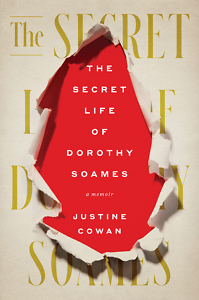

A Modern Mother’s Surprising Secret

In The Secret Life of Dorothy Soames, a daughter confronts her mother’s Dickensian childhood

Growing up in the 1970s, Justine Cowan knew her mother had a secret. “That was how I envisioned it — a hidden chamber tucked away in the recesses of my mother’s twisted mind,” she writes in The Secret Life of Dorothy Soames: A Memoir. Uncontainable, the secret “would ooze out like a thick slurry … covering our family in darkness.”

Sometimes her mother, Eileen, claimed noble Welsh ancestry. An accomplished painter and pianist who said she had studied at London’s Royal Academy of Music, she decorated the family’s San Francisco-area home with Old World furnishings. Ambitious for her daughter, she pressed Cowan into crack-of-dawn violin lessons, hired a private handwriting tutor, and insisted she learn to spell in the Queen’s English (“theatre” not “theater”). Publicly charming, she flew into rages at home, once throwing Cowan’s dollhouse against a wall. Cowan rebelled, never sure what was wrong.

One day, though, Cowan found her mother writing a name on a notepad: Dorothy Soames, Dorothy Soames, Dorothy Soames. It was her first clue.

The Secret Life of Dorothy Soames is the product of Cowan’s search for her mother’s past. Born out of wedlock in 1932 to an English farm girl who relinquished her to a London institution for “foundlings” — children whose parents could not keep them — Eileen grew up in circumstances reminiscent of a Charles Dickens novel. Established in the 18th century, the Foundling Hospital (actually a school) once offered a relatively compassionate alternative to tossing unwanted infants in sewers, but its centuries-old rules never changed. Starved and beaten, the children were raised to become laborers or servants to the upper classes. To hide their origins, they were assigned new names. “Dorothy Soames” was Eileen’s foundling name.

Cowan, an Atlanta environmental attorney who lived in Nashville after law school, is also the daughter and granddaughter of two former Tennessee state legislators from Rogersville, both named John Thompson. Eileen and the younger John met in San Francisco, where he moved in the 1950s. By then, Eileen had left the Foundling Hospital, shed her “Dorothy Soames” identity, and come to the United States. After they married, John’s income as an attorney enabled her to hide her past.

Finally wanting to reveal her story late in life, Eileen left a partial memoir, which Cowan weaves into her own narrative about their difficult relationship. As much social history as memoir, the book incorporates meticulous archival research and interviews with Eileen’s elderly former classmates gleaned from several trips to England. Cowan shows, vividly, the children’s regimented lives. Dressed in stiff brown serge, the girls lined up every morning in “crocodile formation” (pairs) and marched to the washroom, where they brushed their teeth in unison (“Taps on! … Brushes under! … And brush!” the supervisor barked). Next came breakfast, eaten in silence, followed by the toilets, where each girl was expected to produce “a solid” on command. Caned for speaking or accidentally dropping food, they were constantly shamed for their origins. Cowan imagines the boys, raised separately, had it worse.

Finally wanting to reveal her story late in life, Eileen left a partial memoir, which Cowan weaves into her own narrative about their difficult relationship. As much social history as memoir, the book incorporates meticulous archival research and interviews with Eileen’s elderly former classmates gleaned from several trips to England. Cowan shows, vividly, the children’s regimented lives. Dressed in stiff brown serge, the girls lined up every morning in “crocodile formation” (pairs) and marched to the washroom, where they brushed their teeth in unison (“Taps on! … Brushes under! … And brush!” the supervisor barked). Next came breakfast, eaten in silence, followed by the toilets, where each girl was expected to produce “a solid” on command. Caned for speaking or accidentally dropping food, they were constantly shamed for their origins. Cowan imagines the boys, raised separately, had it worse.

Reading The Secret Life of Dorothy Soames is like discovering that a 20th-century suburban mom grew up in the bleak Lowood School from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. That it also invokes Oliver Twist is unsurprising, since Dickens lived near the Foundling Hospital and was a benefactor. Cowan compares the school’s environment to Margaret Atwood’s dystopian The Handmaid’s Tale. For me, it brought to mind Sheila O’Connor’s Evidence of V, another memoir about the shame of “illegitimacy” in the 1930s. Cowan says her mother’s story exposes the long-term emotional consequences of powerful men decreeing what is right for women and children. And, one might add, of separating children from parents.

Fortunately, Dorothy/Eileen showed surprising pluck. She was often confined in a dark closet as punishment, but once, in a hurry, a teacher locked her in a room with windows, which she climbed out. She and another girl ran away. Intending to walk 20 miles to the other girl’s foster family, they encountered a kind stranger who bought them food and train tickets and gave them money (which they’d never seen). They were returned to the school, but another glimpse of the outside world came when Dorothy was chosen to attend a party for American soldiers, where she was astonished to be treated kindly. Eventually she was reclaimed by her mother, who had tried several times to get her out, succeeding only when World War II began. The Foundling Hospital closed soon thereafter.

In spite of her dogged research, Cowan wasn’t able to uncover all her mother’s secrets. Sadly, Eileen died before she and her daughter could heal their fraught relationship, though in writing the book, Cowan made sense of it. This remarkable story illustrates how our lives can be shaped by a past we may never imagine.

Jane Marcellus is a professor at Middle Tennessee State University, where she teaches media history and writing. Her essays have been listed as “Notable” in Best American Essays 2018, 2019, and 2020.