An American Story

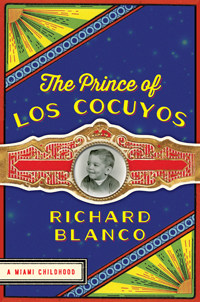

Inaugural poet Richard Blanco talks with Chapter 16 about his new memoir

Richard Blanco brings a poet’s keen eye for observation and a prose writer’s gift for plot to his new memoir, The Prince of los Cocuyos, which illustrates how cultural, sexual, and artistic sensibilities are “all developed—not independently of each other—but simultaneously,” as he tells Chapter 16. Throughout the book, Blanco and his family, who emigrated from Cuba, seek community, understanding, and acceptance in their new land, but they also cling to reminders of home: Blanco’s grandfather chops down pines and hollies and replaces them with Cuban papaya and avocado. Blanco himself—who, besides growing up in a bi-cultural world, is also gay—successfully navigates both the aisles at Winn Dixie and Cuban bodegas, wondering all the while where he belongs. He recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: Throughout The Prince of los Cocuyos, many details speak to your need—and your family’s need—to feel connected to your heritage and landscape, yet too often people unfairly expect immigrants to act “American” once they arrive in the U.S. Did your experience as Barack Obama’s inaugural poet in any way inform your own understanding of what it means to be “American”?

Chapter 16: Throughout The Prince of los Cocuyos, many details speak to your need—and your family’s need—to feel connected to your heritage and landscape, yet too often people unfairly expect immigrants to act “American” once they arrive in the U.S. Did your experience as Barack Obama’s inaugural poet in any way inform your own understanding of what it means to be “American”?

Richard Blanco: Yes, indeed—very much so. Growing up in an immigrant family I somewhat still felt that I wasn’t entirely “American.” I thought being “American” meant being like one of those little boys on TV shows like Leave it to Beaver, and that the “American” story was some other narrative, not mine. But as I was waiting to be called up to the podium at the inauguration, it hit me all of a sudden: my story, my parents’ stories, and the stories of each of those 850 thousand people gathered on the National Mall—were the American story—always had been.

There I was: a gay Latino immigrant about to address the entire country. I turned to my mother, who was sitting next to me, and said: “Mamá, I think we’re finally Americanos.” The greatest gift of being honored as presidential inaugural poet was to finally be given a place at the American table, so to speak—to realize that I was finally home—had been home all along.

Chapter 16: It’s evident that poetry’s emphasis on specific, vivid detail and belief in letting the image do the work helped your transition into memoir. What did you find to be the most challenging about writing in this genre?

Blanco: One of the defining differences between prose and poetry is that the latter is not plot-driven. Poems work their magic through imagery, sound, figurative language, etc.—even narrative poems. Though much of my poetry is narrative, my greatest challenge was to remember to keep telling a story, so to speak. I had to keep asking myself, “Okay, what happens next?” and write toward that end. As a poet there was an tendency to linger a bit too long on an image or a metaphorical moment, and forget to keep the narrative moving; I had to train myself to use poetic devices more sparingly and only at exactly the right times.

Chapter 16: In “52 Statements about Poetry,” Marvin Bell wrote that “prose is prose because of what it includes: poetry is poetry because of what it leaves out.” Your memoir, however, pushes on either side of his definition. The essays that make up this collection are not weighed down by a comprehensive description of your childhood; instead the book highlights seemingly quiet events that helped you come to understand who you are. How did you decide what to include and what to leave out?

Blanco: From the start I was interested in examining the complex ways in which my cultural identity, my sexuality, and my artistic sensibilities all developed—not independently of each other—but simultaneously—how they collided and intersected, mingled and braided to form me: a Cuban-American, gay, poet engineer. Every being is a result of a unique set of circumstances, influences, and forces; each of us is a unique “recipe,” and I wanted readers to recognize this in my story as much as in their own lives. And so, as I ran through my mental catalog of memories, anecdotes, and family lore, I zeroed on those that spoke to that complexity—that’s how I decided what to include and, what’s more, how to shape and arrange these into a narrative that would highlight these themes.

Chapter 16: Continuing in that vein, is there a story that you really wanted to tell but couldn’t find a way to include in The Prince of los Cocuyos?

Chapter 16: Continuing in that vein, is there a story that you really wanted to tell but couldn’t find a way to include in The Prince of los Cocuyos?

Blanco: Great question! I looked back over my notes and think I managed to “tell” every story I felt was important to the book, which is to say, every story I “wanted” to tell. However, there were a few snippets of memories that never found a narrative, and those I had to leave out, namely my infatuation with Bonny, who was one of only a handful of Americanos in my kindergarten class; the first time I played in the snow in Miami—man-made snow at a church carnival; the piñata my mother lovingly hand-made for my ninth birthday party; and my crush on the Six Million Dollar Man (Steve Austin). Perhaps these will be poems someday. The process of writing memoir inadvertently taught me how to better distinguish which inspirations/memories are better suited for poems, and which would make better stories.

Chapter 16: These essays (or would you call them chapters?) end in ways that good poems tend to end: with an image or bit of dialogue instead of overt editorializing. Was that a conscious decision?

Blanco: I would call these chapters—or “pieces,” really. I wanted each piece to work independently from the rest of the book and satisfy the reader on its own—like a short story almost. And yet, I also wanted the pieces to work together to form a narrative arc for the book as a whole. I was interested in blurring the genre lines between short story, memoir, and poetry.

As for not editorializing, yes it was a very conscious decision indeed. In fact, I had to constantly “fight” the urge to neatly sum up or comment on the “meaning” of key moments or the end of each piece. Similarly to how I once learned to trust the imagery in poems, I had to learn to trust the narrative in the memoir. In other words, to just let the story speak for itself. It was a relearning of the old adage: show; don’t tell.

Chapter 16: Your abuela, who lived with you, is a central figure in this collection. She appears in the book’s first sentence, and her death is foreshadowed in its penultimate page. Love, frustration, admiration, fear—even hate—are all bundled together in your portrayal of her. While writing this book, did you come to any new realizations about your relationship?

Blanco: Before this memoir, I mostly harbored anger and hate for my abuela. Through the process of writing, I was able to unearth many more emotional layers, and also discover a deeper understanding of my grandmother, who was far more complex than I had thought. As I wrote in the acknowledgements: “[T]hese pages have let me hate her, understand her, forgive her, and thank her for her failed attempts at making me un hombre, which indirectly made me a writer. Te quiero, abuela.” I think that says it all—and more: one of the reasons I am addicted to writing is because it makes us investigate, process, feel, and ultimately discover some new truth.

Chapter 16: One thing this book reveals is what a wonderful, surprising life you have led. What would you like to accomplish next?

Blanco: Since becoming presidential inaugural poet, I’ve engaged tens of thousands of people as a public voice and figure on stage from the podium. This has piqued my creative curiosities, and I’ve started to think about the intersection between drama, poetry, and memoir. I’m becoming interested in exploring how to write for the stage and/or the camera, and wondering what it might be like to act in something I may write someday. But for now this lies in what I call my “wonder” pile. My more immediate plans are to publish a fourth collection of poetry and a follow-up memoir about my visits to Cuba.

[This article appeared originally on August 27, 2014. It has been updated to reflect new event information.]

Charlotte Pence, a Ph.D. graduate of the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, is the author of a forthcoming poetry collection, Many Small Fires, which will be published by Black Lawrence Press in January 2015. She is an assistant professor of English at Eastern Illinois University.