A License to Lie

Internationally acclaimed South African poet Antjie Krog talks with Chapter 16 about the essential instability of the first-person voice

Internationally acclaimed journalist, poet, and playwright Antjie Krog was born into a family of Afrikaner writers and grew up on a farm within a conservative Afrikaans-speaking community. She published her first book at age seventeen and since then has continued to write groundbreaking work about South African injustices. She has written plays, books for children, many works of nonfiction, and thirteen volumes of poetry, two of which have been translated into English: Body Bereft (2006) and Down to My Last Skin (2000).

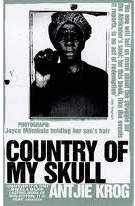

Perhaps Krog’s best-known book in the United States is Country of My Skull, a work of nonfiction which weaves together testimonies of both the victims and perpetrators of apartheid. The book, first released in 1998, was later adapted to the screen and re-titled In My Country. It was widely praised: “It is doubtful that a better book will be written about South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission,” noted Foreign Affairs.

Krog’s writing, regardless of genre, is characterized by an attention to detail, an experimentation with form, and an integration of political and personal concerns. The poem “Alphabet,” for example, admits frustration with the politics of South Africa and with the limits of poetry itself, but at the same time it emphasizes the ways in which writing can serve as an instrument of change: “Here I am learning to write,” the speaker says. “I can’t do otherwise.”

Krog answered questions from Chapter 16 via email in anticipation of her appearances at Rhodes College in Memphis on November 15 and 16.

Chapter 16: Country of My Skull and A Change of Tongue have been widely praised for the form the books take, a postmodern hybrid of fiction, memoir, and reportage. How did you arrive at this innovative form? Or was it less of a conscious choice, something that emerged organically from the material itself?

Antjie Krog: I reported for two years as a journalist on a daily basis about the Truth Commission. In other words, I sent factual reports through to the news and current-affairs programs. Even asked now and then to give a personal impression, one was loathe to do so, as one keenly felt that one had no right to talk about one’s own feelings amidst so many people who have paid so costly for every single word they uttered.

Antjie Krog: I reported for two years as a journalist on a daily basis about the Truth Commission. In other words, I sent factual reports through to the news and current-affairs programs. Even asked now and then to give a personal impression, one was loathe to do so, as one keenly felt that one had no right to talk about one’s own feelings amidst so many people who have paid so costly for every single word they uttered.

After the commission, I felt absolutely compelled to deal with my own responsibility, guilt, emotions, family, and privilege. Up until that moment, I had published ten volumes of Afrikaans poetry and received all the major prizes for it. So my initial instinct was to see what/how it could be poetry. Then a publisher who heard my reporting on the TRC approached me to write a book. “I cannot,” I said. “I cannot write prose, and I cannot express myself to that extent in English.” “Write it in Afrikaans and we will see.”

So the book inevitably was driven by something else than mere factual reporting. But to tell a story (and not a news report), you have no choice but to use the devices of storytelling: a beginning, middle, end. Some trace-able characters, some gripping moments followed by relief, etc. The moment you start telling a story, you start to falsify/fictionalize. I thought I had to give account in the book itself of the fact that I am aware of that. I also had to protect people who told me things in confidence, or family members who had never asked to be in a book, so I changed names and places. Using the word “I” is on the one hand a license to lie—Who on earth is this I? The I changes from this hour to the next)—and on the other hand, [it is] the most honest word I know.

Change of Tongue was somewhat different. The theme itself—namely change/transformation/becoming something else—begged for “transformative writing.” So I opened every part with a completely fictionalized piece: becoming rain, becoming giraffe, becoming moonlight, becoming poor and black—ending in the physical black-and-white union. I did that also because I could not really find anything in real life that conveyed the idea of completely becoming other than oneself. The big question around writing nonfiction, or creative nonfiction, is, of course, ethical: where, why, how does the fiction part step in?

Change of Tongue was somewhat different. The theme itself—namely change/transformation/becoming something else—begged for “transformative writing.” So I opened every part with a completely fictionalized piece: becoming rain, becoming giraffe, becoming moonlight, becoming poor and black—ending in the physical black-and-white union. I did that also because I could not really find anything in real life that conveyed the idea of completely becoming other than oneself. The big question around writing nonfiction, or creative nonfiction, is, of course, ethical: where, why, how does the fiction part step in?

Chapter 16: What many readers respond to in your poetry is the way you situate yourself within the political issues; there doesn’t seem to be a division between author and politics in your work. Would you say that’s an accurate statement?

Antjie Krog: In South Africa, the private had always been political because apartheid cut into the personal sphere. But what was hard (and still is) is to find a “form” for what one wanted to say—especially within a context of many languages, a resentment towards my own language, various degrees of literacy, a dominating oral culture with oral poets being part of daily life and often making poetry on behalf of large communities. Sometimes one’s political work published in volumes of poetry bought in expensive bookshops becomes nothing more than private qualms.

Chapter 16: Some would call your work feminist in the way it openly considers women’s bodies and women’s life stages. Others would call that label problematic, arguing that the personal and political, the domestic and the international, are not separate spheres. What do you think?

Antjie Krog: An epic I wrote about a woman who lived for a few years in South Africa during the eighteenth century led to my being [called] anti-feminist because I used fertility charts and menstruation in the text. Within five years, it was hailed as a feminist text. So, I have learnt that it is foolish to tailor one’s text to what academics busy themselves with. If one scratches and grapples and pushes at the borders, one will arrive at something new.

Chapter 16: Your poem “New Alphabet,” which appeared in Poetry magazine, moves in ways that a lot of critics associate with your writing. It’s lyrical and cyclical, and it weaves together the personal and the political. But are there some aspects to your poetics that you feel are often overlooked in reviews?

Chapter 16: Your poem “New Alphabet,” which appeared in Poetry magazine, moves in ways that a lot of critics associate with your writing. It’s lyrical and cyclical, and it weaves together the personal and the political. But are there some aspects to your poetics that you feel are often overlooked in reviews?

Antjie Krog: The burden and curse of self-translation and the slippery plight of playing between languages.

Chapter 16: Your work educates readers not only about South African politics, but also about South African literature. Could you talk a little about the current preoccupations you see in South African poetry? And how your current work resists and engages with those trends?

Antjie Krog: South Africa is currently bursting at the seams with new up-and-coming black voices. New areas, birthplaces, intimate spaces are being opened up that were not three hundred years before. The texts in the nonfiction genre are overwhelming, of outstanding quality, and sell extraordinarily well. My guess is that we, who lived apart for so long, are keen to get to know those who lived in different ways and spaces.

Within poetry, it has become slightly more of a problem. During the old times, the dominant literary style and yardstick had been that of, shall we call it, English (as in Europe) poetry. Now there is a phalanx of oral poets, whose numbers are often enlarged by performance poets of England and the U.S. Although I had been deeply influenced by oral poetry in South Africa and have learnt my trade to perform (as in read) my own work from the indigenous poets, I do not fit the performance-poet role. So many of us find ourselves in one of two “camps”: the performance poet, preferred and supported by millions of black enthusiasts, appearing on big stages across the country, yet finding it hard to get a publisher or a good review; or being a “poet of the page,” and finding a publisher, positive reviews, but known only to those who buy poetry volumes.

Antjie Krog will give a lecture and a poetry reading in Memphis at Rhodes College. On November 15 at 6 p.m., she will present her lecture titled “Truth vs. Revenge: The Case of South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission” in the Blount Auditorium in Buckman Hall. On November 16 at 6 p.m., she will read her poetry at Frazier Jelke Building, Auditorium A. Both events are free and open to the public.