Big Enough to Block Out the Sun

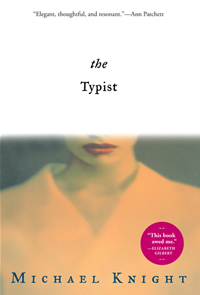

Michael Knight’s rich new novel The Typist is much more than the sum of its parts

At 185 pages, Michael Knight’s new novel, The Typist, could easily be considered a novella or even a long story—unsurprising, given that Knight has earned his greatest acclaim as an author of short stories. But despite its brevity, The Typist encompasses a variety of richly drawn characters, themes, and emotions typically associated with much longer, denser, more ostensibly “ambitious” novels. In this small book, Knight, who directs the creative-writing program at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, manages to veer through a variety of complications involving love, betrayal, black-market intrigue, and political maneuvering, all set against the backdrop of Japan’s national humiliation during the occupation years following World War II.

In Francis Vancleave, Knight has crafted an atypical narrator and protagonist for a war novel. Quiet and solitary by nature, Van has the mixed fortune of avoiding combat thanks to an unusual skill. As a boy, he learned to type from his mother, a former secretary who, Van confesses, would sometimes crawl into bed with her teenage son while Van’s father was away piloting a tugboat in and out of the Port of Mobile. “She’d curl up with her chest against my back, her knees in the crooks of mine, her hands pressed together, as if in prayer, between my shoulders,” Van recalls. “Our secrets: my typing lessons and her nights in my bed.” This subtle, striking memory reveals much about how Van earned his tender, pensive nature. “Though I quit church in the army,” he says, “I never did manage to shake what I would call a spiritual inclination.”

Van is assigned to the typing pool in General Douglas MacArthur’s Tokyo headquarters during the postwar occupation of Japan. His peculiar reserve contrasts markedly with the crude playfulness of Clifford, the Honor Guardsman with whom he bunks. Van is too shy to wear his war bride’s wedding band, but he nevertheless avoids the prostitutes and dance-hall girls of Tokyo. Clifford, in contrast, is a drinker and a brawler who falls for a beautiful department store model and becomes increasingly involved in nefarious black-market dealings to subsidize his love affair. Through Clifford, Van is drawn into both the seedy world of the Tokyo underground and the loftier company of MacArthur himself: as an Honor Guardsman, Clifford is able to finagle an afternoon for Van at the Great Man’s residence—a private screening of the Army-Navy football game.

Van is assigned to the typing pool in General Douglas MacArthur’s Tokyo headquarters during the postwar occupation of Japan. His peculiar reserve contrasts markedly with the crude playfulness of Clifford, the Honor Guardsman with whom he bunks. Van is too shy to wear his war bride’s wedding band, but he nevertheless avoids the prostitutes and dance-hall girls of Tokyo. Clifford, in contrast, is a drinker and a brawler who falls for a beautiful department store model and becomes increasingly involved in nefarious black-market dealings to subsidize his love affair. Through Clifford, Van is drawn into both the seedy world of the Tokyo underground and the loftier company of MacArthur himself: as an Honor Guardsman, Clifford is able to finagle an afternoon for Van at the Great Man’s residence—a private screening of the Army-Navy football game.

One of the many pleasures of The Typist is its sensitive, generous portrayal of Douglas MacArthur, second perhaps only to Patton in the category of larger-than-life American military leaders of the twentieth century. That Knight would feature one of U.S. military history’s most dashing figures as a prominent character in such a measured, unassuming context seems itself an act of admirable daring. MacArthur appears here at the peak of his glory, the midpoint between his flight from the Japanese invasion of Bataan and his controversial relief from command of UN forces in Korea by President Truman in 1951. Knight’s MacArthur is every bit the towering, near-mythic figure revered both by his troops and the Japanese for his benevolence and cultural sensitivity. But he is also “Bunny,” the beloved father figure who requires his Honor Guardsmen to send a weekly letter home to their wives or mothers, and who labors tirelessly to attend to the needs of his own family. Knight manages to show how the same qualities that underpin MacArthur’s determination to spare the people of Japan further disgrace also drive him to contrive for his boys an “all-star” game of American football and to give his own lonely son a companion.

