Afrofuturism and the Art of Seeing

Reflections on Tales of Wakanda and the visionary literature of the African diaspora

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This article originally appeared on May 3, 2021.

***

Younger than my sister and not yet in school, I didn’t yet have a large community of friends who would come over to play at our house. So it was always little wimpy me surrounded by her big kid friends. In playing Red Rover, I was invariably the last selected to be on a team and the first the opposite team would call over, knowing I wouldn’t break through. That’s only if they noticed me or let me play at all.

What does any self-respecting 5-year-old do in this situation but put on her superpowers? I would physically step into an invisible suit that zipped up from the tips of my toes to the top of my head.

I still can’t remember how this worked. Or maybe it didn’t actually work, but in my childhood memory I felt faster, stronger. I won sometimes. I was selected for teams. I was seen by the big kids.

Being seen is, perhaps, one of the most spectacular of powers. But so many people of African heritage had their homes and identities colonized, impacting how we are seen and how we see ourselves throughout history. It’s easy to tout platitudes of inclusion in the present, but even many imagined futures continue to place the current dominant culture in the foreground. Specifically, in futuristic arts and science fiction — mostly dominated by white males — authors often neglect to see marginalized populations as a part of the future at all.

Bestselling nonfiction author and novelist Jesse J. Holland, a native of Memphis, pointed out at a March 10 panel for Dillard University that this is one reason we need Afrofuturism. People of color “don’t show up in the future” in the hundreds of years of science fiction and fantasy arts writing. “Or if they do,” he said, “they’re stuck down in the engine room; they’re not in charge of anything … or they’re the nerdy scientist left behind in service of the white protagonist’s story.”

In a recent email exchange, author and poet Linda D. Addison put it succinctly: “It is human to see Self in the future, but being Black in America means fighting to be human, and being erased from history, the present and the future.”

Fortunately, many Black authors like Addison and Holland, along with visual artists, musicians, designers, and activists, have long learned to zip into the cloak of art we now call Afrofuturism (also kindred to Black Speculative Arts) to imagine possible futures that embrace truly liberated Black bodies and stories.

The term “Afrofuturism” was coined in the early 90s by Mark Dery in his essay “Black to the Future” as a way to put language to the possible futures and nods to science that were popping up in works by visual artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat, musicians like George Clinton and Jimi Hendrix and, of course, novels by Octavia Butler, who seamlessly wrote 40 years ago about the future in a way that feels like deep past, as well as very much our present.

But the tenets of Afrofuturism began long before it had a name. It’s about reclaiming roots, improving society for all, daring to believe in a future that might currently seem impossible. It challenges dominant culture by simply insisting upon full humanity for Black people. Slave revolts from Haiti to Southampton County, Virginia, began with the seeds of imagining another possible future. And what might you call Harriet Tubman convincing her family and friends to flee to freedom if not Tubman’s narrating another future for Black bodies?

Many early African American tales speak of the desire of slaves on the sea islands hoping to sprout wings and fly back to Africa, thus inspiring Virginia Hamilton’s popular children’s book The People Could Fly and elements of Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon. Magical flight for a possible better life? These are Afrofuturistic wings.

“Afrofuturism literature, art, music, fashion, activism, etc. is our way to re-affirm that We Are Here, and we matter as humans,” Addison noted. “We are not so much reshaping this nation as removing denial of our place in the past, present and future of this Universe and showing a more authentic picture of this country.”

Afrofuturism combines these elements of past, present, and future often by weaving in magical realism, revisioning, technology, science fiction, and world-building. Descendants of Africa become the primary architects of the world and human experience. (It’s worth noting that other groups have embraced futurism in art and culture, as well — such as Indigenous Futurism and Chicanafuturism/Nepantla — and these possible futures exist in harmony with each other.)

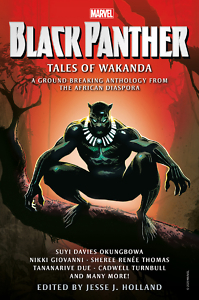

In 2018, the film Black Panther made quite the theatrical and emotional impact when Marvel introduced the first Black comic book hero to its own franchise within the Marvel cinematic universe, placing Afrofuturism back on center stage. Now Marvel’s publishing wing, which also publishes the comic books, brings us Black Panther: Tales of Wakanda, a short story collection edited by Jesse J. Holland.

Black Panther: Tales of Wakanda brings together an all-star group of poets and authors from across the African diaspora to usher us into new stories surrounding the world of Wakanda, the imagined sub-Saharan African country which was protected from colonization and is home to the fictional metal Vibranium. As a result of its protective bubble, Wakanda became the most technologically advanced country in the world. But Afrofuturism requires seeing and being seen, so this African country does not remain hidden forever.

The authors Holland selected for this collection have too many accolades to name them all, but here are a few: Addison, five-time winner of the Horror Writers’ Association’s Bram Stoker Award and newly named Grand Master of the Science Fiction & Fantasy Poetry Association; Sheree Renée Thomas of Memphis, an award-winning author and recently named editor of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction; and Knoxville-born Nikki Giovanni, renowned poet, activist, and self-described “space freak.”

