A Sinister Beauty

Madison Smartt Bell talks to Chapter 16 about his provocative new novel

The author of thirteen novels and two short story collections, Tennessee native Madison Smartt Bell has often explored grim territory in his work, ranging from the seamy world of petty criminals in Save Me, Joe Louis to the blood-soaked battlefields of the Civil War in Devil’s Dream. He is best known for a highly acclaimed trio of novels on the Haitian revolution, which were described by one New York Times reviewer as “full of dreams and horrors”—a phrase that could as easily describe his latest book, The Color of Night, due in April. The novel enters the mind of Mae, a woman who has channeled the incestuous abuse of her childhood into a mystical, eroticized obsession with violence and death. Televised images of the 9/11 attacks thrill her, spurring memories of a sojourn with a Manson-like cult and of a woman, Laurel, who was her lover and ally there. Mae’s quest to find Laurel leads her to Ground Zero and to a final, crystalline moment of violence. The novel is a nightmare of real-life bloodshed and Mae’s mythic fantasies, vividly conveyed in Bell’s silky prose.

With its provocative use of 9/11 imagery and a protagonist who confounds typical notions of victimized women, The Color of Night is bound to touch some nerves. In the book’s acknowledgments, Bell himself describes the novel as “the most vicious and appalling story ever to pass through my hand to the page.” He answered questions from Chapter 16 by email about the genesis of the book and the process of creating it.

Chapter 16: The Color of Night seems like a serious departure from the historical fiction you’ve concentrated on in recent years. Can you describe the genesis of the book? Has it been brewing for a long time?

Chapter 16: The Color of Night seems like a serious departure from the historical fiction you’ve concentrated on in recent years. Can you describe the genesis of the book? Has it been brewing for a long time?

Bell: Well, my first nine books of fiction were set in my own time. And when I got involved with the long Haitian historical project I always was writing something contemporary back to back with the Haitian novel in hand (Save Me, Joe Louis; Ten Indians; Anything Goes).

I started writing Color of Night while working on the Forrest book; it was a return to an idea I’d had a couple of years earlier, soon after I finished the last Haitian novel and didn’t really know what to do next. I did a couple nonfiction projects that were [each] part of [a] series at that time (Lavoisier, Charm City), and another series turned up which was hiring literary fiction writers to recast mythological stories. I proposed [a book on the] Manson girls as Maenads, though not exactly in those words. They turned it down. I didn’t have a lot invested in it at the time, just a 250 word pitch and a scrap of scene—really, just a whisper of the voice of the character who became Mae.

At that early stage I had imagined her as an ancient crone but when I came back to it I realized that she wouldn’t have to be all that old and if she was conceiving herself as immortal it wouldn’t really matter anyway.

Me, I was twelve, I think, when the Manson murders happened. I did a little research on that part of the story, enough to make me realize what a different time that was from the one we’re in now. There was a moment at the end of the 1960s when it really did look like society might collapse, implode, or transform itself beyond recognition.

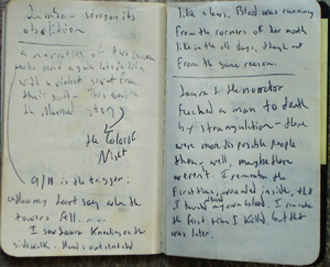

A publicist asked me if I had any handwritten material on the book, so I took some pictures of my shirt-pocket moleskins that were relevant. I’ll attach the one that shows when I first came back to the idea. The catalyst was connecting the sixties events to 9-11 and the idea that someone who saw herself as a maenad would rejoice in the fall of the towers.

A publicist asked me if I had any handwritten material on the book, so I took some pictures of my shirt-pocket moleskins that were relevant. I’ll attach the one that shows when I first came back to the idea. The catalyst was connecting the sixties events to 9-11 and the idea that someone who saw herself as a maenad would rejoice in the fall of the towers.

Another kind of peculiar ingredient—I think this book draws some of its feel from Neil Gaiman’s Sandman series. I read these books only when I have a high fever, so that plays into it too.

Chapter 16: Is the creative process different for a novel like The Color of Night, as opposed to one grounded in history, such as

Bell: Well, yeah, any contemporary project is like taking off the ankle weights compared to writing historical fiction, where I typically have to pull out four or five sources to construct every scene. The Color of Night, however, is about the easiest thing I have ever written. Partly because the episodes are so short, I reckon. I had always wanted to do something in the pared-down style of Joan Didion’s Play It As It Lays, and this is it.

I’ve always taken inspiration quite literally. (Exploration of Haitan culture clarified that for me.) To be possessed by the story being told is a good situation for the writer. And this book was more like that in the composition than anything else I have done, apart from a couple of short stories. I wrote most of it direct to the keyboard with next to no revision. Having something like that pass through gives a strong catharsis, and in this case it was so strong I was scarcely aware of how sinister the content was.

