As Much Belowground as Above

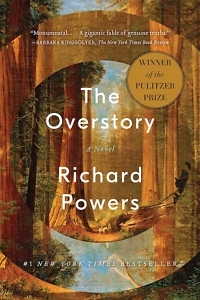

A writer returns to the Smoky Mountains and The Overstory

I have come here to the mountains as I always do — running away from my life and toward my own nature. Or away from an illusion of my life and toward some truer knowledge of it. Or away from my life’s deafening feedback and toward a deeper listening station. But what am I really running toward, or listening for, when I come here?

I know I’ve come here, to the Smoky Mountains, to reread Richard Powers’ novel The Overstory. Since my husband and I arrived earlier in the day — winding up familiar switchbacks and the narrow cliffhanging road that leads to a tiny rental cabin where I’ve come on writer’s pilgrimage countless times during the past decade — a line from the novel, spoken by the unfathomably complex world of trees, has repeated in my thoughts on a loop:

I know I’ve come here, to the Smoky Mountains, to reread Richard Powers’ novel The Overstory. Since my husband and I arrived earlier in the day — winding up familiar switchbacks and the narrow cliffhanging road that leads to a tiny rental cabin where I’ve come on writer’s pilgrimage countless times during the past decade — a line from the novel, spoken by the unfathomably complex world of trees, has repeated in my thoughts on a loop:

“If your mind were only a slightly greener thing, we’d drown you in meaning.”

I don’t pretend to know what the immense effort of writing The Overstory took out of Powers, but I do know that by the end of that period he had uprooted his life on the West Coast and relocated to the Smokies, compelled by the restorative presence of these old-growth forests. He told The New York Times he’d become so drained by the experience that he’d doubted he would write another novel.

But then came 2021’s Bewilderment, a book that turns on potent, thrilling scenes set in the Smokies. It’s tempting to read the novel as an expelling of dammed-up grief for the climate decimation Powers so masterfully engaged in The Overstory. It’s tempting to regard it as evidence of a writer who cannot yet leave a particular kind of forest.

A novel is an ecosystem. Some are deserts, built to thrive on arid conditions. Others teem with swift-moving river life, fecund and fast. The Overstory is like the Smokies — a lush host to manifold inhabitants, some knowable to the casual visitor and others elusive, inscrutable. Its world is unhurried but sure in the strength of its purpose. This enveloping ecosystem of interrelated characters, human and nonhuman, seems to have no beginning or end. In its abundance, its intensity, its strangeness — these gifts of immersion are The Overstory’s truest offerings.

The first section of the novel, “ROOTS,” introduces the nine main characters in a suite of short stories, each one haunting and engrossing, each setting its character’s fate in relation to trees. A brief lyrical prologue begins on a simple but crucial image:

“A woman sits on the ground, leaning against a pine. Its bark presses hard against her back, as hard as life. Its needles scent the air and a force hums in the heart of the wood. Her ears tune down to the lowest frequencies. The tree is saying things, in words before words.”

This novel invites us to attune ourselves as best we can, to voices we are unaccustomed to hearing — the nonhuman voices populating our world. The “chorus of living wood” shows this woman the limitations of her human perception. They tell her, “All the ways you imagine us … are always amputations. Your kind never sees us whole. You miss the half of it, and more. There’s always as much belowground as above.”

I stand barefoot on my cabin’s porch, surrounded by the canopy world of familiar trees. Our first night here, I stand alone in the rich quiet dark and begin a familiar process — of letting my citified self, my domestic self, fall away. All it takes is this mountain air, fed me by these old friends, these familiar trees. The Smokies never fail me — they give me back to myself in moments.

But below me, from the dark, I hear a pattern of clear, loud steps in the understory. I know these steps are not human. I know they are not made by small paws. I know they are happening just below me and that I am not alone. The air grows pressurized as I know I am observed.

This is what I say I want, I tell myself. Not just the absence of the human world, but the presence of the nonhuman. The step pattern repeats below me, followed by a stretch of thicker quiet. I hear no more steps but am not ready to be seen. I move away from the porch railing and back into my well-lit human world.

