in writing Last Chance Texaco, that time of her life as a famous young woman has begun to “sparkle in a beautiful way,” she says. The process of writing the memoir “was heartbreaking and difficult, but as with all things, now that it’s over, it just seemed like it was great.”

After 40 years as a recording artist, Jones maintains a disarming, Teflon optimism. “Conquering an impossible survival is such a moving experience that it becomes a new reason for life,” she writes in the memoir. Over and over, Jones finds those reasons to keep living her remarkable life.

Jacqueline Zeisloft is a writer and editor whose work has appeared in the Nashville Scene and the Women’s Review of Books. She holds a B.A. in English literature from Belmont University. She lives in New York City.