Chapter 16: The book’s epigraph, from Iris Murdoch’s The Unicorn, concerns the concept of Ate. Can you explain your own understanding of Ate and how it relates to Mae’s story? Did you think of the book as an allegory when you were writing it?

Bell: I read a lot of Iris Murdoch when I was in my late teens. One of her weird and wonderful gifts was to make recondite ideas seem sexy—or maybe it’s better to say [she revealed] that in fact they are sexy. And I think some of the feel of the Murdoch novels leaks into this one of mine, without my being aware of it until, in the midst of writing this book, I happened to pick up The Unicorn and through serendipity, synchronicity, struck the passage that I used for an epigraph. I’ve not found Ate interpreted anywhere else in quite this way. Murdoch’s take is rather special—and for my purposes, or Mae’s purposes, works perfectly. Mythological Ate is a spirit of blind folly, delusion, rash action, cast down from Olympus. Aeschylus (this is a second-hand report here) assimilates Ate to the Fates and the Furies, which would tend to inject her destructiveness with meaning, and my guess would be that Murdoch’s read draws on Aeschylus to some extent, but it has been a Long Time since I have read Aeschylus, though I did read the Bacchae for background.

Mae’s doing the thinking in this book. I merely take dictation from her. And she does conceive the story in an allegorical way; that is, her understanding of the events of her own life is an allegory which she takes literally.

Mae’s doing the thinking in this book. I merely take dictation from her. And she does conceive the story in an allegorical way; that is, her understanding of the events of her own life is an allegory which she takes literally.

Chapter 16: It’s fair to say that Mae confounds conventional notions about what sexual violence does to women. Maybe she confounds conventional notions about women, period. Did you have that in mind as you created her?

Bell: I don’t think I want to start generalizing about women and sexual violence at all. I’m no expert. By and large I find women difficult to write; I try conscientiously and feel that all I ever achieve is an impression of conscientious trying. And yet Mae was written so easily, it’s like she wrote herself.

Mae’s a special case of someone who’s said to herself, whatever doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. My idea is the book can be read on two levels. The mundane interpretation is that Mae’s idea that she has been immortalized by her suffering is simply a coping mechanism (which is what Laurel seems to believe, at the end). Or the reader can take Mae at her word. Since the reader is so deep in Mae’s consciousness all the time, gravity pulls in that direction. In her view she is not a mortal woman but a goddess, so the characteristics of mortal women are not to be applied to her—and the reader is experiencing a myth about this goddess, not some other kind of narrative.

Chapter 16: In the acknowledgments for The Color of Night, you concede that “inevitably” some readers will hate it. Did you ever think about just putting it in a drawer for a while, or taming it in some way?

Bell: If you have your protagonist exulting in the fall of the World Trade Center on page one, you can count on upsetting a few people, and considering that all New York publishing takes place within a mile or so of the site, certain difficulties become very predictable. The effect loses intensity the further one gets from Ground Zero, and in fact I sold the book in France before I could place it in the U.S. though the U.S. edition will appear first.

I felt when I finished it that the book had a sort of unbreakable integrity, so I could never have watered it down. It is what it is, and I can’t do anything about it. I hardly even understand why I like it. The beauty of it is a terrible, sinister beauty, like that of a snake (my image) or a cat with a mouse (my agent’s image). Whatever else you might say about Mae, she has accomplished a perfect self-realization, placing herself “beyond good and evil,” in maybe a pre-Nietszchean way. There’s a purity in her that I admire, in the way she acts according to her nature.

Chapter 16: In interviews you’ve mentioned a work in progress called Red Stick, about the nineteenth-century Creek wars. Where does that project stand? Any other new projects, literary or otherwise, you’re willing to describe?

Bell: Red Stick will be my next book, Lord willing. It is almost two-thirds done and has got Tennessee all over it, since half of it’s in the point of view of Andrew Jackson. I’m thinking about doing a novel about the first Seminole war, which is the third act of Jackson’s campaign from Tennessee through Creek Country and New Orleans to the Atlantic coast of Florida. I’m also considering a novel set in the Reconstruction period after our Civil War, a novel about the Métis Rebellion in Rivière Rouge, and a zombi novel (based on real zombi, not the spawn of George Romero).

Chapter 16: Everyone seems to agree that these are dark days for publishing and bookselling, but can you see anything in the fallout that might wind up being good for authors? Given that there’s no turning back the clock, how would you like to see the changes play out?

Bell: Well, the printed book made a cultural revolution that has lasted for centuries, but it may actually be coming to an end. I’m not sure how significant these new electronic ways of distributing and consuming books (Kindle, iPad, etc) will be in the long run, though it is interesting to see them now catching on, after a quite a long while of not catching on. I think people will always need to tell themselves stories, but how they are going to do that may really be on the cusp of a radical change. What’s most troubling to me in all these changes is how many aspiring writers don’t read.

To read an excerpt from The Color of Night, click here.

31 January 2013 update: Madison Smartt Bell will give a free public reading tonight in Furman Hall, Room 114, on the campus of Vanderbilt University in Nashville. Click here for event details.