***

In another lyrical passage much later in the novel, Powers places one of his nine human protagonists on his back, lying on the forest floor and looking up into the high canopy world of the white spruces that tower over him. These trees communicate “in media of their own invention,” changing this man as he opens himself toward them. “They speak through their needles, trunks, and roots. They record in their own bodies the history of every crisis they’ve lived through.”

When he can hear them, they give a warning: “Long answers need long time. And long time is exactly what’s vanishing.” Soon trees from farther afield join in, offering their own message: “The world is turning into a new thing.”

Near the southern edge of the Great Smoky Mountain National Park, along the bank of the Oconaluftee River sits a particular stone, exactly the height and levelness to serve as a writing perch. I have come here again and again: to read, to scribble, to realign myself with a deeper sense of purpose, to consider the future. I came here alone for years, then gingerly described this spot’s importance to Greg, my then-boyfriend. Gingerly, I brought him here. He asked me to marry him.

Directly across the Oconaluftee from my stone sits a tree I’ve come to believe I know well. A decade ago, I named her the Daphne Tree. Yes, her. Skirts of exposed twining roots keep her gripped against the river’s edge, but they appear to have caught her in mid-turn, as does the arc and shape of her trunk, like hips. Was she fleeing her Apollo? That was my projection, of course. The last thing I wanted back then was to be caught. I ran to the mountains any chance I could, basking in my solitary life. Greg had no idea that at the moment he proposed to me, the only witness was my Daphne.

By then, just as The Overstory’s chorus of trees proclaims, I was turning into a new thing. I had invited him to my riverbank. I welcomed her witness. I could only hope she welcomed mine.

***

Hours deep into quiet work, I reach what I know is the heart of time here. With Greg off for a day of hikes in the park, I am back on the porch, reading and writing at a corner table amid glowing green canopy. I seem to cross the threshold I have longed to cross, softening back into my animal nature. I breathe deeper. I imagine I, too, am greening.

And I hear the familiar step pattern below me. The sound is so loud and clear that I know, as soon as I look down, I will see this creature emerge from the understory.

The bear, now directly beneath me, is far larger and older than any bear I’ve encountered in the Smokies — and in any case, those sightings all occurred at blurry distance. Those were roly-poly babies, who seemed all too pleased to frolic and pose for whatever tourist crowd had gathered to admire them.

This bear is enormous, black but glowing brown with caked dirt clinging to its fur, arch-backed and heavy-pawed, taking its time on the mossy ground just a few feet below me. I’m not afraid, but I can feel my cells electrified, filled with an exhilaration that is total, elemental.

Slowly, I gather my belongings and slip back inside the cabin, following from the windows as the bear progresses onto the small, steep clearing between my cabin and another next door. Now in full sun, the bear pauses, sniffing the air and making a decision between my place and the neighboring cabin, a slightly larger one named Moonshadow, only a few yards away. I watch the bear lumber across the clipped grass and onto the Moonshadow porch. Four years ago, Greg and I married each other on that porch, surrounded by a small group of family and friends.

The bear launches up onto its hind legs, propping itself onto the porch railing, showing me its incredible size and height. It thunders back down onto the porch floorboards, only to rear up again, attacking the ostensibly bear-proof trash container (which my neighbors must have left unsecured). Violent, echoing clangs of metal and grunting follow, as the bear wrestles its prize from the bin, then spills the bag of trash across the porch and settles down, right across the front-door welcome mat, to feast.

Right there, four years ago, I swayed alongside my beloved aunt, my best friend, and my brand-new stepdaughter as Stevie Nicks conjured her deepest, wildest “Rhiannon” spells, and at that same moment an unexpected storm swept over the cabin, bending the trees around us in sudden gusts of wind while glimpses of sunlight shimmered through, raining gold.

The memory floods me as I watch the bear claim its place there. And at that moment, my poor neighbors arrive in their truck. Imagine their shock. These kind retirees, back from their vacation fun, to find this giant blocking their front door. From my window, I watch a futile standoff. It goes on and on, for the better part of an hour. The neighbors honk their horn. The bear does not even flinch. There is no hurry. And then, to my sudden discomfort, the neighbors give up. They drive away. And this is the moment when, for me, the experience begins to turn.

