Beyond Domestic Fiction

There’s much more to Holly Goddard Jones’s stories than kitchen-sink realism

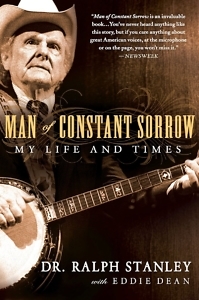

Nearly thirty years ago, Bobbie Ann Mason published her debut short story collection, Shiloh and Other Stories, a book filled with stories of working- and middle-class Kentuckians from suburban and rural towns, and the little earthquakes that shake their lives. (In the widely anthologized title story, a truck driver, out of work after an accident, begins to see his wife in a fresh and loving light, only to discover that she, in the process of discovering new possibilities for her own future, wants to leave him.) The book has since been canonized as an example of “kitchen sink realism”—the fiction of regional, blue-collar America.

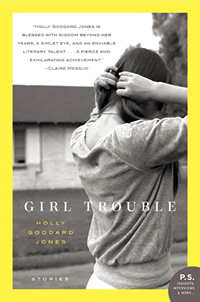

Fast-forward to 2009, when a new Kentucky girl, Holly Goddard Jones, made the literary scene with a much-praised debut collection of stories set in her home state. Jones is no Mason redux, but in Girl Trouble she does look carefully at the Kentucky in which she was raised, tapping into veins similar to those explored by Mason. Set in the fictional small town of Roma, these stories portray with deep sensitivity the emotional injuries of men and women whose lives are etched there. Marriages disintegrate, affairs are risked, friends are betrayed, memories fester. With an unflinching eye toward grief and loss, Jones reminds readers of the dramas that are played out every day in modest living rooms and kitchens, in seemingly sleepy and homogeneous suburbs. Girl Trouble is “poignant and approachable—ripe for any audience,” wrote a reviewer for the Las Vegas Weekly. “Jones could very well join the tradition of America’s great Southern writers.”

Prior to her appearance at Vanderbilt University on February 24, Jones answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: Eight stories, 322 pages—Girl Trouble is comprised of rather long short stories. What draws you to the longer story? Why not write a series of short novels instead?

Jones: I don’t think that I set out to make them a certain length—I just wrote until I thought I’d told the story. It takes me longer to do that than some other short story writers, I guess, because I like writing exposition. They’re not novel-length because I didn’t need even 200 pages to do what I wanted to do. The stories each focus on a single character, and there’s a psychological intensity to them that’s a bit much for novel-length.

Chapter 16: Do you see parallels between Bobbie Ann Mason’s work and yours?

Jones: Certainly Bobbie Ann Mason was an influence, a huge one. I talked about her influence when I spoke last April at the English Department awards ceremony at my alma mater [the University of Kentucky], and I was very embarrassed when I looked into the audience and saw that she was there. It was one of the more surreal moments in my life. Mason’s work gave me permission to write about home, even though I grew up thinking that my home wasn’t a very interesting place, or that it wouldn’t be interesting, at least, to anyone outside of it.

Jones: Certainly Bobbie Ann Mason was an influence, a huge one. I talked about her influence when I spoke last April at the English Department awards ceremony at my alma mater [the University of Kentucky], and I was very embarrassed when I looked into the audience and saw that she was there. It was one of the more surreal moments in my life. Mason’s work gave me permission to write about home, even though I grew up thinking that my home wasn’t a very interesting place, or that it wouldn’t be interesting, at least, to anyone outside of it.

When I started writing fiction, I was mimicking her stories—the movement of time, the voice, even the nature of conflict. When I was an undergraduate I wrote several stories about crumbling marriages that owed an embarrassing amount to Shiloh and Other Stories, and the characters even thought like Mason’s characters. It was that blatant. In grad school, I finally figured out some of what interested me, and it was a relief to me that my interests didn’t exactly overlap anymore with Mason’s, nor did my style. One big difference, I think—and I’m generalizing both our work in saying this—is that my characters tend to overthink their situations and to be very aware, at least on some level, of the nature of their problems. The exception in Girl Trouble is “Life Expectancy,” because Theo works hard to delude himself. Mason does more to externalize her characters’ changes in perspective, and the point-of-view character is oftentimes just an observer of change, not a participant.

