Beautiful Bible Stories

Sometimes the dearest childhood memento is a story

I was waiting for my mother to finish dressing my little sister in visiting clothes. Then we were going to walk to my neighbor’s house for a ride to school. I was five, and my mother was going to get me signed up for first grade.

But before we could leave, there was a knock on our door. Mom, assuming Miss Earlene had decided to pick us up instead, opened it. A man in a suit was standing on the step and holding a large case. My mother was not the sort to invite strangers inside, so I’m not sure how he made it into our house. But there he was, sitting on our sofa and telling my mother that he knew she was a good woman and, as a good woman, she would surely want to have the word of God in our home. A traveling Bible salesman had arrived at our door.

But before we could leave, there was a knock on our door. Mom, assuming Miss Earlene had decided to pick us up instead, opened it. A man in a suit was standing on the step and holding a large case. My mother was not the sort to invite strangers inside, so I’m not sure how he made it into our house. But there he was, sitting on our sofa and telling my mother that he knew she was a good woman and, as a good woman, she would surely want to have the word of God in our home. A traveling Bible salesman had arrived at our door.

The only thing I cared about was getting to school so I could see my classroom. But in my mind, looking back, I imagine him as something out of a Flannery O’Connor story, looking around the living room, pointedly noticing but not saying anything about the lack of a big family Bible on the coffee table.

Actually, we did have a Bible—a small white King James version that my mother had carried as part of her wedding bouquet. But it was more memento than holy book, kept in its own tiny box in my mother’s top dresser drawer. Even if my little sister and I wanted to read it, we would have had trouble with the tiny print and the whisper-thin pages that threatened to rip any time we even looked at them.

It became obvious to my mother that this salesman was not going to leave unless she bought something. There was just one problem: we were poor. Quite poor. And the only extra money she had at the moment was meant to buy my father a much-needed pair of work pants. The salesman might not have been so forceful if Daddy had been home, but my father worked the second shift at the factory, which meant that my mother was alone in her parenting and dependent on neighbors’ good will for appointments.

As the clock ticked nearer and nearer to the time when we were supposed to be at Miss Earlene’s, my mother grew more and more nervous. Finally, she agreed to buy a book. It was a wine-colored book of Bible stories for children. I’m guessing it was the least expensive offering. Still, my dad would have to wait another month for his pants.

As the clock ticked nearer and nearer to the time when we were supposed to be at Miss Earlene’s, my mother grew more and more nervous. Finally, she agreed to buy a book. It was a wine-colored book of Bible stories for children. I’m guessing it was the least expensive offering. Still, my dad would have to wait another month for his pants.

Over the years it became a family joke. “Good thing you didn’t split your pants. You’d had to cover your butt with a Bible story.” Of course, it wasn’t funny to my parents at the time. And the thought of a pushy salesperson guilting my mother into buying something she couldn’t afford still makes me angry.

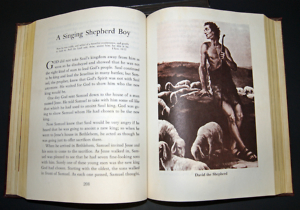

Mom handed the storybook off to me since I had a reputation for reading anything. But this wasn’t a children’s book in today’s terms. This was a book meant to be read by parents to their children. There was even a list of questions after each story for parents to ask. And the pictures were not illustrations but copies of paintings and wood drawings in museums: Da Vinci, Raphael, Bloch, and Rubens. They weren’t exactly fit for a children’s book: Abraham stopped just in time from stabbing a naked Isaac, Moses killing an Egyptian, and Jael driving a spike into Sisera’s head.

But despite the pictures, or perhaps because of them, I loved that book. It made the Bible seem much more exciting than my grandmother’s preacher did (although the latter was given to shouting in the middle of a sermon). Plus, Beautiful Bible Stories contained no references to the end of the world.

For some reason, that book didn’t disappear the way so many of my other storybooks did. I was not sentimental about my books once I had read them. I don’t really remember what happened to most of them, but when I moved out to go to college, there was no collection of books left behind, waiting to be given to my own hypothetical children. In some cases, I ruthlessly cut up old books to make school projects—my beautiful copy of A Child’s Garden of Verses became a fifth-grade poetry scrapbook. More likely, I simply read my books to death. They were cheaply made and didn’t hold up.

A few years ago, the daughter of a friend told me that she would have to give her American Girl dolls back to her older cousin when she was done with them. In all sincerity I asked why. She looked at me as if I didn’t have a lick of common sense and said, “So she can give them to her children.” Her response puzzled me as much my question irritated her.

There were no American Girl dolls in my childhood. There were very few hardbound books. Our toys were cheap, and we played with them until they died. It’s hard to build a collection of anything when four people are living in four rooms; you need most of your space just for living. And since we lived in rental houses until I was in junior high, it made sense to keep belongings to a minimum. We had no way of knowing how long we would be in any one house—at any time, a landlord could raise the rent, have a child leave a marriage and need a home, or decide it was less trouble to rent to the childless. There was always a sense that we had to be ready to move.

There were no American Girl dolls in my childhood. There were very few hardbound books. Our toys were cheap, and we played with them until they died. It’s hard to build a collection of anything when four people are living in four rooms; you need most of your space just for living. And since we lived in rental houses until I was in junior high, it made sense to keep belongings to a minimum. We had no way of knowing how long we would be in any one house—at any time, a landlord could raise the rent, have a child leave a marriage and need a home, or decide it was less trouble to rent to the childless. There was always a sense that we had to be ready to move.

So now the only memento I have from my childhood is Beautiful Bible Stories. It has been my companion for more than half a century. I probably haven’t looked at it since I was eight, but it has made every move with me from city to city, state to state. And it has survived the ritual culling I’m forced to do when my books overrun my bookshelves. I would swear I have no sentimental attachment to it. But I also know that when they clean out my room at the nursing home after my death, they’ll find it tucked away in one of the cupboards.

Copyright (c) 2016 by Faye Jones. All rights reserved. Faye Jones, dean of learning resources at Nashville State Community College, writes the Jolly Librarian blog for the college’s Mayfield Library. She earned her doctorate in nineteenth-century literature at Indiana University of Pennsylvania.