A New Mode of Being

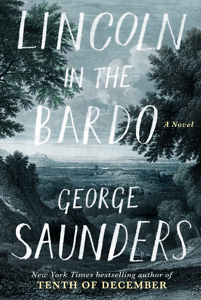

George Saunders’s long awaited first novel examines a president in crisis

February, 1862: Oak Ridge Cemetery in Georgetown. Just over a year has passed since the battle at Ft. Sumter. The Confederacy’s surprising tenacity has ensured a much longer, bloodier war than anyone predicted. And the beloved son of the U.S. president has succumbed to typhoid fever, leaving Lincoln utterly bereft at the very moment when his capacity to guide the nation through its darkest hour is most in doubt. This is the historical background against which George Saunders sets his first novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, a swirling kaleidoscope of voices from beyond the grave that at times inhabits the consciousness of Abraham Lincoln, who has come to his son’s crypt in the dead of night to see and touch him one last time.

Saunders has long been a “writer’s writer”—an idiosyncratic, whimsical, one-of-a-kind voice with a devoted cult of followers and imitators. He is frequently compared to Vonnegut in his madcap approach to satirizing the human condition, as well as a tendency to defy the conventions of traditional narrative. Formal hijinks aside, one can’t easily mimic the peculiar fusion of whimsy, yearning, and philosophical speculation for which Saunders has become rightly famous as a true original.

Saunders is also among a microscopic coterie of writers to achieve popular recognition solely on the basis of short stories. His most recent collection, Tenth of December, earned a slew of literary honors and also reached #2 on The New York Times bestseller list. As a result, enormous anticipation has buzzed around Lincoln in the Bardo. I am pleased to report that it is the best George Saunders novel I’ve ever read.

That’s not really a joke. Lincoln in the Bardo is a remarkable achievement; it’s also so unique in form and style that readers new to Saunders may feel a bit confounded. A collage of commentary from a dizzying array of voices, Lincoln in the Bardo is built around a stirring subject: Abraham Lincoln’s grief for his beloved son Willie at a time when Lincoln himself is tasked with navigating the nation through unprecedented turmoil. Perhaps the subject is too rife with pathos to go at directly. Dickinson’s famous lines from “Tell all the truth but tell it slant” come to mind: “The Truth must dazzle gradually / Or every man be blind.”

That’s not really a joke. Lincoln in the Bardo is a remarkable achievement; it’s also so unique in form and style that readers new to Saunders may feel a bit confounded. A collage of commentary from a dizzying array of voices, Lincoln in the Bardo is built around a stirring subject: Abraham Lincoln’s grief for his beloved son Willie at a time when Lincoln himself is tasked with navigating the nation through unprecedented turmoil. Perhaps the subject is too rife with pathos to go at directly. Dickinson’s famous lines from “Tell all the truth but tell it slant” come to mind: “The Truth must dazzle gradually / Or every man be blind.”

Hence, Saunders dispenses with anything resembling conventional narrative and approaches the heart of the matter through a peculiarly mystical concept. In Tibetan Buddhist tradition, the “Bardo” is the liminal state between death and reincarnation, a soul’s environment between lives. Through a phantasmagoria of ghostly voices, Saunders shows Lincoln attempting to commune with Willie, whom he called “too good for this earth.”

But the voices of the dead (including Willie Lincoln himself) are not meant to be a sideshow to the drama. They are the principle characters, and their own dramas and histories both before and after death are as essential to Lincoln in the Bardo as the title character, if not more so. Saunders’s experiments are situated firmly in the style of postmodern pastiche, in both senses of the term: a collage of voices and perspectives and an homage of sorts to the great poets and writers contemporaneous to Lincoln, along with at least one of their postbellum heirs, Edgar Lee Masters. Indeed, at times, Lincoln bears striking resemblance to Masters’s Spoon River Anthology, a collection of poetic epitaphs delivered in the voices of the departed citizens of Spoon River.

But there are also clear points of reference to the Orphic poems of Emily Dickinson, Whitman’s “Song of Myself” and his great elegy for Lincoln, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d,” and Melville’s Moby-Dick, which, like Lincoln in the Bardo, begins with a list of quotations or “extracts” some fifteen pages in length. The very concept of the Bardo calls to mind Emerson’s famous lines from “Nature”: “I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.”

Other, more far-reaching comparisons are equally apt. I’m thinking here of Dante or Hieronymus Bosch, for Saunders’s Bardo is no mere ghostly playground. Terrors abound; the dead are not safe from harm. There is also comedy, for, as one ghostly character bluntly explains, “it was dull here, and we craved the slightest variation.” The humor does not seem out of place for a text that embraces the full spectrum of emotions deriving from the experiences of death and grief.

Saunders seems to have selected his subject not for the purposes of examining history but because of Lincoln’s singular position as a man suffering the worst loss imaginable while already bearing the burden of thousands of deaths, knowing there will be many more to come: “He is just one,” he thinks. “And the weight of it is about to kill me.”

At times, Lincoln in the Bardo reads more like a play than a novel. Fittingly, the audiobook will feature a cast of some 164 readers that includes actors Ben Stiller, Julianne Moore, and Susan Sarandon; essayist David Sedaris; rockers Carrie Brownstein (of Portlandia and Sleater-Kinney fame) and Wilco frontman Jeff Tweedy; and Saunders himself. I recommend both formats simultaneously. Hearing skilled voices inhabit the characters will no doubt enhance the story’s resonance, but you’ll want to read along and hit the pause button to meditate on the novel’s finer aphorisms, like the following, which reads like a hybrid of epitaph and koan: “Love, love, I know what you are.”

Ed Tarkington’s debut novel, Only Love Can Break Your Heart, was published by Algonquin Books in January 2016. He lives in Nashville.