An Ode to Strength

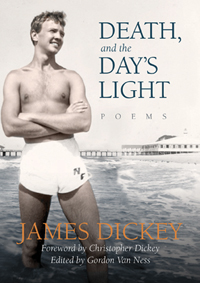

At the end of his life, as his own power waned, James Dickey was still writing about joy

“My true self was everywhere lying and living,” James Dickey writes in “For Jules Bacon,” the second of two epic poems that comprise the majority of his posthumously published new collection. “All I had to do was pick.” Death, and the Day’s Light embraces both senses of that last word: the sense of choosing, as well as picking up the pieces.

Dickey began composing some of these poems as early as the 1970s—at the height of Dickey’s celebrity as a Guggenheim Fellow, a winner of the National Book Award, and of course the author of Deliverance—and this collection echoes the eternal, obsessive themes of Dickey’s work: war and love, life and death, the clarifying power of a shared struggle. But these poems also reflect the concerns of a man at the end of his life. Set firmly in the physical world, they speak to the link between body and spirit: as the body breaks, the spirit builds.

“Show Us the Sea” and “For Jules Bacon,” a poem honoring Mr. America 1943, belong to a section of Death, and the Day’s Light titled “Two Poems on the Survival of the Male Body,” and both are at least nominally about weight lifting. But beyond that obvious concern with physique, the true subject of the poems is choice: choosing meaning, defining struggle. In “For Jules Bacon,” a hunk of steel becomes an emblem of Dickey’s own military service, the weight which leads to personal growth. The implication throughout is that the volitional self was once everywhere, even if the power to choose has largely disappeared with age for the “I-figure,” as Dickey terms a poem’s speaker.

“Show Us the Sea” and “For Jules Bacon,” a poem honoring Mr. America 1943, belong to a section of Death, and the Day’s Light titled “Two Poems on the Survival of the Male Body,” and both are at least nominally about weight lifting. But beyond that obvious concern with physique, the true subject of the poems is choice: choosing meaning, defining struggle. In “For Jules Bacon,” a hunk of steel becomes an emblem of Dickey’s own military service, the weight which leads to personal growth. The implication throughout is that the volitional self was once everywhere, even if the power to choose has largely disappeared with age for the “I-figure,” as Dickey terms a poem’s speaker.

Still, even at its end, life itself lives on in these poems, passed down in “Show Us the Sea” by the speaker to his son—the strong, flexing figure on the beach. “It takes no muscle, son, to rejoice,” the speaker says:

As it happens,

I am rejoicing without muscle, without any youth

But yours.

Dickey, who earned a degree at Vanderbilt following his service during World War II, had a storied youth of his own, which his son Christopher Dickey can’t help but mention in a foreword to Death, and the Day’s Light: the powerful early collections—Drowning With Others (1962), Helmets (1964), and Buckdancer’s Choice—that in time gave way to the drinking. The truly incredible drinking. It’s no wonder it took so long for these poems to find their way to readers. Ultimately Gordon Van Ness, a scholar and personal friend of the poet, combed through eight annotated drafts, in some cases, and nearly forty years of notes and revisions to put this collection together and see it into print nearly two decades after Dickey’s death.

The poems in Death, and the Day’s Light can be repetitive, though in a manner that mostly serves the content here, expressing the cycle of life and death, and the rhythms of the ocean as it continually stretches out and pulls back, folding in on itself. With a posthumous collection like this, it might be tempting to wonder how much of the repetition was simply Dickey riffing in search of the best phrase and might have been cut by the poet himself if he had lived long enough. But incantatory language is such a hallmark of Dickey’s work at every stage of his career that any reader familiar with his poems will see this collection as a natural extension of his life’s work.

In the surf-tossed lines of “Show us the Sea” and other poems in Death, and the Day’s Light, in fact, Dickey is as powerful and direct and contentious as ever. For him, even the sea is at odds with itself, “The backrush dragging like shovels,” digging its own grave. We see the poet as witness, using his last, final voice to summon all of life in “A strange other tongue, a new language to go with the cries to go / With the sound of the conch-shell.”

Luke Wiget earned an M.F.A. in fiction from The New School, and his writing has appeared or is forthcoming in SmokeLong Quarterly, The Rumpus, and Heavy Feather Review, among others. A recent transplant to Tennessee by way of Brooklyn, he lives in Nashville.