Already I begin to try out words for the story I will tell. As I watch and wait, the story starts to branch outward from the intimate core of present-time experience. It begins to expand, contract, shapeshift. It will learn the moods and habits of its audience, adapting its purpose, adapting me in the process. Already it gives me back to myself as a writer, yet again, as all stories-in-process do. Already it is rewilding me, feeding some necessary inward place, hungry and implacable, always within my nature.

They tell you to make noise when you encounter a black bear. They reassure you that bears wish to avoid humans and will scamper off when we show them our strange bluster. But this bear does not subscribe to our stories about it. It will sit down on your welcome mat and wait for you to leave. It knows that you will tell this story, and it knows that you will miss half of it, and more.

It knows that this is not a story about you.

***

In The Overstory’s final pages, one of the novel’s nine protagonists considers a particular word. Alongside other activists, he has helped to drag felled trees across a forest floor, arranging them to spell out this word in letters so large that they’ll be image-captured by satellites.

During this moment, his perception opens toward a wider, deeper understanding of what he sees and hears: “Already this word is greening. Already, the mosses surge over, the beetles and lichen and fungi turning the logs to soil. Already, seedlings root in the nurse logs’ crevices, nourished by the rot.”

I think I understand the human inhabitants of The Overstory. How their experiences of this deeper perception — even just a taste of this grander, richer knowledge of life’s interconnectedness — can overtake them. How they tend toward extremes in their efforts to protect a grove of old-growth redwoods under threat of destruction. I also understand how the characters are sometimes maddening, both to the other humans in their stories and to the humans reading their stories.

Some stories only work if they overrun their readers. Some stories are only worth telling if they overwhelm those who are willing to receive them.

[An online discussion about The Overstory with Emily Choate is archived here, and you can read more about the 50 Books/HT50 project here.]

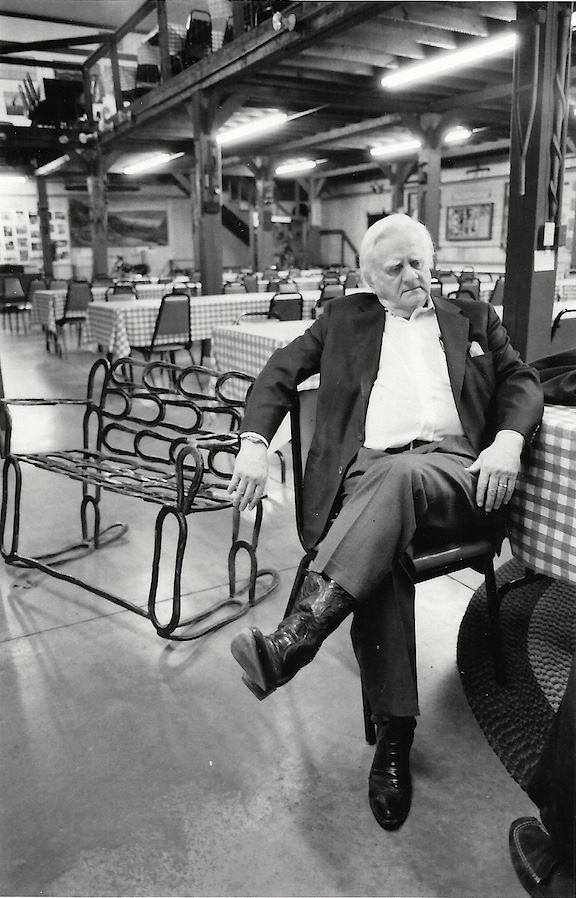

Emily Choate is the fiction editor of Peauxdunque Review and holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College. Her fiction and essays have appeared in Mississippi Review, storySouth, Shenandoah, The Florida Review, Rappahannock Review, Atticus Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and elsewhere. She lives near Nashville, where she’s working on a novel.