Before, When We Were Young

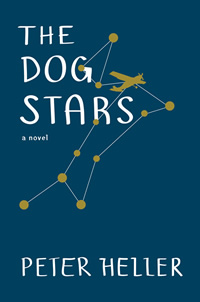

The past is a nightmare in Peter Heller’s terrifying, funny, heart-breaking, and suspenseful debut novel

“In the beginning there was Fear,” observes Hig, the hapless narrator of The Dog Stars, a new novel by award-winning adventure writer Peter Heller. Nine years earlier, an influenza epidemic decimated the population of the U.S.—and, presumably, the world—and Hig is one of the few survivors. Civilization has completely broken down, and the law of the land is now the law of the jungle. Hig, a contractor by trade and a writer by avocation, is still alive because he has a few things going for him. For instance, he can fly an airplane, and he has plenty of fuel. Also, he lives at a small county airport near Boulder, Colorado, that is equipped with wind and solar systems that continue to supply electricity, and it’s near a creek that provides fresh water. He has a beloved dog, Jasper, that serves as both an intruder-alert system and a hunting companion. Most importantly, though, Hig has Bangley, “a really mean gun nut” with his own arsenal, who also lives at the airport. Together they patrol an eight-mile radius around the airport, ruthlessly defending their position, because, as Hig explains, “The ones who are left are mostly Not Nice.”

Hig and Bangley’s only neighbors are a community of thirty Mennonites living on an old turkey farm ten miles south, infected with a mysterious blood disease that often followed the flu in those who survived, causing them to sicken and die slowly. Hig is not infected and tries to help the families when he can, delivering supplies and making repairs to their equipment. Bangley resents these charity trips because Hig’s absence weakens their defense and because he fears that Hig will carry the sickness back with him. In fact, Bangley resists any kind of “recreating,” and he considers that category to include “anything that didn’t directly involve our direct survival, or killing, or planning to kill which amounted to the same thing.” But Hig hates the fact that he is forced to kill to survive, and he needs to feel that he is helping someone: “Truth is I do it as much for me as them,” he explains to an uncomprehending Bangley. “It kinda loosens something inside me. That nearly froze up.” Hig also finds solace in the woods with Jasper, but too much has happened, too much lost, he believes, to allow him ever to recover any sense of true peace or happiness. “Grief is an element. It has its own cycle like the carbon cycle, the nitrogen. It never diminishes not ever. It passes in and out of everything.”

Hig and Bangley’s only neighbors are a community of thirty Mennonites living on an old turkey farm ten miles south, infected with a mysterious blood disease that often followed the flu in those who survived, causing them to sicken and die slowly. Hig is not infected and tries to help the families when he can, delivering supplies and making repairs to their equipment. Bangley resents these charity trips because Hig’s absence weakens their defense and because he fears that Hig will carry the sickness back with him. In fact, Bangley resists any kind of “recreating,” and he considers that category to include “anything that didn’t directly involve our direct survival, or killing, or planning to kill which amounted to the same thing.” But Hig hates the fact that he is forced to kill to survive, and he needs to feel that he is helping someone: “Truth is I do it as much for me as them,” he explains to an uncomprehending Bangley. “It kinda loosens something inside me. That nearly froze up.” Hig also finds solace in the woods with Jasper, but too much has happened, too much lost, he believes, to allow him ever to recover any sense of true peace or happiness. “Grief is an element. It has its own cycle like the carbon cycle, the nitrogen. It never diminishes not ever. It passes in and out of everything.”

Hig continues to grieve for his pregnant wife, Melissa, who died from the flu, and for their life together in Denver prior to the catastrophe. “Did you ever read the Bible? I mean sit down and read it like it was a book? Check out Lamentations. That’s where we’re at, pretty much. Pretty much lamenting. Pretty much pouring our hearts out like water.” An avid fisherman, he also mourns the trout that have died out because of climate changes: “If I ever woke up crying in the middle of a dream, and I’m not saying I did, it’s because the trout are gone every one. Brookies, rainbows, browns, cutthroats, cutbows, every one. … Didn’t cry until the last trout swam upriver looking for maybe cooler water.”

Flying over an abandoned cattle ranch, Hig pictures a scene that’s vastly different from the empty devastation he sees below him: “Squint and I can imagine someone in the yard. Someone leaning to bolt a spreader to the tractor. Someone thinking Damn back, still stiff. Smelling coffee from an open kitchen door. Someone else hanging laundry in a bright patch. Each with a litany of troubles and having no clue how blessed. Squint and remake the world.”

The ability to fly eventually uproots Hig and sends him far from the safe haven he and Bangley have created. On the heels of yet another painful loss, Hig decides to travel three hundred miles to the airport in Grand Junction, which he believes to be the origin of a faint radio broadcast he received several years earlier. He is haunted by the memory of the calm, professional voice of the air traffic controller—an echo of a time when the world made sense. The flight will take him past the point of no return—as a disbelieving Bangley points out, Hig won’t have enough fuel to return—but Hig is obsessed with the thought that someone else is out there, someone like him. Lacking any other purpose or meaning in his circumscribed life, he is determined to find the source of the voice and is willing to risk everything in the journey.

The ability to fly eventually uproots Hig and sends him far from the safe haven he and Bangley have created. On the heels of yet another painful loss, Hig decides to travel three hundred miles to the airport in Grand Junction, which he believes to be the origin of a faint radio broadcast he received several years earlier. He is haunted by the memory of the calm, professional voice of the air traffic controller—an echo of a time when the world made sense. The flight will take him past the point of no return—as a disbelieving Bangley points out, Hig won’t have enough fuel to return—but Hig is obsessed with the thought that someone else is out there, someone like him. Lacking any other purpose or meaning in his circumscribed life, he is determined to find the source of the voice and is willing to risk everything in the journey.

Heller paints a compelling picture of a post-apocalyptic landscape and the lengths to which Hig and Bangley must go in order to survive, but the warmth and authenticity of the characters prevent the material from becoming too bleak. Hig’s choppy, stream-of-consciousness narration requires close attention but also repays it, at times achieving a lovely, lyrical fluidity that perfectly expresses the tangled thought processes of a good but damaged man who has survived unfathomable tragedy yet continues to do his best to live according to the values he has been taught. “I set down the pack and breathed the smell of running water, of cold stone, of fir and spruce, like the sachets my mother used to keep in a sock drawer. I breathed and thanked something that was not exactly God, something that was still here. I could almost imagine that it was still before when we were young and many things still lived.”

In a starred review, Publishers Weekly called The Dog Stars “perhaps the world’s most poetic survival guide,” one that “reads as if Billy Collins had novelized one of George Romero’s zombie flicks.” This novel is terrifying, funny, heart-breaking, suspenseful, and surprising. Thanks to Peter Heller’s talent and vision, it will make you care what happens to this downtrodden but hopeful hero, his faithful dog, and his crazy friend, too.

Peter Heller will discuss The Dog Stars at the twenty-fourth annual Southern Festival of Books, held October 12-14 at Legislative Plaza in Nashville. All events are free and open to the public.