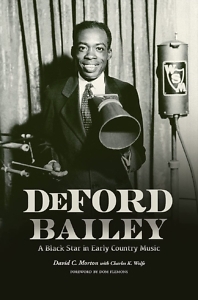

On a warm summer day in 1983, an unlikely mixture of family and friends, flanked by reporters and television crews, gathered one last time to pay tribute to a man who had once been a country music legend.

To some, DeFord Bailey was a name long forgotten, but not to those who came this day, who understood his character and talent — a life that was, as one of them put it, “a parable of integrity and survival.” In their recently rereleased 1991 biography, DeFord Bailey: A Black Star in Early Country Music, historians David C. Morton and Charles K. Wolfe described the cemetery scene this way:

To some, DeFord Bailey was a name long forgotten, but not to those who came this day, who understood his character and talent — a life that was, as one of them put it, “a parable of integrity and survival.” In their recently rereleased 1991 biography, DeFord Bailey: A Black Star in Early Country Music, historians David C. Morton and Charles K. Wolfe described the cemetery scene this way:

“One by one, the cars reached the main entrance and began to turn north… In front of them was a monument draped in white cloth; behind them were the old trees and gentle hills of the back part of the cemetery…. The grounds sloped down to the tracks of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad – appropriate, perhaps, given the love of railroads by the man they had come to honor.”

The people at the graveside, especially the musicians like Bill Monroe and Roy Acuff, all understood that DeFord Bailey found his musical inspiration everywhere — in the Methodist churches he attended as a child, in the “Black hillbilly” tunes of his once enslaved, fiddle-playing grandfather, but also in the lonesome sound of a passing locomotive.

In 1927, on a night the Grand Ole Opry got its name, Bailey opened the show with a train song, “Pan American Blues,” after radio announcer George D. Hay made the segue from NBC’s Music Appreciation Hour. The network show had ended that night with a symphonic composition inspired by a train, and Hay was only too happy to draw a comparison.

“For the past hour,” he said, “we have been listening to music largely from Grand Opera, but from now on, we will present The Grand Ole Opry.”

Bailey followed with his harmonica solo, “swooping in one phrase,” wrote Morton and Wolfe, “from a loud, braying trainlike phrase to a gentle, fluttering arpeggio.” Opry audiences were dazzled by his talent, and he quickly became one of the biggest stars in country music — “the Harmonica Wizard,” as Hay often put it.

In his graveside tribute, Acuff, who joined the Opry cast in 1938 and soon became known as “the King of Country Music,” remembered how in the early days he liked to perform with Bailey because he “could draw a crowd when nobody knew Roy Acuff.” He called for Bailey’s induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame.

“If his name is ever on the ballot,” Acuff said, “he’ll have one vote from Roy Acuff.”

In 2005, Bailey was, in fact, inducted into the hall of fame, the redemption of a musical legacy that David Morton had worked for more than 30 years to preserve. He first met Bailey in 1973, and the two of them became close friends. Morton was impressed by Bailey’s story — how this diminutive African American man, afflicted by polio as a child, had negotiated the terrain of Jim Crow to make music that crossed racial barriers.

As Bailey later put it, “The Black and the white all wanted to hear the same tune.”

For more than 15 years, Bailey was a legend. But then in 1941, he was abruptly fired from the Grand Ole Opry, caught in the curious crossfire of a corporate battle to license new songs. He was a stylist more than a composer, taking old tunes he learned as a boy, or those he liked by other artists, and creating renditions distinctively his own. He didn’t understand the sudden demand that he write new songs, which could then be licensed by BMI, a new enterprise supported by the Opry.

George Hay, adding an ugly dimension to the story, described the firing this way: “Like some members of his race and others, DeFord was lazy. He knew about a dozen numbers, which he put on the air and recorded for a major company, but he refused to learn any more, even though the reward was great. He was our mascot and is still loved by the entire company.”

For Bailey, the words cut deep. The personal insult and racial condescension were compounded by the fact that he had regarded Hay as a friend. He didn’t talk about it much. He simply picked up his life and moved on. He played his harmonica every day — it was his only addiction, he said — but he seldom performed in public any more. Instead, he made his living shining shoes.

But as Morton discovered, Bailey worried about how he might be remembered, fearful that history would misunderstand him.

“I promised him,” Morton said in an interview, “that I would mark his grave and tell his story.”

A definitive, well-crafted biography, first published in 1991, now rereleased with new material, was a major step in keeping that promise. As a collaborator, Morton turned to Charles Wolfe, a widely published English professor at Middle Tennessee State University, who had written extensively about country music.

But there was more to Morton’s commitment. In the later years of Bailey’s life, he also arranged for strategic interviews (including one I did for Country Music magazine) and occasional performances that he thought would raise his friend’s profile.

Under Morton’s prodding, Bailey made several appearances on the Opry, both at the Ryman Auditorium and the newer facility at Opryland. He also performed on Night Train, a radio show on Nashville’s WLAC aimed primarily at a Black audience, and was featured posthumously in Ken Burns’ PBS series, Country Music.

Bailey’s legacy has continued to grow. In 2022, Old Crow Medicine Show debuted a new song entitled “DeFord Bailey Rides Again.” And in 2023, Ketch Secor, the band’s lead singer, was among those who persuaded the Opry to apologize formally for Bailey’s firing.

For David Morton, there is now a symmetry to the story — “It’s incredibly satisfying,” he told me — and he and Wolfe end their book with Bailey’s own words:

“I want you to tell the world about this Black man. He ain’t no fool. Just let people know what I am … I take the bitter with the sweet. Every day is Sunday with me. I’m happy-go-lucky.

“Amen!”

Frye Gaillard, author of A Hard Rain: America in the 1960s and The Southernization of America, is writer-in-residence at the University of South Alabama.