Chapter 16: The length of the stories in Girl Trouble also brought to mind, for me at least, Alice Munro’s work—as did their subject matter and the handling of time. Like Munro, you often focus on the acute and lingering impact of events in your characters’ distant pasts. Whole lifetimes are covered in a single story. Why do you think you tend toward this narrative approach?

Jones: I like to think I’m still evolving as a writer, and what was true of the stories in that book might not always be true. When I wrote these stories, I think I was doing so partly in reaction to the fact that I just wasn’t very good at writing stories with compressed timelines. It seemed to be the dominant aesthetic, and I resented that, and I tend toward contrariness. So playing with layers of time and character histories was a way for me to stop writing bad Carver and Bobbie Ann Mason parodies. I don’t know if that will always be true for me. I’m working on a novel, but I’ve also written two new stories in the last year, and they’re doing different things. They’re longish, thirty-something pages, but they obviously don’t belong in the same book as Girl Trouble. And one takes place over a span of perhaps four or five hours’ time.

Chapter 16: All of the stories in Girl Trouble are set in the fictional small town of Roma, Kentucky. In what ways is the world of your childhood, your formative years, represented fictionally in the people and places of this book?

Jones: Roma is a lot like my hometown of Russellville. Switching the name gave me more room to invent when it suited me, and it seemed wise to me to distance the fictional events of the story from a real place. I didn’t want anyone to take the book too literally.

Jones: Roma is a lot like my hometown of Russellville. Switching the name gave me more room to invent when it suited me, and it seemed wise to me to distance the fictional events of the story from a real place. I didn’t want anyone to take the book too literally.

I was just in Italy this week to do some interviews in connection with an Italian translation of Girl Trouble, which is called Questa America, and the questions threw me—in a good way. I was being asked to explain how the stories represented America in just the way that I’ve been asked here to explain how the stories represent Kentucky, and I realized that sometimes my view in the book is really, really myopic. I believed that Kentucky was a certain way because my Kentucky had been a certain way.

Chapter 16: Can you say a little bit more about that? What was your Kentucky like, then?

Jones: Well, one of the Italian reporters observed that my characters were often very lonely and isolated. They had strong bonds within their core families, maybe, but they weren’t connected to a larger community. I think that he thought this was perhaps an American quality. What I realized, though, is that it’s probably not, nor is it a quality, exactly, of the town I grew up in. A lot of people back home bond through church, and I happened to not be part of a church-going family. My husband’s parents had friends that they socialized with regularly, and my parents did not, at least when I was a kid. My parents never spent time apart, and my mom has never gotten a driver’s license. Once, when I was in high school and bored, I asked my dad to take me to a movie, and he refused to do it, because he didn’t think it would be right to do anything like that without my mom and brothers. But then again, we didn’t do stuff like that as a family, either.

This all found its way into the book, even when I hadn’t meant for it to. The characters lead what may seem like these claustrophobic lives, but I never knew to think of them that way, even after I’d gotten married and left home and started living pretty differently myself.

Chapter 16: Is the novel you’re working on now also set in Kentucky? What does this work in progress look like?

Jones: It’s also set in Roma. It feels like a companion piece to the stories, whereas the new stories I’m writing feel as if they’re signaling the next phase of my writing life, whatever that turns out to be. I’m close to the end of the draft. I think I’ll be able to start revising it this summer.

Chapter 16: The recent success of Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom incited some heated discussion about the disparity in critical response to “domestic” fiction written by women and by men. As a woman writing stories that focus on the domestic, do you feel at all marginalized?

Jones: I realize that I’m going to sound obtuse saying this, but I’m honestly not even sure what domestic fiction means. I don’t know when a relationship story becomes a domestic story. Most stories are about relationships. What’s the other option—a work story? The problem, to me, is not that men’s domestic fiction is better respected. It’s that “domestic fiction” is just a code for “women’s literature,” whether the fiction being described is actually domestic or not. I mean, my book depicts two men acting out a rape and murder. Is that domestic? Is the story about the coach sleeping with his student, which takes place as much on the basketball court as it does in his home, domestic? Maybe they are, and that’s fine, but the term in that case seems too broad to be useful.

