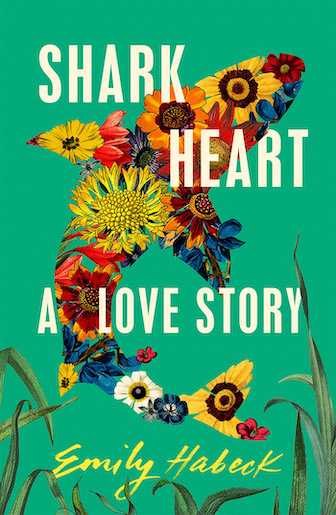

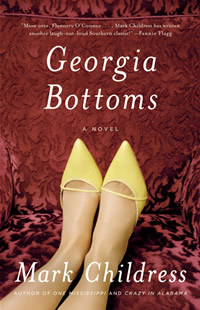

An Honest Woman

In Georgia Bottoms, Mark Childress delivers a comic sendup of small-town pretensions

“Don’t blame me,” muses Georgia Bottoms, the title character of Mark Childress’s seventh novel. “The world was this way when I got here.” Georgia needs no better rationale for her madcap existence in Six Points, Alabama, population 3,394, “a town so far from the interstate, so far behind the times that it had no cable TV, no Walmart, McDonald’s or Starbucks, and hardly any A/C.” Given the absence of such modern distractions, it’s all the more remarkable that Georgia manages, as she closes in on forty, to remain the town bombshell while also supporting her aging mother and ne’er-do-well brother, keeping up their sagging antebellum mansion, and making regular contributions to a mysterious New Orleans charity case via Western Union—and without missing a single Sunday service at the First Baptist Church. More astonishingly, Georgia is largely able to do so through the support of a revolving-door cast of gentleman—including the pastor, the sheriff, a prominent judge, and a bank president—all of whom are devoted to her charms and completely unaware that they are not the only “caller” entertained by Miss Georgia in her garage-apartment boudoir.

We meet Georgia Bottoms in the sweltering summer of 2001, as she settles into her family pew at the First Baptist, preparing to spend the hour trying to ignore the heat and pretending not to be bored. Before long, however, Georgia realizes that the preacher, Eugene Hendrix—who, only hours before, lay supine in a pair of black-silk boxer shorts on Georgia’s four poster bed—is about to make a monumental confession that will expose the double life she’s worked so tirelessly to establish and maintain. If any aspect of Georgia Bottoms stretches credulity, it’s the notion that a flirtatious, voluptuous single woman in a town as small as Six Points could juggle six boyfriends—all of them pillars of the community, and all but one of them married—without drawing a hint of suspicion. But as she calls on her shrewd wit and relentlessness to avert disaster, Georgia proves herself the exception to many rules.

Mark Childress’s previous novels, especially Crazy in Alabama and One Mississippi, have earned a wide audience for their casts of Southern eccentrics, their brilliantly executed scenes of comic farce, and for the casual wit of Childress’s voice, which is frequently scathing but never cruel. A former editor for Southern Living magazine, Childress is brilliant in his rendering of the details of a small-town Alabama socialite’s life, from her taste in dresses—“she needed a pink, well-rested complexion to set off the gorgeous emerald-green Lauren by Ralph Lauren dress she had special-ordered from the big Belk’s in Mobile”—to the menu and décor of her annual September ladies’ luncheon: “Georgia didn’t own the fifty shot glasses needed to give each guest her own serving of the Lobster Scallion Shooters. In a burst of inspiration, she’d had Fred at Hull’s Market order two cases of votive-candle holders, which she now had to wash, dry, and scrape the price tags off until her thumbnail was a ragged rim of gray sticky cheese.”

