Beneath the Surface

Sara J. Henry’s second novel delves into the mysteries of a frozen landscape

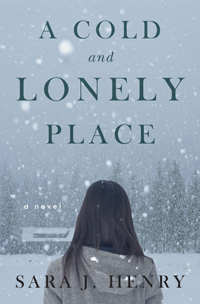

The Adirondack Mountains in winter. Deep snow. Winter sports. Cabins in the woods. Bodies in the ice. In Sara J. Henry’s second Troy Chance mystery, A Cold and Lonely Place, she brings the Lake Placid, New York, area to life with a story of family secrets, emotional and physical isolation, and sudden death. It is a landscape turned white and dangerous, a place “so cold that lakes freeze into solid masses that people walk on, cut holes in for ice-fishing, and drive sled-dog teams across,” as Henry’s narrator, a newspaper reporter, puts it. “It took my first long winter here to learn to gauge the weather and dress in layers so I wasn’t cold to the bone most of the time.”

Like many of the cold places on earth, the Lake Placid area—Saranac Lake in particular—stages a winter carnival featuring an ice palace: an ephemeral castle built of frozen blocks cut from the local lakes. Troy Chance is watching the ice-sawing crew one frigid afternoon when a shadow in the ice stops them. The shadow is a dead man whom Troy recognizes as Tobin Winslow, a recent arrival who had been dating one of her housemates. There is no evidence of foul play, and the police are left to ask general questions and wait on a toxicological report that may take days.

Like many of the cold places on earth, the Lake Placid area—Saranac Lake in particular—stages a winter carnival featuring an ice palace: an ephemeral castle built of frozen blocks cut from the local lakes. Troy Chance is watching the ice-sawing crew one frigid afternoon when a shadow in the ice stops them. The shadow is a dead man whom Troy recognizes as Tobin Winslow, a recent arrival who had been dating one of her housemates. There is no evidence of foul play, and the police are left to ask general questions and wait on a toxicological report that may take days.

Troy is a sports reporter for the local paper, and her editor asks her to do a little investigating, to tell the story of this young man’s interaction with the community, to learn how he came to live and die in such a frozen, isolated spot. It is an assignment that will lead to some difficult places. “I seemed to have a knack for finding out things,” Troy observes; “what I didn’t have was any clue how to handle the emotional fallout.”

Oak Ridge native Sara J. Henry won the Agatha, Anthony, and Mary Higgins Clark Awards with her first novel, Learning to Swim. That story of family tragedy introduced Troy, the Adirondack setting, and several recurring characters. Henry has lived in Lake Placid, too, working as a newspaper sports editor and owning a dog named Tiger, one of the recurring characters in her novels. But only her alter ego, Troy, solves mysteries involving the tangled lives of the local population. As Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes once observed, “the lowest and vilest alleys in London do not present a more dreadful record of sin than does the smiling and beautiful countryside.” Lake Placid is certainly a beautiful countryside. The rest is filled in by Sara J. Henry.

A Cold and Lonely Place tells an old-fashioned story of friendship, love, and mistrust set among the sometimes backbiting pettiness of small-town relationships. But as with all modern detective stories, technology provides a magnifying force, making everything that is easy easier and everything that is difficult even more so. Shortly after Tobin’s body is found, a libelous news story is spread far and wide via the Internet, hampering Troy’s research even as it begins. Soon she is dealing with Tobin’s generally anti-social girlfriend, his wealthy and determined sister, his eager-to-assist neighbor, and the memory of his dead older brother.

It’s a complicated group, and Troy begins to wonder whether her investigation into so many private matters, which brings her welcome accolades, is really helping the situation. She is a reporter with a conscience, who cares for the people she writes about. This empathy can be a weakness. “Sometimes,” Troy notes, “letting the truth out lets people heal, and sometimes it makes things worse. And you couldn’t really know which until you did it, and sometimes only later.”

It’s a complicated group, and Troy begins to wonder whether her investigation into so many private matters, which brings her welcome accolades, is really helping the situation. She is a reporter with a conscience, who cares for the people she writes about. This empathy can be a weakness. “Sometimes,” Troy notes, “letting the truth out lets people heal, and sometimes it makes things worse. And you couldn’t really know which until you did it, and sometimes only later.”

The dilemma Troy faces is a familiar question in the amateur-sleuth genre: how to decide which secrets need to be brought into the light and which are best left beneath the surface. The police typically must expose everything, but the amateur works independently of the law and has much greater discretion. If an investigation uncovers family sins, even sins that may help explain how a body came to be frozen in a lake in upstate New York, should the reporter announce them to the world from her perch on the worldwide web? And the fact that her subject is deceased makes Troy’s task more difficult. “Trying to figure out what dead people intended could drive you mad, especially when many people didn’t really know what they wanted even when they were alive.”

Yes, Troy does find herself in the middle of a delicate situation. Can she avoid making things worse? It all depends on what is going on in the lonely places, both in the world at large and inside the people who make their homes in the cold.

Sara J. Henry will launch A Cold and Lonely Place at Barnes & Noble Booksellers in Brentwood on February 5 at 7 p.m.