A Writer’s Words

A newspaperman recalls an unexpected afternoon with legendary author Shelby Foote

Every week, when the Chapter 16 newsletter lands in my inbox, I’m always pleased to see familiar friends—In the Miro District and Summons to Memphis by Peter Taylor; Three Novels by Shelby Foote—on the bookshelf at the top of the page.

No one wrote about Memphis like Peter Taylor. The opening paragraph of his short story, “Daphne’s Lover,” thrills me each time I read it:

When my friend Frank Lacy and I were thirteen and still wearing bell-bottomed sailor pants, he and I sat together one afternoon on the cement steps that led up to his house on Central Avenue. We were perched about midway on the wide flight, guarded on either side by a larger-than-life cement lion, couchant and cast in a rather more pebbly mixture than the steps were. Suddenly, in a voice that ranged up and down the scale, Frank burst out with: “Ah, Vinton! Ah, Goodbar! Ah, Harbert!” These were the names of streets in the old-fashioned Annandale section of Memphis where my family lived, only a few blocks from the fashionable Central Avenue section. “What noble old streets! What noble-sounding names!” said Frank. He was half joking, of course. Yet for Frank there was a mysterious aura about my neighborhood….

I grew up on those streets. They figure prominently in my novel, Paperboy:

In the part of Memphis where I live all the street names are sunk in the concrete on every corner in nice blue tile. I know all the streets but I like to read the name in my head each time I come to one. Vinton. Harbert. Carr. Melrose. Goodbar. Peabody. The streets are like friends that I don’t have to talk to.

And I can’t think about Memphis without thinking about the afternoon I ran into Shelby Foote.

My wife and I were living in a small house in the 2200 block of Monroe near East Parkway in the late 1970s. Going to work at 4 a.m. every day at the Memphis Press-Scimitar put me home about 1 in the afternoon. Occasionally I would take walks in the afternoon so I wouldn’t be napping when Betty got home from work.

One of my paths would take me by the big houses on East Parkway where Shelby Foote lived. This was before he became a household name in the early ‘90s thanks to the Ken Burns Civil War documentary on PBS. I was walking past Foote’s house, hidden by large pin oak trees, when I heard a lawnmower in the process of being cranked. Next came a series of curse words in an elegant Southern drawl that made swearing sound almost patrician. I recognized Foote as he came around the corner pushing his un-started mower toward the garage. I learned later, watching Ken Burns’s interviews, that Foote’s writing room was above that garage.

“Having trouble?” I asked. It was not like me to start an impromptu conversation, but seeing the famous writer had inspired me.

“Won’t start,” he said. “And I don’t know much about these infernal contraptions.”

“Mind if I have a look?”

“Help yourself,” he said.

I checked to see if it had gasoline. It did. I tried to crank it a few times, and it didn’t seem to be getting a spark. “Do you have anything I could take out the spark plug with?”

Without saying anything, he went to the garage and came back with a pair of pliers. You should never try to remove a spark plug with pliers, but I didn’t have the courage to tell him that. I pulled out a handkerchief, wrapped it around the ceramic part of the plug and began to work at removing it.

“My yard man has found himself incarcerated again,” Foote said. “I never have much luck trying to start these things.”

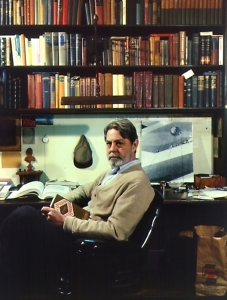

Infernal contraptions. Incarcerated. These were writers’ words, and only Foote’s molasses-like delivery could do them justice. He fired up his long-stemmed pipe and sat on a low brick wall at the side of the garage. His fingers were stained with ink. I also later learned that he did most of his writing with a dipped pin.

I finally removed the plug, whose tip was soaked with oil and gasoline. I cleaned it with the remnants of my handkerchief. “Let’s see if we can get a spark now,” I said. I put the spark-plug wire on the plug and held the tip of the plug next to the metal mower housing. I asked him to pull the starting cord slowly. I saw the slight spark jump across the gap to the metal. “There’s our spark,” I said. I put the plug back in and tightened it. The mower started after a dozen or so pulls.

“So, all it needed was a spark,” he said. “I guess that could be said for most of us.”

He said he would be glad to pay me something for my trouble but didn’t want to shut off the mower to go back inside for his wallet. He told me to stop by later, but I said I was just glad I could help. I never introduced myself. I didn’t tell him I had his Civil War series at home and had read about half of the first volume.

More than a decade later, I never missed an episode of the PBS documentary, mainly for another chance to hear Foote’s beautiful Southern drawl with its Delta grandeur. Even now, when I’m feeling at loose ends and lazy, I’ll watch a few minutes of Shelby Foote holding forth about the Civil War on YouTube.

Sometimes that little spark is all I need.

Copyright (c) 2016 by Vince Vawter. All rights reserved. Before turning to fiction, Memphis native Vince Vawter spent forty years as a newspaper journalist. He lives with his wife in Louisville, Tennessee, on a small farm in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains. His first novel, Paperboy, was named a 2014 Newbery Honor Book.