A Spirit That Passes Through

Novelist Madison Smartt Bell talks with Chapter 16 about the art and artists of Haiti

Nashville native Madison Smartt Bell is the author of three celebrated novels about the Haitian revolution, as well as a biography of Toussaint Louverture, but his connection to Haiti extends far beyond a writer’s intellectual interest. He has spent considerable time in the country, getting to know Haitians and their unique, deeply spiritual culture. In the wake of the devastating earthquake last January, Bell became a prominent advocate for Haiti, excoriating Pat Robertson at The Huffington Post and appearing on major news outlets to explain the many reasons that Haiti should not be defined by that disheartening label, “poorest country in the Western Hemisphere.”

The vibrant folk art of Haiti is one of its cultural treasures, and since the late 1990s Bell has been aiding a number of struggling painters by bringing their work to the U.S. In response to the urgent need created by the earthquake, Nashville’s LeQuire Gallery began selling the paintings in March, with proceeds to go to the artists and to Haitian-run aid organizations. Bell, a professor of English at Goucher College in Baltimore, will give a talk at the gallery on April 15, offering insights about the art and the current situation in Haiti. He answered questions from Chapter 16 by email in anticipation of his visit.

Chapter 16: Did you have a strong interest in Haitian art before you first visited the country in 1995? How did you wind up becoming a pro bono agent for painters?

Bell: No, I didn’t really know anything about it. When I first went to Haiti I knew lots about the period between 1791 and 1804 and practically nothing else. In Cap Haïtien in 1995 I met an artist named Guidel Présumé in the bar of the Mont Joli hotel. We hit it off immediately and he helped me do things and go places for my research (for the Haitian-based novels) that I would have had a hard time doing without him. He’d done very well as a painter up until the late 1990s, but at that time the tourist trade really began to dry up, because of persistent instability in Haiti (or at least the perception that Haiti was unstable, which was often false, in my experience).

Bell: No, I didn’t really know anything about it. When I first went to Haiti I knew lots about the period between 1791 and 1804 and practically nothing else. In Cap Haïtien in 1995 I met an artist named Guidel Présumé in the bar of the Mont Joli hotel. We hit it off immediately and he helped me do things and go places for my research (for the Haitian-based novels) that I would have had a hard time doing without him. He’d done very well as a painter up until the late 1990s, but at that time the tourist trade really began to dry up, because of persistent instability in Haiti (or at least the perception that Haiti was unstable, which was often false, in my experience).

I began trying to sell Présumé’s paintings in the U.S. to help him out a little, and gradually began doing the same for other artists he knew, many of them members of a cooperative in Cap H. called AJAPCA. I developed a system where I’d buy small paintings for what they would bring in Haiti and then try to resell [them] in the U.S. If I succeeded I would remit the entire difference to the artist on my next visit. I took all my profits in good will.

Chapter 16: Have you been in touch with any of the artists since the earthquake?

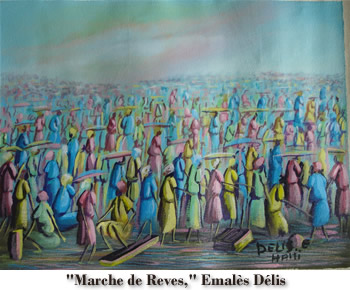

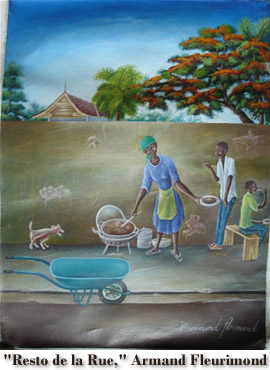

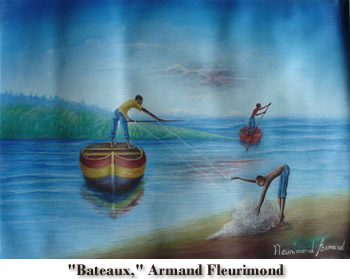

Bell: Yes. The AJAPCA group scattered around 2000, when they lost the studio/gallery space they’d had in Cap H. So I had lost touch with most of them long before the earthquake. Some went to the Dominican Republic, where there is tourism, and some to Port-au-Prince. Cap Haïtien was not much affected (directly) by the earthquake. So Présumé and others who remained there were all right. There were two painters I was still in touch with, Emalès Délis and Armand Fleurimond, who were in the capital for the earthquake and were not heard from for quite some time afterward. I had begun to give up on them, but eventually they both did reappear. They had spent several weeks living among the throngs of other survivors in open spaces of the capital. Fleurimond and his wife and child eventually made their way back to Cap [Haïtien]. There is work by both of these painters in the LeQuire Gallery show.

Chapter 16: Prior to the earthquake, were the artists in the LeQuire show—and others like them—able to make a living from their work?

Chapter 16: Prior to the earthquake, were the artists in the LeQuire show—and others like them—able to make a living from their work?

Bell: Doubtful. I mainly deal with artists from the Cap-Haïtien area, and though that used to be a big tourist destination, the tourist trade has not come back from the turmoil of the late 80s and early 90s, unfortunately. So, not enough customers on the ground. Painters in Port-au-Prince can do better, but then there are more of them there struggling for notice, too.

Chapter 16: Many of the paintings have Vodou themes. Do the artists think of those works as spiritual expressions, divinely inspired—or is their attitude toward their art more detached than that?

