Be Reconciled

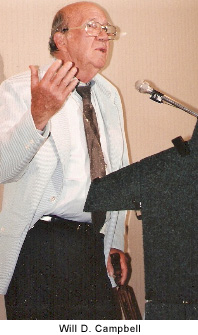

Remembering Will D. Campbell, author, preacher, and civil-rights activist

Two of Tennessee’s most senior nonfiction authors, Will D. Campbell and John Egerton, reached the close of a half-century of companionship this month when Campbell died from complications of a stroke on June 3, 2013. At a memorial service on June 22 at St. Stephen Catholic Community in Mt. Juliet, Tennessee, Egerton eulogized his friend and “fellow writer of rare books” with this remembrance:

If I go on too long, somebody say Amen.

On the second of August, 1965, I started to work for a magazine in Nashville. I had just turned thirty and moved with my wife and two children from Florida. The magazine was housed in a rambling old residence near the Peabody College campus, and my second-floor office, formerly a closet with a window, was barely big enough for a desk and chair, plus a second chair wedged into one corner.

On the second of August, 1965, I started to work for a magazine in Nashville. I had just turned thirty and moved with my wife and two children from Florida. The magazine was housed in a rambling old residence near the Peabody College campus, and my second-floor office, formerly a closet with a window, was barely big enough for a desk and chair, plus a second chair wedged into one corner.

I had met all my fellow staff members that morning and been given a warm welcome and my first assignment, which I was busily researching when the noon hour arrived. I heard a bump-bump-bump on the stairs just outside my doorway, and looked up to see a denim-clad, bespectacled man with a tumble of wavy locks dangling beneath the broad brim of a huge black hat. He stood there looking quizzically at me, whistling under his breath. I noticed that he was leaning on a carved walking cane, and one of his pants legs was canted into the top of a calf-high leather cowboy boot. I couldn’t keep from staring at the guy. He looked to be about sixty years old (he was, in fact, just forty-one), and mischievous, somehow, with the slightest hint of a sneer on his lips.

“You the new boy, huh?” he finally said, looking me over with what I felt was an air of disapproval. I stuttered an affirmative answer, and then he hit me again with another direct question:

“You cut hair?”

“Uh, well, no sir, I never have.”

“You’re not saying you can’t?”

“Uh, no sir, I just never have…. I guess I could, if I had to.”

He pulled the extra chair from the corner and put it in the doorway, facing out. Sitting down, he removed his hat and said over his shoulder, “You got some scissors in your desk, don’t you? All journalists got a pair of scissors.” I scrambled through the drawers and came up with the needed tool. “Just trim it around the back of my neck a little,” he directed. And so, within the next few minutes—before we had even exchanged names or the obligatory “Where you from?” line—I had become the new barber to Will Davis Campbell, and we had set out on a friendship that would last a lifetime.

Now he is gone, and many of you in this sanctuary today have come with stories of your own close encounters with Will, your own vivid memories of this extraordinary man. I have been given the grace, the unmerited privilege, to eulogize him, to gather up and spread good words over his ashes in behalf of us all, present and absent. I accept this assignment with trepidation and eagerness, with humility and confidence—hoping that what I have to say will resonate with all of you who knew him and loved him as I did. In particular, I pray that my words will be a balm to Brenda, Penny, Bonnie, Webb, and the grandchildren, and will vindicate their choice of me to join with Reverend Lawson and the others to speak and pray and sing our farewells to our beloved kinsman, friend, and brother.

Now he is gone, and many of you in this sanctuary today have come with stories of your own close encounters with Will, your own vivid memories of this extraordinary man. I have been given the grace, the unmerited privilege, to eulogize him, to gather up and spread good words over his ashes in behalf of us all, present and absent. I accept this assignment with trepidation and eagerness, with humility and confidence—hoping that what I have to say will resonate with all of you who knew him and loved him as I did. In particular, I pray that my words will be a balm to Brenda, Penny, Bonnie, Webb, and the grandchildren, and will vindicate their choice of me to join with Reverend Lawson and the others to speak and pray and sing our farewells to our beloved kinsman, friend, and brother.

For a long time after that first meeting, I puzzled over who Will Campbell really was—this funny, irreverent, sage, incisive, Mississippi country-boy cotton-picker-turned Yale Divinity scholar turned born-again Southerner-for-life. Before I met him, he had ricocheted from a Baptist pulpit to a university ministry to a diplomatic mission for the National Council of Churches in the South’s cauldron of racial strife. His last official station, beginning in 1965, was to be a cabin-based sinecure with a rag-tag remnant of Southern religious radicals whose interpretation of the biblical good news—“You are already forgiven”—sorely vexed the religious establishment, on the right and left.

The Committee of Southern Churchmen, as this shapeless clutch of activists called themselves, subsisted on private gifts and foundation grants—just enough to allow Will to carry on a personalized and individualistic ministry to black and white Southerners deeply scarred and disfigured by the centuries-old legacy of racial dehumanization.

