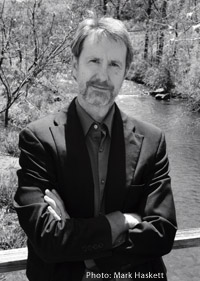

Bard of the Burdened South

Ron Rash chronicles the many troubles of the Appalachian poor

Not so long ago, Ron Rash was another critically-lauded-but-obscure regional writer whose small-scale stories, novels, and poems about the hard-luck lives of his Appalachian forbearers were cherished and revered by a loyal but limited audience. With his 2008 novel Serena, a Depression-era tale that chronicles the murderous power lust of a North Carolina timber baron’s wife, Rash leapt onto the bestseller and best-of-the-year lists from the left coast to the rarefied air of The New York Times. Serena’s success earned Rash comparison both to the great Southern stylists for his vivid, lyrical sentences and to the great social realists for his potent criticism of the excesses of unchecked capitalism and his acute consciousness of the synchronicity between mythic archetype and history.

With his new collection of short fiction, Burning Bright, Rash offers a scaled-down version of the same concerns, employing a sweeping cast of characters and historical milieus, ranging from the Civil War era to the present day. Though Rash stays firmly and almost exclusively rooted to Appalachian soil, the tales in Burning Bright argue persuasively that the most insistent and troubling human conflicts never change despite the passage of time or the ebb and flow of fortune.

With his new collection of short fiction, Burning Bright, Rash offers a scaled-down version of the same concerns, employing a sweeping cast of characters and historical milieus, ranging from the Civil War era to the present day. Though Rash stays firmly and almost exclusively rooted to Appalachian soil, the tales in Burning Bright argue persuasively that the most insistent and troubling human conflicts never change despite the passage of time or the ebb and flow of fortune.

Rash’s characters, bluntly speaking, are simple folks with real problems. Among his many gifts is the ability to make even the most hopelessly flawed characters endearing and the most senseless choices completely understandable (if not forgivable). These characters are driven by hungers of both physical and spiritual nature. In the collection’s first story, “Hard Times,” a farmer struggling to survive the darkest days of the Great Depression tries to deduce what or who has been filching eggs from his chicken coop, provoking first a shockingly violent encounter with his even less fortunate neighbor, and, later, a heartrending discovery.

In “Back of Beyond,” an amoral pawn shop owner stocks his store with stolen goods supplied by meth addicts—including the property of his own brother, stolen by his nephew. The shop owner reasons that if he didn’t buy the goods, his nephew would “just drive down to Sylva and sell it there.” But when he learns that his brother has been driven out of his own home by his son’s addiction, the shop owner can no longer avoid the inevitable moral reckoning. Rash ably and unflinchingly documents the physical and spiritual devastation wrought by the scourge of the crystal meth epidemic that continues to plague the rural South. In “The Ascent,” the child of meth addicts discovers the wreck of a small plane in the mountains high above his home, and the treasures he takes from the corpses of the pilot and passenger inevitably end up as fuel on the fire of his parents’ addiction.

What “burns bright” in these stories, it seems, is always some sort of need: the need for the next high; the need for love; as often as not, the need for money. And though Rash’s eye is drawn most persistently to the bleak dimensions of longing, Burning Bright is mercifully leavened with dark comedy. In “Dead Confederates,” two budding entrepreneurs look to get rich by pilfering uniform buttons and belt buckles from the graves of Civil War veterans to sell to memorabilia collectors. From the outset of the story, it’s clear that the plan will go awry: “Knowing a man for years and feeling hardly anything in his passing might make you think poorly of me, but the hard truth is had you known Wesley you’d probably feel the same,” the narrator dryly remarks. “You might do what I done—shovel dirt on him with not so much as a mumble of a prayer.”

What “burns bright” in these stories, it seems, is always some sort of need: the need for the next high; the need for love; as often as not, the need for money. And though Rash’s eye is drawn most persistently to the bleak dimensions of longing, Burning Bright is mercifully leavened with dark comedy. In “Dead Confederates,” two budding entrepreneurs look to get rich by pilfering uniform buttons and belt buckles from the graves of Civil War veterans to sell to memorabilia collectors. From the outset of the story, it’s clear that the plan will go awry: “Knowing a man for years and feeling hardly anything in his passing might make you think poorly of me, but the hard truth is had you known Wesley you’d probably feel the same,” the narrator dryly remarks. “You might do what I done—shovel dirt on him with not so much as a mumble of a prayer.”

In “Waiting for the End of the World,” Rash crafts a tribute to Lynyrd Skynyrd, back-road dive bars, and the temporary salve of booze and music to souls at the edge of ruin. It’s a story that simultaneously achieves near-slapstick absurdity and sublime, elegiac resonance. From his perch on a roadhouse stage, a disgraced English teacher-turned-cover-band front man mingles with a comic cast of similarly wrecked lives between renditions of “Free Bird” and meditations on the mixed blessings of the low-down life: “Such a lifestyle has its appeals,” the narrator muses. “One guy has his head on a table, eyes closed, vomit drooling from his mouth. Another pulls out his false teeth and clamps them on the ear of a gal at the next table. An immense woman in a purple jumpsuit is crying while another woman screams at her. And what I’m thinking is maybe it’s time to halt all human reproduction. Let God or evolution or whatever put us here in the first place start again from scratch, because this isn’t working.”

Ron Rash began his literary career as a poet, and many of these stories are, in essence, prose poems, emphasizing the correlation between the stark, isolate, unforgiving character of the eastern mountains and the thwarted but doggedly unyielding lives of Appalachian people. The people in Burning Bright always seem to hold on to hope, even when it seems to have abandoned them. In the title story, an aging widow falls in love and marries a young drifter, finding unexpected happiness in spite of the naked disapproval of her children and her community. But when an arsonist begins setting wildfires around the drought-stricken valleys of Western Carolina and suspicion falls on her husband, the woman retreats into denial: “She shut her closed eyes tighter, trying to open a space inside herself that might offer up all of what she feared and hoped for, brought forth with such fervor it could not help but be heard.”

In Burning Bright, the surprises are few; the problems Rash’s people face are predictable, as are their outcomes. The pleasures of this collection are found in the rhythms of Rash’s language, his penchant for haunting turns of phrase and incandescent images, and his deep and abiding compassion for even the lowliest of souls.

Ron Rash opens the 2010-11 Lipscomb University Landiss Lecture Series on October 28 at 7:30 p.m. in the Doris Swang Chapel of the Ezell Center on the Lipscomb University campus. A reception follows the program with a book signing. Admission is free.