Bell: Depends on the artist and the particular work. Protestant artists, for example, would paint Vodou scenes simply as local color, if they paint them at all. And there is a lot of craft intention in this work; that is, most of it is less about self expression and more about making an object that someone will find desirable to buy. An exception in the LeQuire Gallery show is the work of Armand Fleurimond, which tends to have an autobiographical strain in it.

Many of the artists I deal with paint in several different styles, just as a matter [of] versatility in making a product, and it also seems to me that the same painters paint with vastly different degrees of what we call “inspiration,” as seen in the quality of the finished work. I think the process may be analogous to what happens in Vodou. A spirit comes along, dislodges the ego from the head of the painter, uses the painter’s hands to paint one or more paintings, sails on…. Later another spirit comes, maybe. See how different this is from our idea of self-expression in art?

There are cases in which artists who are also houngans or bokors make art objects which double as pwen. A pwen is a spirit power bound up in an object. They can be made to do magical work for their owners, etc. I have learned not to trade in this kind of artifact. The spirit trapped in a pwen is in slavery basically, so these things will turn on their masters.

There are cases in which artists who are also houngans or bokors make art objects which double as pwen. A pwen is a spirit power bound up in an object. They can be made to do magical work for their owners, etc. I have learned not to trade in this kind of artifact. The spirit trapped in a pwen is in slavery basically, so these things will turn on their masters.

Chapter 16: In a Washington Post article in 1996, you wrote, “[A]t the root level of Haitian society, among the paysans who form the vast majority of the population, the unconscious is not internal but external.” Can you elaborate a little on that idea, on how it is reflected in Haitian art?

Bell: Well, we can understand the entity called Les Morts et Les Mystères, or Ginen Anba Dlo, or Sa Nou Pa We Yo, as Vodouisants do, by saying that all three phrases identify the pool of spiritual energy of everyone who has ever died in Haiti. It’s from that reservoir that the particular personalized spirits or lwa emerge. Or we can psychologize it and say that these phrases identify something like the collective unconscious projected by First World depth psychology and psychoanalysis—a collective unconscious which in the case of Haitian culture is external and shared. That sharing is what makes magical thinking work much better in Haiti than in most other places. And it works out the same whatever you want to call it. In the case of artistic inspiration, among Haitians it’s more likely to come from outside and in—from a spirit that passes through and then moves on.

Chapter 16: Your encounter with Haiti has had a deep effect on you personally—for example, you’ve written about your experience with spirit possession and your practice of Vodou rituals. How has it changed you as a writer? Has it caused you to pursue your work in a different way?

Bell: I have always felt, as a lot of writers do, that I am more of a conduit than a creator in the material I write. Andrew Lytle, who was a good friend and wise advisor, put it this way: “You put yourself apart from yourself, and you enter the imaginary world.” It’s a description of entering a mild trance state. I am convinced that everyone who produces artifacts from the imagination uses some sort of trance experience to do it, though not everyone would be aware of it. In Haitian culture this sort of thing is highly systematized. The yourself-apart-from-yourself transition is sometimes called marassa (twins) and it’s often a prelude to full-blown possession. Most First World artists and writers don’t follow it quite that far. We’re generally too egotistical for that, and yet most do experience at least some degree of catharsis from the work.

Chapter 16: You’ve encouraged people to direct donations to grassroots Haitian organizations such as Fonkoze and the Lambi Fund of Haiti. Why do you think that’s a particularly effective way to help?

Chapter 16: You’ve encouraged people to direct donations to grassroots Haitian organizations such as Fonkoze and the Lambi Fund of Haiti. Why do you think that’s a particularly effective way to help?

Bell: These organizations are founded and run by Haitians and they have been operating in Haiti for a long time. They also are politics-proof, impervious to changes of government, which is quite important there. They spend comparatively little money on their own operational costs (unlike big international organizations, e.g. Red Cross) so donors can feel that money given to these two will go where it’s most needed. Both these organizations do a lot of different good things. But Fonkoze emphasizes microcredit and low-cost money transfer and banking, while Lambi emphasizes durable development projects, mostly agricultural. Partners in Health, which is Paul Farmer’s fund-raising vehicle, is also a good one—the best for health issues.

Chapter 16: The earthquake has inspired a global desire to help Haiti, beyond just giving immediate aid during this crisis. That’s obviously a good thing, but what are the possible dangers? Are there elements of Haitian culture that might be threatened by the invasion of outside interests and influences?

Bell: Though a lot smaller than China, Haiti has weird ability to absorb whatever comes into it and make it Haitian, whatever it is.

That said, there has been a struggle for a long time between the powers of globalization and Haitian culture. The latter depends a lot on local autonomy and local self-sufficiency. In the early 1990s Aristide set out to make Haiti agriculturally self-sufficient, which was a perfectly possible project then and might still be possible, if Haiti could get a few of its other problems solved. Globalization, however, wants Haiti to import U.S. agricultural surplus and export products from assembly plants (paying the lowest wages in the Western Hemisphere). This conflict of interest was the motive for international collusion in Aristide’s first overthrow. It’s not going away.

Also “we” are always eager to impose this thing we call “democracy” on countries like Haiti, and that’s probably better than the dictatorships they get otherwise. But how well are we doing with that ourselves, lately?

Madison Smartt Bell will speak at LeQuire Gallery in Nashville on Thursday, April 15. The event runs 6-7:30 p.m., with comments to begin at 6:30. The art will be on display through April 24.