Ultimately, each writer of Black Panther: Tales of Wakanda is working within a received form, considering most major characters were developed as far back as 1966 when Black Panther first appeared in U.S. comic books. The setting of Wakanda is mostly predetermined, and a basic storyline for building the world of Wakanda exists within the whole Marvel arc. But this group of writers, who usually reach into the wildest alcoves of their imagination to create work, still manage to give us 18 distinct stories that reflect the wide range of what speculative Black fiction may look like while also embodying their personal themes and style.

For example, Addison gives us characters we love like Okoye and other members of the king’s dynamic bodyguard force — the Dora Milaje — in her tale “Shadow Dreams.” If you’re a fan of these warrior women, you’ll probably smile widely while reading until the tale takes a creepy twist that Addison knows how to execute so well.

Meanwhile, in her story “Immaculate Conception,” Giovanni employs poetic license to create a “what if” tale where T’Challa is born in Oakland, California, instead of Wakanda. He, of course, meets Huey Newton and Bobby Seale of the U.S. Black Panthers, but then goes on other adventures instead of joining them. Even with Giovanni’s decidedly relaxed fairy tale tone, it was still difficult not to fear T’Challa growing up with black skin in the United States. Would his body be safe here? When they see him, how will they see him? This tension further highlights the need for Afrofuturism in art — to help Black bodies be seen alive and thriving in the midst of news cycles, which show us otherwise. And perhaps those stories keep all of us motivated as activists and in the work of casting a new vision of race relations in the nation.

While the stories are not chronological or related to one another directly, they each contribute to the mysticism of Wakandan mythology.

The collection spends a lot of time with new or lesser known characters, but also gives us special stories with the characters we’ve grown to love. King T’Challa’s sister, Princess Shuri, gets two of her own stories where she encounters vampires and Voodoo in New Orleans (“Bon Temps” by Harlan James) and completes a mission after a DNA test connects them to a woman in Baltimore (“I, Shuri” by Christopher Chambers).

The collection spends a lot of time with new or lesser known characters, but also gives us special stories with the characters we’ve grown to love. King T’Challa’s sister, Princess Shuri, gets two of her own stories where she encounters vampires and Voodoo in New Orleans (“Bon Temps” by Harlan James) and completes a mission after a DNA test connects them to a woman in Baltimore (“I, Shuri” by Christopher Chambers).

Then Cadwell Turnbull takes us right into our beloved villain Killmonger’s warring psyche with his story “Killmonger Rising.” Through Killmonger’s inner dialogue, set apart by his three names — Killmonger, Erik, and N’Jadaka — we see how he wrestles with identity and how to best seek justice for the part of the diaspora ignored by Wakanda for so many years:

As he searched, a familiar argument was happening in Killmonger’s head.

Erik: A wife, a family, a house, a career. What’s so bad about all of those?

Killmonger: Vengeance against Wakanda and the ruling family takes priority. How does luxury get us any closer to vengeance? What N’Jadaka is doing, that helps.

Erik: Jewel’s right. The best revenge is living well.

Killmonger: A life our father was denied. A life our mother was refused. Don’t forget the dead and what they sacrificed.

Of course, T’Challa remains the king of the narrative, appearing, if only by name, in every story. It’s impossible not to think of Chadwick Boseman every time you read the name T’Challa even though the Marvel stories have always breathed a separate life from the Marvel cinematic universe. But, frankly, Boseman is the once and future king of Wakanda. Forever.

A particularly tender moment that seems to gently nod to Boseman’s memory after his shocking and untimely death last year is found in Sheree Renée Thomas’ story, “Heart of a Panther.” The section begins, “As birdsong trilled in the distance, T’Challa did not fear death.” She goes on to honor him:

T’Challa learned to embrace dust at an early age. It was the dust that taught him how to live through grief, and it was dust that his body would return to, to nourish the earth while his spirit joined the realm of the ancestors.

Chadwick, we see you.

In the first story of the collection (“Kindred Spirits” by Maurice Broaddus), King T’Challa greets his adopted brother saying, “Sawubona.” Broaddus then explains that this greeting means, “I see you and by seeing you I bring you into being.” Meaning, the act of seeing someone impacts their future and their becoming.

The act of being seen pulses through the entire collection. And I also see that little me with her superpowers. She would have surely been decked out in Dora Milaje garb at the movie theater with my parents if the Black Panther film franchise existed then. And she would have insisted on a trip to the bookstore for more Wakandan delight, reading way past bedtime by the mild orange glow of the nightlight, eager to encounter this fantasy world in which she was fully seen.

Holland — who is also the author of the 2018 novel Who Is the Black Panther? — surely sees her, too, which is why he’s so committed to ushering Black Panther into the prose world. As he writes in the introduction to Tales of Wakanda, “T’Challa’s world needs, nay deserves, the same kind of exploration in prose form as Bruce Wayne’s did, told by writers who appreciate and admire the world of Wakanda in the same way writers adored the world of Gotham a couple of decades ago.”

Wakanda, sawubona.

Ciona Rouse is the author of the chapbook Vantablack (Third Man Books, 2017). Her poetry has appeared in Oxford American, NPR Music, The Account, Talking River, Gabby Journal, and other publications. She is poetry editor of Wordpeace. Along with poet Kendra DeColo, Rouse hosts the literary podcast Re\VERB.