A Word’s Weight

A writer once called his Sunday School teacher the worst name he could think of—and it haunts him still

In 1957, when I was eight years old, I called my Sunday School teacher, Miss Jeffie Lou Beecroft, a bad word. I didn’t call her the bad word to her face, but it was a very bad word, apparently the worst word I had in me at the time, and that’s what has mattered ever since.

I only vaguely remember the precipitating event. I think I had leaned forward slightly and whispered something to a girl I wanted to impress. Miss Jeffie—who belonged to the Memphis Storytellers’ League and was famous for her ability to bring Bible stories to life—stopped the day’s vivid account mid-sentence, paused dramatically, and in a soft voice that managed to be both martyred and forceful, said: “When Chip is all finished talking, we’ll go on with our story.”

I only vaguely remember the precipitating event. I think I had leaned forward slightly and whispered something to a girl I wanted to impress. Miss Jeffie—who belonged to the Memphis Storytellers’ League and was famous for her ability to bring Bible stories to life—stopped the day’s vivid account mid-sentence, paused dramatically, and in a soft voice that managed to be both martyred and forceful, said: “When Chip is all finished talking, we’ll go on with our story.”

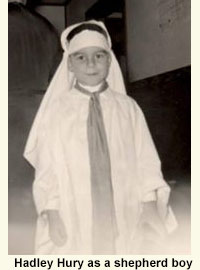

Not exactly a public laceration, but for me it was devastating. I was a good boy. I tried always to do the right thing. Everyone thought I had been a particularly watchful and adoring shepherd in the kindergarten nativity enactment. For four years I had brought home perfect conduct grades from my elementary school. I was a Cub Scout. Like the 1950s families we all saw reflected on TV—that Ozzie & Harriet, Leave It to Beaver, Father Knows Best world of conformity—my family was a model of decorum. My parents were active in the church, but they were neither dour nor sanctimonious. They dressed well and played bridge with the other parents. We had a Buick Roadmaster. On the bookish and introverted side, I had learned how to use language for social salvation: though I was consistently my teachers’ pet, I also enjoyed helping my classmates with their work, and I could make people laugh. And adults seemed to trust me.

But in that Sunday School classroom, with one sentence, my world suddenly collapsed. One minute I was in my place, the place I knew—a large, sunny second-floor room with three or four carefully ordered rows of small wooden chairs and Miss Jeffie’s desk off to one side, holding a vase of flowers from her garden. The next minute a dark and dreadful curtain, like a plague of locusts, crossed my field of vision. I managed to straighten myself in my chair, though I did not know what I was doing, could feel nothing. I was mortified.

Miss Jeffie continued the animated narrative with her usual theatrical gestures, widened eyes, modulated volume and tone. No one seemed to register the rupture that I felt like an open wound. Before too long, we were singing “Climb, Climb Up Sunshine Mountain” and then filing out the door for the fifteen-minute break before the church service. I’ll never know if Miss Jeffie made some move to intercept me for a possibly ameliorating word in private—I stayed within a group, my head down, and got out the door as quickly as possible.

By the time church was out an hour later, word had spread. I remember trying to will myself into invisibility as I stood on the walkway, nearly incontinent, waiting for my parents to come along and nudge my sister and me to the car.

During that fifteen-minute break is when it happened.

I was standing downstairs with a few boys from the class, sipping Cokes from the machine that stood on a landing near a side entrance. No one mentioned anything; no one seemed to care. No one seemed to care, that is, until Donnie Crupp, relentlessly true to form, spoke with a derisive snort, “She really got on you.” As he said it, he looked around at the others; after he said it, he laughed with a perfectly calculated ambivalence, indicating that we were all laughing at her, yet making sure that I was implicated, too—making it clear that I had lost face.

I have no idea where it came from, but I called Miss Jeffie the worst word I could think of, the most disdainful epithet any intelligent, well-brought-up white boy could say about the nice white lady who was his Sunday School teacher, and I didn’t so much say it, as unleash it: “She’s a nigger!”