I had only caught a fleeting glimpse of the “early” Will, who, it was said, drove a Mercedes and sipped chardonnay and wore tweeds and a Scottish cap and saddle oxfords, and smoked a pipe. The “new” Will, I now realize, was in the midst of a costume change that might make it easier for an avowed integrationist to “pass” in the tension-gripped South. The Campbells left their suburban three-bedroom ranch house for a Wilson County farm, and Will’s accoutrements soon became his insignias: outlandish hats and caps and canes, boots and blue jeans, chewing tobacco, whiskey, a tractor, a horse and a dog and a goat, an old pickup truck with a gun rack in the back window.

I had only caught a fleeting glimpse of the “early” Will, who, it was said, drove a Mercedes and sipped chardonnay and wore tweeds and a Scottish cap and saddle oxfords, and smoked a pipe. The “new” Will, I now realize, was in the midst of a costume change that might make it easier for an avowed integrationist to “pass” in the tension-gripped South. The Campbells left their suburban three-bedroom ranch house for a Wilson County farm, and Will’s accoutrements soon became his insignias: outlandish hats and caps and canes, boots and blue jeans, chewing tobacco, whiskey, a tractor, a horse and a dog and a goat, an old pickup truck with a gun rack in the back window.

But much more was in flux than these outside trappings. There was a fierce struggle going on inside his head. As the civil-rights movement came home to Nashville (school desegregation in 1957, the lunch-counter sit-ins in 1960, the freedom rides in 1961), Will could see that society’s pillar institutions—churches, schools, corporations, governments—did not have solutions to segregation and white supremacy; they were, in fact, central to the problem.

For four summers in the early 1960s, Will spoke at workshops for select groups of students from white and black colleges across the South. Seeing them as tomorrow’s leaders about to clash with an immoral power structure, he tried to hone for them a message of faith, fidelity, and endurance.

“Why are we here,” he asked rhetorically, “and what do we hope to accomplish? As I have gone from one racial crisis to another in the past five years, I have asked myself that question many times. I do not have an answer … but somewhere along the way, I began to feel the tragedy of the South, and I keep going because I have no choice under God but to behave as if the whole burden rests on my shoulders—knowing all the while that there is nothing that I have personally accomplished.”

He offered a parable about prehistoric tribes attacking one another, “not because they were dangerous or different, but just because they were there.” Will focused on a particular warrior who, returning from battle early one morning, saw a feather blowing along the beach and stooped to pick it up. It had no value, no practical use, but it was pretty, multicolored, soft—somehow, it spoke to his deepest feelings. He took it back to his cave, and when he showed it to others, its beauty seemed to blossom. “With that feather,” Will told the students, “civilization and human relations began.”

But, he went on, we haven’t changed all that much since then. “We still storm through the night at the other tribe—over vast oceans and narrow lunch counters, with H-bombs and lead pipes, and legislation and propaganda, and closed schoolhouses and burning buses…. Human relations begins with a point of view, a preconceived notion, a bias—but it can mature into … something much deeper. It really has to do with aesthetics … with what is true, just, pure, lovely, gracious. It’s [about] … our affair with the Almighty.”

After the last of those summer-workshop speeches in 1964, Will was still trying his dead-level best to be a faithful institutional Christian, but both he and the institution were loosening their grip. Finally, in August 1965—later in the month I first met him—he drove to Fairhope, Alabama, and to an epiphany that would mark his conversion.

Will’s brother Joe, struggling with the beasts of addiction, had gone to Fairhope to visit P.D. East, an iconoclastic ex-Mississippian and friend of the Campbell brothers. East, who had a rapier wit and an enviable way with words, had bought a little newspaper in the hamlet of Petal, near Hattiesburg, just as the magnolia veil of white supremacy was cracking open. Finding himself constantly in trouble, he finally was forced to flee with his family, but he took the Petal Paper with him, and published it irregularly from one place to another for a tiny but faithful underground audience of subscribers. Joe tracked him to Fairhope and then went there himself, taking his demons with him. Soon, P.D. called Will to come and help.

He arrived late in the afternoon, unaware of any breaking news, and found his friend and brother idly drinking beer under a shade tree.

“You know a fellow by the name of Jonathan Daniel?” P. D. casually asked. Will did know him—a gentle young seminarian from New England who had come to Alabama to help find a peaceful path to racial justice.

“Fellow named Tom Coleman blew him away with a shotgun this afternoon,” East reported. “Killed him dead.”

Will was devastated. Choking back tears, he got on the phone with people in the know—not church people, but journalists, lawyers, the ACLU, the Justice Department. Late into the night, the three men lingered at the kitchen table—eating, drinking, arguing. Inevitably, the talk turned to religion.

