A Refuge from the Noise of the World

The University of Tennessee’s Arthur Smith has built a life centered on poetry

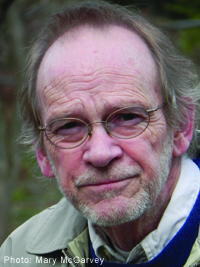

When I first met the poet Arthur Smith years ago, I was a sophomore taking his intro-to-poetry class at the University of Tennessee. I entered his class simultaneously insecure about and overconfident in my own poetic abilities, a combination that is somehow standard issue for the undergraduate artistic temperament. As we each flittered in, Smith continued to read behind his desk, reminding me of a thinner, more somber (if that’s possible) version of Robert Frost. Once class began, he became animated, reciting lines from memory as he made various points about a poem’s structure or syntax. And for every point he made, a young woman in the front row piped up with a contradictory opinion. We were all growing weary of her by class’s end, so when Smith asked if she had a minute after class, I suddenly discovered that my backpack needed reorganizing. “This is a class about poetry,” he told her quietly but firmly. “This is not a class about you and me talking.” In that moment, he simultaneously silenced the chatterer and established the position that guides his own life: poetry reigns.

Poets are not immune to the rush of contemporary life. Too often, writing—even for a respected poet—comes to seem like an afterthought, the work that gets done when all other obligations are finally taken care of. Arthur Smith is the rare writer who eschews the noise of the world, sculpting a life of quiet contemplation. Smith is also a poet who offers the kind of deep yet accessible poems that readers seek but so rarely find. His fourth collection, The Fortunate Era, will be released February 26 by his longtime publisher, Carnegie Mellon University Press. Its bold, honest, lyrical reflections offer a respite from the noise of the world.

Poets are not immune to the rush of contemporary life. Too often, writing—even for a respected poet—comes to seem like an afterthought, the work that gets done when all other obligations are finally taken care of. Arthur Smith is the rare writer who eschews the noise of the world, sculpting a life of quiet contemplation. Smith is also a poet who offers the kind of deep yet accessible poems that readers seek but so rarely find. His fourth collection, The Fortunate Era, will be released February 26 by his longtime publisher, Carnegie Mellon University Press. Its bold, honest, lyrical reflections offer a respite from the noise of the world.

Those of us who know Smith marvel at the habits that sustain his passion. For lunch every day, he has a bagel, a Twix, and a Coke Zero. He begins writing once everyone goes to bed and works until three in the morning. Late at night, he has more Twix and Zeros, plus cashews, cookies, and red Australian licorice—and then he tops it all off with either tapioca pudding or sorbetto. These routines would not suit most people, but they suit Art Smith.

Smith’s wife, Mary McGarvey, works in business planning and development at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. McGarvey has been an active wildlife volunteer for years, most recently at the large-cat sanctuary, Tiger Haven, in Roane County. Smith and McGarvey have four dogs of their own, and at one time they also kept a rescued raccoon in a cage that took up half their dining room. Simply put, both Smith and McGarvey build their lives around their passions and cut out the rest.

For Smith, it’s not a matter of subjecting his life to poetry: it’s a matter of finding in poetry the best way to understand his own life. He shares this quality with the poet Jack Gilbert, whose work is similar to Smith’s in its pared-down focus, quick developmental turns, and no-nonsense tone: “Not many people, let alone poets, are willing to make the sacrifices [Gilbert] made for his poetry and his life,” Smith says. “The poetry all along was meant to enable him to better understand his life and appreciate it more. And when you boil that process down, what does it come to but carpe diem, which is what poetry has always tried to gain.”

Smith’s own sense of the importance of seizing the day is no doubt informed by two crucial experiences in his twenties and early thirties: leaving his home state and losing his first wife to cancer. Born and raised in California, Smith received his first two degrees from San Francisco State University. He had just left California to attend the University of Houston’s prestigious Ph.D. program in creative writing when his wife, Veronica Keller, was diagnosed with an aggressive form of breast cancer. She died in 1981 when she was just thirty-one.

Smith’s own sense of the importance of seizing the day is no doubt informed by two crucial experiences in his twenties and early thirties: leaving his home state and losing his first wife to cancer. Born and raised in California, Smith received his first two degrees from San Francisco State University. He had just left California to attend the University of Houston’s prestigious Ph.D. program in creative writing when his wife, Veronica Keller, was diagnosed with an aggressive form of breast cancer. She died in 1981 when she was just thirty-one.

After taking a year’s leave of absence, Smith returned to Houston, where he continued to write. In 1985, his first book of poems, Elegy on Independence Day, was awarded the coveted Agnes Lynch Starrett Poetry Prize. That same year, Smith also received the Norma Farber First Book Award, a National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing Fellowship, and two Pushcart Prizes. His early poems were published in high-profile publications like The Nation and The New Yorker, all of which helped establish him as one of the nation’s finest poets.

Smith came to the University of Tennessee in 1986, quickly earning a reputation as a gifted and gentle mentor. Brad Tice, a former student with a book forthcoming from New Rivers Press this year, notes that Smith has spent hours reading his work. “What Art is really good at,” Tice says, “is identifying what the poem wants to do. He focuses on figuring out the poem’s conflict. So, if I am writing about a past experience, he always asks what current event triggered that memory. Nothing remains in isolation.”

Such concerns for the interconnectedness of past and present are reflected in Smith’s own work. Elegy on Independence Day centers on the loss of his wife and is “very personal, intense to me,” Smith said. The next book, Orders of Affection, has a greater outward focus, but his third book, The Late World, returns again to the interior. Smith believes his latest book, The Fortunate Era, is the most balanced: the poems reach outward toward the cosmos, history, and ultimately the churning pull of progression that insists upon destruction with every accomplishment.

The book’s title is taken from a comment by physicist Sheldon Glashow, who posited that protons will eventually decay. “We live in the fortunate era when matter is possible,” Smith explains, “so the book is a celebration of life.” Even in his poems about loss, grief is always balanced by an equal desire to survive such sadness. Consider these opening lines from the poem “What Gods”:

The new world has been

Tough on everyone—the young

Adrift, numb

On chatter, the old

Living out a golden age,

The rest of us aligned with liars….

This bleak opening is offset by the poem’s conclusion, which imagines the speaker’s mother continuing her own life despite so much that’s lost:

Over two thousand miles away

My mother growing elderly in the deserts

Of California, tending a little fire,

Watching over

What’s left of her husband

And daughter, something in the old woman

Deeper now, adamantine, not even needing the fire.

What now? it chuffs, puffing heat

Into her cupped hands. Where to?

One distinctive element in Smith’s work is an insistence on articulating what confounds or contradicts. Since the ancient Greeks, the lyric poem “questions itself,” Smith explains; the poem is a “a self-correcting mechanism.” Poet Marilyn Kallet, Smith’s colleague at UT, says that Smith’s own poetry “is a model of what lyric verse can be: language compressed but still sonorous, idiomatic and personal.”

Kallet sums up Smith’s work with a nod to the great poet William Carlos Williams, who famously wrote, “It is difficult / to get the news from poems / yet men die miserably every day / for lack / of what is found there.” Arthur Smith’s poetry, Kallet says, is “that ‘news’ we cannot live without.”