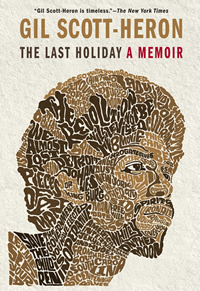

Artist, Activist, Icon

In his memoir, The Last Holiday, musician/poet Gil Scott-Heron traces his path from budding artist to pop culture prophet

“Politics was not my favorite topic on poetry stops—or in life.” Those are surprising words coming from musician/poet Gil Scott-Heron, who is best known, and widely revered, for brilliant, politically radical spoken-word pieces like “Whitey on the Moon” and “The Revolution Will Not be Televised.” But as Scott-Heron, who died in 2011, explains in his posthumously published memoir, The Last Holiday, anyone “alive on the planet earth and Black” in the late twentieth century “got the short end of every stick except the nightstick, and there was damn near no way you could not have political pressure on you and therefore have political opinions.” Thus, Scott-Heron—a natural poet who had a keen writer’s eye even in boyhood—became both an activist and an artist as he used his gifts to report what he saw in a life that took him from segregated Jackson, Tennessee, in the 1950s to a permanent place in the pop culture pantheon.

Scott-Heron’s recollections of his early years in Jackson, where he was taken as a toddler to live with his grandmother in the wake of his parents’ split, depict a remarkably cohesive and close-knit community. The South Jackson neighborhood where he lived, he says, “felt like a town full of parents and grandparents,” and Lily Scott, a highly respected figure who had a reputation for being defiant in the face of segregation and white privilege, doted on her grandson. “Words have been important to me for as long as I can remember,” Scott-Heron writes, and his grandmother nurtured that love of words, teaching him to read at the age of four, using comics, the Bible, and The Chicago Defender, a venerable African-American weekly. Scott-Heron recalls this period of his life in vivid, often lyrical terms that suggest his artist’s sensibility developed early. Describing the dilapidated Catholic school he attended, he writes of “nun-women in dust-dragging black” and “shadow-cloaked hallways filled with an eternity of God-fearing intimidation.”

Lily Scott died when Scott-Heron was eleven, and he went to live in New York City with his mother. The move ultimately set the course of his life, introducing him to a larger world than small-town Jackson and putting him in the way of an education that fostered his talents. He landed a scholarship to The Fieldston School, a prestigious prep school that counts renowned photographer Diane Arbus and her brother, U.S. Poet Laureate Howard Nemerov, among its alumni. Scott-Heron regarded Fieldston as a sort of alien but benign territory where he was neither shunned nor embraced, but his recollections of the place are characteristically wry and lively. He engaged in a protracted war of wills with a teacher over his playing of an off-limits piano, and his account of the meeting between his mother and the school’s disciplinary committee is a crosscultural showdown that reveals just where Scott-Heron got his verbal firepower and his remarkable personal presence.

Lily Scott died when Scott-Heron was eleven, and he went to live in New York City with his mother. The move ultimately set the course of his life, introducing him to a larger world than small-town Jackson and putting him in the way of an education that fostered his talents. He landed a scholarship to The Fieldston School, a prestigious prep school that counts renowned photographer Diane Arbus and her brother, U.S. Poet Laureate Howard Nemerov, among its alumni. Scott-Heron regarded Fieldston as a sort of alien but benign territory where he was neither shunned nor embraced, but his recollections of the place are characteristically wry and lively. He engaged in a protracted war of wills with a teacher over his playing of an off-limits piano, and his account of the meeting between his mother and the school’s disciplinary committee is a crosscultural showdown that reveals just where Scott-Heron got his verbal firepower and his remarkable personal presence.

During his college years at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, Scott-Heron came into his own both as a writer and a musician. Through a remarkable combination of confidence and good luck he managed to get his first novel, The Vulture, published, and he began writing songs and playing with different groups around New York City. In 1970, after leaving Lincoln, he recorded the spoken-word album, Small Talk at 125th and Lenox, which contained both “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” and “Whitey on the Moon.” Scott-Heron would go on to earn a master’s degree in creative writing from Johns Hopkins University and publish another novel, The Nigger Factory, but his work as a writer never gathered the momentum of his musical career, which focused on a combination of soul-inflected jazz and spoken-word performance. He ultimately recorded more than a dozen albums and received a posthumous Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2012.

The second half of The Last Holiday is largely devoted to Stevie Wonder’s Hotter Than July tour (1980-81), in which Scott-Heron was a featured performer. Wonder used the tour to promote legislation that established the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday. According to his publishers, giving Stevie Wonder proper credit for his role in making the holiday a reality was Scott-Heron’s primary motivation in writing a memoir, but unfortunately he died before he was able to realize his purpose fully. In contrast to the first part of the book, the writing about the tour is less polished, often repetitive or disjointed. The story gets told, if somewhat confusingly, and while Scott-Heron’s stylistic flair is not absent, the whole section has an aura of editorial rescue about it. The finest passages in the later part of the book come when Scott-Heron returns to his own life, and particularly when he writes about the death of his mother. Walking around her empty apartment, he recalls her criticisms, which “left no visible bruise but smuggled a bone-deep ache,” and then has a poignant realization: “There was no one I could be close to now.”

The second half of The Last Holiday is largely devoted to Stevie Wonder’s Hotter Than July tour (1980-81), in which Scott-Heron was a featured performer. Wonder used the tour to promote legislation that established the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday. According to his publishers, giving Stevie Wonder proper credit for his role in making the holiday a reality was Scott-Heron’s primary motivation in writing a memoir, but unfortunately he died before he was able to realize his purpose fully. In contrast to the first part of the book, the writing about the tour is less polished, often repetitive or disjointed. The story gets told, if somewhat confusingly, and while Scott-Heron’s stylistic flair is not absent, the whole section has an aura of editorial rescue about it. The finest passages in the later part of the book come when Scott-Heron returns to his own life, and particularly when he writes about the death of his mother. Walking around her empty apartment, he recalls her criticisms, which “left no visible bruise but smuggled a bone-deep ache,” and then has a poignant realization: “There was no one I could be close to now.”

The Last Holiday has so many flashes of brilliance and provides such a vivid, intimate glimpse into the mind of Gil Scott-Heron that it is sad to think of the book it might have been if he had survived to complete it. As it stands, it reads like a flawed first run-through of one of his great performance pieces: not quite what he, or we, might want it to be, but nevertheless moving and worthy, with an unmistakable touch of genius.