An Irrepressible Phenomenon

Remembering Memphis novelist Mark Behr, who died on November 27

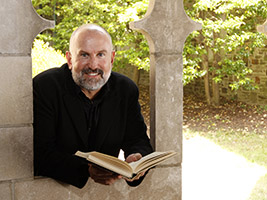

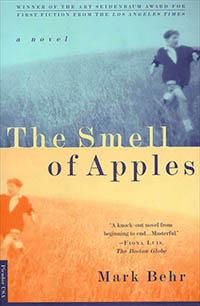

Mark Behr arrived at Rhodes College six years ago from the College of Santa Fe. I first heard about his candidacy from a colleague, who came running down the hallway one afternoon with the news that the Tanzanian-born author of The Smell Of Apples, which he had been teaching for the last five years, had just applied for our job opening in the English Department. Not quite believing our luck, two of us interviewed him by phone. And that was the first time we heard his unforgettable voice and his gorgeous, arresting accent. Afterwards, we looked at each other and said, almost simultaneously, “I am in love with this man.” The teaching demonstration he gave during his campus visit will never be bettered. In their evaluations of this sample class, the students all wrote in giant capital letters, “PLEASE, PLEASE HIRE THIS GUY!” and “THAT WAS THE SINGLE BEST CLASS I HAVE EVER TAKEN IN MY LIFE.”

That one-off teaching demonstration was no fluke. Mark’s classes were a thing apart. His students entered his classroom with one identity and finished the semester with another. Although it is overused, the only word that properly describes his teaching is “transformative.” Another word, one that Mark himself loved, is “formidable.” He was formidable and transformative. On five continents. If you were lucky enough to be one of his students, he routinely promised to destroy you, to fail you, to go for the jugular. To change your life.

That one-off teaching demonstration was no fluke. Mark’s classes were a thing apart. His students entered his classroom with one identity and finished the semester with another. Although it is overused, the only word that properly describes his teaching is “transformative.” Another word, one that Mark himself loved, is “formidable.” He was formidable and transformative. On five continents. If you were lucky enough to be one of his students, he routinely promised to destroy you, to fail you, to go for the jugular. To change your life.

Everyone in the English Department knows these Behr-isms. But there was a central part of Mark that could only be experienced in his first continent—that is, Mark the South African. When my family traveled with him in Cape Town and Kruger National Park for two weeks in 2014, we got to see Mark in his natural habitat. Heidegger writes at great length about our sense of not being at home in our world, of feeling alienated and inauthentic. The Mark my family saw in South Africa was a different Mark than the one we encountered here in Memphis. In a way that is hard to describe, Mark in South Africa was more completely at home in the world than many of us will ever feel.

Mark Behr often called our attention to “normative heterosexual biases” and tirelessly demanded that we see through the power structures that control us, that we locate the sexism and racism upon which so much of these structures are built. And he always included himself among the complicit. But this critique was only half the story. Mark stripped away those human-made constructs so that we could see the remarkable animal in each of us. It is no mistake that one of the most affectionate things he could call you was “Animal.” It’s also no mistake that he delighted in trying to figure out what animal we each reminded him of. Animals weren’t interesting to him because they reminded him of humans. Humans were interesting because they reminded him of animals.

During our time in Kruger, we spent eight hours a day driving slowly across dirt and asphalt roads with our gaze focused intensely at the vast landscape around us. We were there to do one thing: spot animals. And as we spotted, we giggled; we told stories. Mark taught my children dirty limericks and nursery rhymes in Afrikaans. No music on the radio, no cell-phone service, no work talk: nothing but the six of us in that van, surrounded by the blameless majesty of the African bush, where Mark was born and grew up. In the course of those two weeks, Mark effortlessly identified at least fifty different species of birds.

During our time in Kruger, we spent eight hours a day driving slowly across dirt and asphalt roads with our gaze focused intensely at the vast landscape around us. We were there to do one thing: spot animals. And as we spotted, we giggled; we told stories. Mark taught my children dirty limericks and nursery rhymes in Afrikaans. No music on the radio, no cell-phone service, no work talk: nothing but the six of us in that van, surrounded by the blameless majesty of the African bush, where Mark was born and grew up. In the course of those two weeks, Mark effortlessly identified at least fifty different species of birds.

We watched in wonder as towers of giraffe passed in front of our van with ponderous prehistoric grace. We saw prides of lions, families of elephants, huge stampeding herds of Cape buffalo, and the slow heavy stroll of rhinos. Mark took unflagging delight in each new spotting. One particular refrain—and this was quintessential Mark—occurred whenever we’d see in the distance a traffic jam. Stopped cars meant a significant discovery: a lounging lion or an impaled impala lay ahead. With increasing excitement Mark would press the gas and hunch over the steering wheel, exclaiming to our boys, “Look here, look here!” And then, in unison, the entire car would erupt, “A situ-A-tion!”

The episode that stays with me, however, was our morning with the baboons. We stumbled upon a group of twenty or so, dawdling across a scattering of low branches against the pale sunrise. The children wrestled and swung from branches. The adults looked on impassively. Couples carefully picked fleas from each other. To Mark’s wicked amusement, one annoyed parent yanked a particularly naughty and annoying baby from a scrum and spanked it angrily, yielding a squeal. We watched the group in rapt fascination for a good half hour.

As we began to retreat, Mark recalled an essay by J.M. Coetzee that traces the prevalence of the concept of “idleness” in the Dutch settlers’ seventeenth-century observations of the Hottentots, who lived on the Cape of Good Hope. Before the Dutch arrived, Mark explained, the Hottentots existed in a sort of prelapsarian paradise, a life in which man is not condemned to earn his bread by the sweat of his brow but instead spends his days dozing in the sun. The Dutch settlers, of course, dismissed the Hottentot’s paradisal life as slothful and idle. And there followed the unimaginable horror of Western colonialism. Mark fell quiet, and in that moment I had a glimpse of what it meant to be at home in Mark’s world, which truly is ground zero for all of us, because, as evolution reveals, we are all Africans.

Mark was our colleague, our friend, our teacher, our mentor, our mischief maker, our provocateur. He was like no one else I have ever met or will ever meet again. So in the spirit of the irrepressible phenomenon that was Mark Behr, I urge you to be playful and empathetic, vital and open-minded. Go forth and find your inner animal.

[To read more about Mark Behr, click here and here.]

Copyright (c) 2015 by Marshall Boswell. All rights reserved. Marshall Boswell is the author of two works of fiction—Trouble with Girls and Alternative Atlanta—as well as scholarly works on John Updike and David Foster Wallace. Boswell serves as chair of the English Department at Rhodes College. This essay was adapted from a eulogy written—with the help of Boswell’s colleague and wife, Rebecca Finlayson—for a memorial service held on December 4, 2015.