Mark Childress’s previous novels, especially Crazy in Alabama and One Mississippi, have earned a wide audience for their casts of Southern eccentrics, their brilliantly executed scenes of comic farce, and for the casual wit of Childress’s voice, which is frequently scathing but never cruel. A former editor for Southern Living magazine, Childress is brilliant in his rendering of the details of a small-town Alabama socialite’s life, from her taste in dresses—“she needed a pink, well-rested complexion to set off the gorgeous emerald-green Lauren by Ralph Lauren dress she had special-ordered from the big Belk’s in Mobile”—to the menu and décor of her annual September ladies’ luncheon: “Georgia didn’t own the fifty shot glasses needed to give each guest her own serving of the Lobster Scallion Shooters. In a burst of inspiration, she’d had Fred at Hull’s Market order two cases of votive-candle holders, which she now had to wash, dry, and scrape the price tags off until her thumbnail was a ragged rim of gray sticky cheese.”

But within the frequently hilarious asides and slapstick capers that propel the narrative of Georgia Bottoms, Mark Childress weaves the characteristic insights and perspectives that have earned him critical as well as popular acclaim. Few novelists could critique the lingering problems of race in the Deep South as daringly as Childress, or draw in national disasters like the 9/11 attacks and Hurricane Katrina both as comic effects and potent commentaries on the bittersweet insularity of small-town life. Childress also deftly draws in Southern embarrassments like Alabama Chief Justice Roy Moore’s Ten Commandments monument and racial gerrymandering in local politics.

Moreover, in Georgia Bottoms, a woman a bit too larger-than-life for her time and place, Childress presents a provocative image of a single woman navigating the hypocrisies and repressive traditions that still work their subtle damage in the lives of women in much larger and ostensibly more progressive locales than Six Points, Alabama. “A woman without a husband isn’t supposed to be happy, but Georgia was,” Childress writes. “A woman alone is not supposed to have fun . . . but Georgia had it all, and then some. Women are supposed to hate the idea of getting older, but Georgia knew she would be fine if it ever did happen to her. She would give up makeup and dieting, sit all day in front of the TV, happily eating peanut M&M’s. Hell, bring it on!”

Moreover, in Georgia Bottoms, a woman a bit too larger-than-life for her time and place, Childress presents a provocative image of a single woman navigating the hypocrisies and repressive traditions that still work their subtle damage in the lives of women in much larger and ostensibly more progressive locales than Six Points, Alabama. “A woman without a husband isn’t supposed to be happy, but Georgia was,” Childress writes. “A woman alone is not supposed to have fun . . . but Georgia had it all, and then some. Women are supposed to hate the idea of getting older, but Georgia knew she would be fine if it ever did happen to her. She would give up makeup and dieting, sit all day in front of the TV, happily eating peanut M&M’s. Hell, bring it on!”

Georgia is no saint—far from it. Her career as a professional mistress is a fine hair from prostitution: “She never asked anyone for money. Whatever happened to be left atop the highboy was a gift, freely given.” To account for the time she spends catering to the fantasies of her “lovers,” Georgia pretends to be crafting handmade quilts, which, in actuality, are purchased from a group of African-American quilters in a distant town and then sold at a huge mark-up. But, as Georgia’s antics become increasingly titillating and scandalous, Childress peels away the layers of the image she’s built around herself to reveal her genuine decency. Georgia is surviving by the only means available to her, and, in the end, proves herself, against all odds, to be an honest woman.

Mark Childress hails from Monroeville, Alabama, lifelong home of Harper Lee and childhood refuge of Truman Capote, from whom Childress has doubtlessly inherited his characteristic flair for dry, comic satire. It’s easy to imagine Georgia Bottoms as what Holly Golightly might have become if she’d never fled Texas. Childress parts from Capote, however, in his effortless generosity toward his flawed but unfailingly endearing characters. Childress’s obvious affection for the peculiar lot of Six Points makes them easy to laugh at and impossible to judge. In Georgia Bottoms, he has created a protagonist too imperfect to qualify as a true heroine, but too clever and, in her own unique sense, too moral not to be admired.

Mark Childress will appear at the 2011 Southern Festival of Books, held October 14-16 in Nashville.