A Stranger Comes to Town

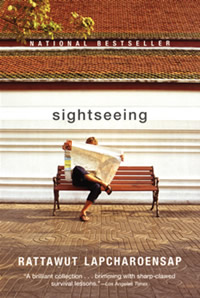

In Sightseeing, Rattawut Lapcharoensap explores the tension between tourists and locals

“Pussy and elephants. That’s all these people want,” a mother bitterly tells her son in “Farangs,” the opening story in Rattawut Lapcharoensap’s debut collection, Sightseeing. The stories, set in modern Thailand, offer keen glimpses of the country’s pressure points: the sites of tension between tourists and natives, citizens and government, and within families. The narrator of “Farangs” is the son of an American sergeant, long vanished, and a Thai mother who is dismayed to find her son drawn to the Western girls who check into the small beachfront motel that he helps his mother run.

Lapcharoensap turns an eye to the seamier side of Bangkok and Thai outposts, but his characters are often innocents, gentle spirits who are keenly aware of the pain of the world that surrounds them. In “At the Café Lovely,” an eleven-year-old boy longs to bond with his older brother Anek; their father is dead, and their mother is lost to them in the aftermath of her own loss. When Anek finally agrees to take him out on the town one night, the boy’s naive vision of his more-worldly brother is shattered: their destination is a whorehouse masquerading as a bar where Anek and his friends get high on paint thinner.

Published in 2005, Sightseeing set the bar high for Lapcharoensap. The collection got him named to the National Book Award’s “5 Under 35” list and won the Asian American Literary Award; it also made the shortlist for the Guardian First Book Award. In a review in the Guardian, William Sutcliffe lavished it with praise: Lapcharoensap, he wrote, “finds moments of beauty in otherwise bleak settings. This collection is intensely political and profoundly angry about the corrupt, poverty-stricken condition of Thailand, yet every story is primarily driven by a warmth and a belief in humanity that allows for unexpectedly uplifting and touching moments. That he achieves this without ever straying into kitsch is astonishing.” Sutcliffe pronounced Sightseeing’s seven stories possessed of “a truly novelistic richness.”

Indeed, a few years later, Lapcharoensap, who was born in Chicago and raised in Thailand, was named a Best Young American Novelist by Granta magazine—without a published novel to his name. A Whiting Award—given to writers who show exceptional promise early in their career—followed in 2010. Lapcharoensap currently teaches in the Creative Writing M.F.A. program at the University of Wyoming. He answered questions from Chapter 16 via email in advance of his reading at Vanderbilt University in Nashville on October 20.

Indeed, a few years later, Lapcharoensap, who was born in Chicago and raised in Thailand, was named a Best Young American Novelist by Granta magazine—without a published novel to his name. A Whiting Award—given to writers who show exceptional promise early in their career—followed in 2010. Lapcharoensap currently teaches in the Creative Writing M.F.A. program at the University of Wyoming. He answered questions from Chapter 16 via email in advance of his reading at Vanderbilt University in Nashville on October 20.

Chapter 16: Several of the stories in your collection feature sons and mothers; fathers are absent from the picture. Was this the result of a conscious artistic decision? Looking back now—especially as a new father yourself—do you read them differently at all?

Lapcharoensap: It wasn’t a conscious decision at all. Nevertheless, conscious or not, I have a sneaking suspicion that my own upbringing as a child of a single mother must surely have had something to do with the dearth of fathers in the collection. This is not to say that the stories are directly autobiographical in any way; it’s only to say that that so-called “gap” or “absence” certainly feels very familiar to me.

Chapter 16: You were raised in Bangkok. What made you decide to return to the States to earn an M.F.A., and how did that experience compare with your expectations for it?

Lapcharoensap: I moved back to the U.S. to pursue my B.A. I somehow never left. I certainly never had designs on an M.F.A in creative writing when I first arrived. I’d never really even heard of such a thing until late in my undergraduate career, when I had the outrageous good fortune of receiving the encouragement of several wonderful writing teachers at Cornell University: Michael Koch, Stephanie Vaughn, and Helena Viramontes. They sent me on my way.

Chapter 16: Several stories in Sightseeing probe the sometimes-uneasy relationships between tourists and natives in Thailand; in the title story, the main characters—a boy and his mother, who is going blind—are both at once. What do you find intriguing about this theme? Are you still exploring it in your new work?

Lapcharoensap: “The stranger comes to town” always presents an interesting narrative situation, I think, and with tourism what you basically have is a narrative wherein the stranger comes to town to relax and have a vacation and generally indulge in leisure activities, away from the nine-to-five exigencies of the labor market back home, while the so-called native population remains very much mired in their own labor market, trying to earn a living from the stranger’s leisure and fun. The boundary between the two couldn’t be clearer, the anxieties on both sides couldn’t be more awkward and unsettling, and in a deeply entrenched tourist economy like Thailand’s both parties tend to have to spend a lot of time with each other, often against their will. When I wrote the stories in Sightseeing, these kinds of tensions felt dramatically promising.

Lapcharoensap: “The stranger comes to town” always presents an interesting narrative situation, I think, and with tourism what you basically have is a narrative wherein the stranger comes to town to relax and have a vacation and generally indulge in leisure activities, away from the nine-to-five exigencies of the labor market back home, while the so-called native population remains very much mired in their own labor market, trying to earn a living from the stranger’s leisure and fun. The boundary between the two couldn’t be clearer, the anxieties on both sides couldn’t be more awkward and unsettling, and in a deeply entrenched tourist economy like Thailand’s both parties tend to have to spend a lot of time with each other, often against their will. When I wrote the stories in Sightseeing, these kinds of tensions felt dramatically promising.

All that said, my new work has very little to do with tourism at all.

Chapter 16: What is your new work about? Is it a novel?

Lapcharoensap: I’m currently working on a novel set primarily in post-WWII Bangkok, a portrait of one woman’s life during that particular time, a daughter of Chinese immigrants.

Chapter 16: Has being lauded as a “best American novelist” before you’ve even written a novel upped the first-novel anxiety factor at all?

Lapcharoensap: In a way, certainly, yes. It’s always wonderful to be publicly recognized for one’s work, though a little strange to be recognized for something one’s never successfully done. I worked for years on two novels whose narrative and structural problems were apparent to everybody but myself. I’m not even the best novelist on my block, here in Laramie, Wyoming. But when it’s going well, you just sit down and do it, and nothing else seems to really matter. If you’re lucky you enter a state of un-distractibility. All that other stuff just kind of disappears, if you can help it. Or at least that’s the idea.

Chapter 16: Do you think of yourself as a Thai writer or an American writer? Or neither? Do such titles matter?

Lapcharoensap: I tend to think of myself as a writer of English-language prose, primarily. I also tend to imagine myself as both “Thai” and “American,” when I need to imagine myself in such terms at all. It’s not really a choice, I don’t think, and certainly not a mutually exclusive one. But, at the end of the day, no, such “titles” hardly matter. The writing matters, yes. But not the writer. At a certain point I don’t really care about who Anton Chekhov or Katharine Anne Porter or Samuel Beckett are, where they’re from; I only care about what they do, what they did, in their work.

Rattawut Lapcharoensap will read from his work at Vanderbilt University in Nashville on October 20 at 7 p.m. in Buttrick Hall, Room 101. The event is free and open to the public.