Hence, Van finds himself in the unlikely position of playmate and mentor to young Arthur MacArthur, a boy poignantly torn between pride in his father’s stature and the awesome burden of being his son. Van does not yet know as he tells his story that, one day, young Arthur will change his name to escape the weight of his father’s reputation. But Michael Knight knows what will become of the boy Van first glimpses alone in a rowboat at the center of an enormous swimming pool, and his depictions of the sad child with his toy soldiers are drenched with pathos and apprehension. Arthur becomes a mirror for Van’s own melancholy and introversion—especially after Van receives stunning news from home that throws his future into turmoil. From the moment this news arrives, the personal and the political collide, as the lives of the characters each tumble toward tragedies small and large on the road back to Hiroshima, where MacArthur stages his football game as a sincere but achingly ill-chosen gesture of healing and reconciliation.

Critics have often remarked on Michael Knight’s economy of style, but terms like “compressed,” “economical,” and “minimalist” seem a disservice to such lyrical prose, which balances short, clipped sentences against longer, poetic passages with a grace and control reminiscent of Richard Ford and Tobias Wolff. Reflecting on MacArthur’s mission in Japan, Van explains, “I felt decent and important and part of something bigger than myself. Bunny had set the tone. We weren’t conquering these people, we were liberating them from centuries of tyranny. All of us were dimly aware that there were families living under railroad trestles somewhere in the city and that, because of food shortages, a letter from Bunny himself demanding that the War Department ‘send me more bread or send me more bullets’ had passed through the Officers Personnel Section, but none of that was our fault, the way we saw it, and it was hard to keep those things in mind at all when Emperor Hirohito was posing for photos in Bunny’s living room and the cherry trees in Hibiya Park looked exactly as they must have looked before the war and Little America was strung with Christmas lights in December and there were wreaths on all the lampposts and even the local entrepreneurs were selling holiday cards, woodcut prints of snowy mountains and brushy pines, the scenes beautiful and quiet, austere by comparison to the cards you bought back home.” This extended passage demonstrates how Knight creates tension with short sentences and then unloads a flood of confusion, irony, and inner conflict through the streaming, rambling observations of his narrator. It’s a masterful execution of symbiosis between content and form. Knight’s use of the conjunction “and” also calls to mind Ernest Hemingway, and the precise, understated quality of The Typist as a whole is a fine example of Hemingway’s belief that “the dignity of movement of an iceberg is due to only one ninth of it being above water.”

Critics have often remarked on Michael Knight’s economy of style, but terms like “compressed,” “economical,” and “minimalist” seem a disservice to such lyrical prose, which balances short, clipped sentences against longer, poetic passages with a grace and control reminiscent of Richard Ford and Tobias Wolff. Reflecting on MacArthur’s mission in Japan, Van explains, “I felt decent and important and part of something bigger than myself. Bunny had set the tone. We weren’t conquering these people, we were liberating them from centuries of tyranny. All of us were dimly aware that there were families living under railroad trestles somewhere in the city and that, because of food shortages, a letter from Bunny himself demanding that the War Department ‘send me more bread or send me more bullets’ had passed through the Officers Personnel Section, but none of that was our fault, the way we saw it, and it was hard to keep those things in mind at all when Emperor Hirohito was posing for photos in Bunny’s living room and the cherry trees in Hibiya Park looked exactly as they must have looked before the war and Little America was strung with Christmas lights in December and there were wreaths on all the lampposts and even the local entrepreneurs were selling holiday cards, woodcut prints of snowy mountains and brushy pines, the scenes beautiful and quiet, austere by comparison to the cards you bought back home.” This extended passage demonstrates how Knight creates tension with short sentences and then unloads a flood of confusion, irony, and inner conflict through the streaming, rambling observations of his narrator. It’s a masterful execution of symbiosis between content and form. Knight’s use of the conjunction “and” also calls to mind Ernest Hemingway, and the precise, understated quality of The Typist as a whole is a fine example of Hemingway’s belief that “the dignity of movement of an iceberg is due to only one ninth of it being above water.”

In an age when attention spans are diminishing by the second and few readers have the patience for literary epics, Michael Knight has delivered a book that achieves in an astonishingly compressed form all the artistry, depth, and seriousness of a thousand-page doorstop of a war novel. The Typist is a fine addition to the catalogue of World War II novels, capturing an often overlooked facet of the war. But it chiefly deserves attention and admiration for proving effectively that a book need not be long to be big.

[This review originally appeared on August 19, 2010.]