Chapter 16: On a related note, VIDA recently released some sobering 2010 statistics that confirm a continuing gender imbalance in publishing. As a successful writer and teacher—one who’s spent years in literary circles of one kind or another—do you think the statistics point to a real, concerning inequity?

Jones: Sure, of course. I can’t comment on this scientifically, and others have already pointed out that the numbers come at least in certain cases without what would be some helpful or illuminating context. Like, what was the female-to-male submission ratio? Or the number of books published by women versus the number published by men? But you can’t look at charts like some of those without admitting that there are some major inequalities. If men are out-submitting women two to one (and I’m not convinced that’s the case), why? What have female writers internalized about their abilities or their chances or even their sense of agency in putting themselves out there?

Chapter 16: What does teaching do for you as a fiction writer, and how are the students whom you teach different from the young writer you were at their age? Do you see any interesting trends in the work they’re producing?

Jones: Teaching has helped me to be more open and generous about fiction, more open to risk. I hadn’t realized all of the ways I subverted myself as a student until I saw those ways dramatized in my classroom. If I sneered at the work of a writer, it was usually because I didn’t understand what the writer was doing, and my lack of understanding made me insecure. If I clung too doggedly to what seemed to be my aesthetic—the aesthetic of the long, exposition-heavy short story, for instance—it was because, at least in part, I was hiding from some other area of weakness. We writing students can intellectualize what we do to the point that we lose the joy and spontaneity of creation. I’m still a very analytical teacher, but I try to encourage my students to take risks, and I can’t encourage them to do that without trying to take some risks myself.

Chapter 16: I’ve read some of your recent blog posts , and I really enjoyed them. You mention happily bidding adieu to the author photo that appears on your book and that once appeared on your website. What’s the story behind that picture?

Jones: First, I want to say that I think it’s a lovely photo, and the person who took it was a childhood friend. I look much better in that picture than I look in real life, and that was the point of it. When my stories were about to come out, my friend Morgan took all of these pictures of me that I could choose from for the various marketing materials. I was really excited! And I put up the best ones on Facebook, when I was still on Facebook, and people left me nice comments about them, which was of course why I put them on Facebook. The consensus was that the photo with the doors—and actually, I think it’s the one I sent to Vanderbilt for the poster—was the best of the group. My husband designed my website around it, and it was used in cropped form for the book, and it started to show up lots of places.

After a while, I just started to feel profoundly self-conscious about it. I felt embarrassed at the thought that someone would Google my name, and the first thing they’d see on my page was this blown-up photo of me. I mean, it started to feel like I was one of those real-estate agents who advertise on a park bench or something.

But it wasn’t just the photo. I felt like I’d started to speak in sound bites about my book, to the point that I lost a sense of connection with my words. Even though I’d believed in what I was saying at the start, I’d repeated myself enough times that my beliefs started to seem nonsensical or insincere. I don’t want to serve up more sound bites, but I’m not exactly sure what goes in their place.

Chapter 16: Your story “Parts” is about a mother in the years following her college-age daughter’s rape and murder—a truly horrific incident. The book’s final story, “Proof of God,” explores that incident from the killer’s point of view. How did these two stories came about? Which one came first?

Jones: I wrote “Parts” first. That story rose out of the initial and more immediately natural reaction that I have, and I think most of [us] have, when we hear about terrible crimes. We sympathize for the victim and the victim’s closest kin. “Parts” is a story about the aftermath of tragedy, but I also wanted to explore the why of a tragedy. The mother of the dead girl in “Parts” wonders why this happened to her daughter, but she could never know the true why, and probably never sympathize, with the person responsible for her loss. When she asks “why,” she’s asking it of God more than she is of her daughter’s killer, though she goes seeking something of that kind from Simon at the end of the story.

I think that, in real life, there’s probably no sufficient why to many crimes. But at least in some instances—and this is what I wanted “Proof of God” to explore—it seems to me that tragedy happens in part because circumstances line up in a certain fateful way, or because one person meets another person who brings out the worst in him. That’s more interesting to me than writing about a sociopath doing a sociopathic thing, though maybe the majority of people who commit violent crimes are just wired differently than the rest of us. I have no idea.

Holly Goddard Jones will read from her work in Buttrick Hall, Room 102, on the Vanderbilt University campus on February 24 at 7 p.m. The event is free and open to the public.