Will never forgot what happened next. “What do you reckon your friend Mr. Jesus thinks of all this killing?” P.D. asked him. Before Will could answer, P.D. challenged him to define the Christian faith. “What was Jesus all about, anyway? What was his message? Tell me that.”

Feeling wounded and defensive, Will sat stiffly, silently. Then he said, “We’re all bastards, but God loves us anyway.”

“Was Jonathan a bastard?” P.D. followed. Will hemmed and hawed, trying to duck the question, but finally conceded that, yes, even the beatific Jonathan was a bastard.

“And Tom Coleman too?”

“That’s easy. Yeah, sure,” Will replied.

P.D. closed in for the kill. “Which one of those bastards do you think your Mr. Jesus and his Daddy loves the most?”

In his superlative book, Brother to a Dragonfly, Will drew this story to a taut and painful climax. “Suddenly,” he wrote, “everything became clear. Everything. It was a revelation.” He began to whimper, to sob, and then to laugh: “I was laughing at myself, at twenty years of a ministry which had become, without my realizing it, a ministry of liberal sophistication … of looking for government to verify and authenticate our morality, of worshiping at the shrine of academia, of making an idol of the Supreme Court and a theology of law and order, denying not only the faith that I professed but my own history and my people—the Thomas Colemans: Loved [by God]. And if loved, forgiven. And if forgiven, reconciled.”

Later that fall, in the new quarterly journal of the Committee of Southern Churchmen, Katallagete (Greek for “be reconciled”), Will wrote: “When Thomas killed Jonathan, he committed a crime against the state of Alabama. Alabama, for reasons of its own, chose not to punish him for that crime. … When Thomas killed Jonathan he [also] committed a crime against God. The strange, the near maddening thing … is that both these offended parties have rendered the same verdict: … acquittal.”

This was the new Will Campbell, the road-to-Fairhope convert: the old Will in a different uniform, with a deeper and more complex understanding of the Southern/American/human predicament, the unspeakable tragedy of a world broken beyond our feeble ability to fix. And this was the Will I first met on that August day forty-eight years ago.

He was different, but familiar: a Southern character, a tangle of contradictions. He was a believer and a doubter. He saw through a glass, darkly, and wept for the victims and perpetrators of inhumanity. He heard the Jesus question in the Gospel of Matthew something like this: If you only love the ones who love you, what have you accomplished? Even the bankers and barkeeps do that much. No, that’s not enough. If you love one, you’ve got to love them all.

He was different, but familiar: a Southern character, a tangle of contradictions. He was a believer and a doubter. He saw through a glass, darkly, and wept for the victims and perpetrators of inhumanity. He heard the Jesus question in the Gospel of Matthew something like this: If you only love the ones who love you, what have you accomplished? Even the bankers and barkeeps do that much. No, that’s not enough. If you love one, you’ve got to love them all.

The new Will, like the old, knew in his heart that no matter what he did or how well he did it, it would never be enough. He was no saint. It wasn’t quite true that he loved everybody. He sometimes showed a vengeful impulse—a meekly devious, passive-aggressive tic. He boasted that he never voted for “the minions of Mr. Caesar,” but he lied—I saw him in line at his polling place, waiting for a ballot. His family was paramount—but not always primary. He was pretty much like the rest of us—maybe better at it, but still, he was just Will being Will.

What set him apart was this: he had an uncanny knack for reaching into people’s hearts, for making them feel they were important to him, they mattered. The poor, the homeless, the imprisoned, the untouchables felt that he cared about them. He earned the trust and respect of African American leaders in the South and nation at a time when trust was at a premium for anyone, anywhere. He was an ally of the working class—farmers, laborers, the service industry on whose shoulders all of us now rest. A host of religious people and non-believers, in and out of the steeples, drew inspiration from Brother Will. The music people embraced him, and he returned their love ten-fold. The scholars, lawyers, doctors—likewise. The word-and-picture people, we of the ink-and-paper trades, considered him a fellow addict. He belonged to us all, and we to him.

So we have come to this place, this time—and the last words are his. In his introduction to an unfinished book he was writing when he suffered the stroke that stole his verbal gift, Will Campbell offered this self-portrait:

I am a preacher. Of sorts. But I never made it big and never got famous in any traditionally ministerial endeavor, and I never kept a real job for very long. At least, not in the institutional world. I performed a score or so of marriages year by year, and about as many funerals. I visited hospitals and prisons and nursing homes, and a number of people regularly came by … to talk about one thing or another. They became my congregation, you might say. The professionals call that counseling. … I just called it visiting with friends and neighbors. I still do a fair amount of it. If you want to think of it as a scattered parish, a church without a steeple—and me as its pastor … tending the flock—that’s all right with me.

“Well, be about it,” he would be telling us, along about now. “Keep it in the yard. Yeah, pray. See you while ago.”

Somebody say Amen.

Copyright (c) 2013 by John Egerton. All rights reserved.