By the time church was out an hour later, word had spread. I remember trying to will myself into invisibility as I stood on the walkway, nearly incontinent, waiting for my parents to come along and nudge my sister and me to the car. But the nightmare unfolded, and there was Miss Jeffie zigzagging toward me through the crowd, bright-eyed and zealous. She firmly took my upper arm and leaned in, inches from my face, to whisper, “Thank you for calling me a nigger.”

Precisely when and how my parents learned of my fall I never knew. Punishment ensued. A mere swat on the bottom was insufficient for a transgression of this magnitude, and I was not yet of an age to be grounded. I remember the ongoing shock waves leading up to, including, and following the extraordinarily serious “How could you?” talk. I had done the worst thing possible: I had disappointed them. My mother was a lovely woman, but when I disappointed my parents, her face became a stricken mask, etched with pain. In this dire situation, the compression of her lips may have been etched even more firmly.

Only with the passage of years have I come to understand what really happened after that Sunday School lesson in 1957. As far as my parents or any of their church friends were concerned, what I said was wrong not because it was despicable but because it was common. The problem with the word that leapt from my mouth was neither the animus behind it nor its terrible freight of meaning, but rather that it was not used in polite society, not used by people like us.

Bad words have come and gone in these intervening years. I’m sure I have been on the receiving end of a few. More often I have heard them hissed about or hurled toward others, but even then I have felt a certain complicity.

The lesson from my parents and Miss Jeffie was clear: language was to be as rigorously maintained as any seating arrangement in a city bus or dimestore lunch counter. No one heard horror in that word; no one recognized an overripe moment for teaching and learning. What they heard was simply a social solecism, a boy’s impertinent rudeness. Hard truths may have been afoot, but they were not yet admitted through the front door. In retrospect, and not merely because I would like it to be true, I sense that my parents—good people, kind people—would like to have said something more but did not yet have the right words.

During the 1960s my church, as it happened, was one of the few in the city that welcomed black people to its worship services. But on that Sunday in 1957, I had heard only fragmentary asides about Little Rock and “integration.” On that day, all those anxious undercurrents and uncertainties conflated with my own delicate hold on identity. The world as I knew it, and insofar as I could trust it, was spinning out of control. Chaos threatened. I felt utterly powerless.

Before too much time passed, the episode was forgotten, or perhaps it was buried. I finished high school and started college in the next tempestuous era. I became active in the cause for civil rights. I marched, I voted, I joined. For the first time I began to count African Americans among my friends.

But I can never get over the bright October Sunday that suddenly went dim because of a word I said. The bright October Sunday when, as I once heard a black friend’s grandmother refer to it, I called Miss Jeffie “out of her name.”

With expanded forms of media, the name-calling today has proliferated, becoming even more vitriolic. Other bad words have come and gone in these intervening years. I’m sure I have been on the receiving end of a few. More often I have heard them hissed about or hurled toward others, but even then I have felt a certain complicity. We have lived to see a sitting president of the United States publicly reviled—not because of his policies but because of a scarcely veiled, visceral revulsion against the color of his skin. This is disturbing not only because he is a compassionate, strong, intelligent human being but because words of such vitriol are now that much more difficult to retrieve, much less atone for or transmute. They can fester for decades in the civic body and in the individual soul.

That crisp blue Sunday morning in October was probably the beginning of the end of my childhood. It most certainly was a nail in the coffin of my innocence. And for a child who loved words, it was—for many, many years—a betrayal of my trust in the carefulness, the exactitude, the redemptive power of language.

I missed the widespread use of “Commie” by a couple of years, but over time there would be other epithets intended to wound: “Dyke! Faggot! Redneck! Terrorist!” Though each specific word matters crucially and means something specific, it’s clear that those voicing these invectives often don’t even know what they mean. The hatred behind them stems from a fear of having no agency, and they are goaded into voice by the Donnie Crupps of the world.

But what really brings the bitterness to my throat—a lifelong Sunday-morning sadness—is that I know, more or less, where the words are coming from.

Hadley Hury’s poetry has appeared in The Colorado Review, Image, Appalachian Heritage, Forge, Green Mountains Review, Off the Coast, and other journals. A Memphis native, he lives in Louisville and serves as Film Editor for Lost Coast Review in Newport Beach, California.