Book Excerpt: Madison Smartt Bell’s The Color of Night

In the aftermath of 9/11, not everyone is weeping

[In his new novel, The Color of Night, Madison Smartt Bell takes readers into the mind of Mae, a woman who has channeled the incestuous abuse of her childhood into a mystical, eroticized obsession with violence and death. Televised images of the 9/11 attacks thrill her, spurring memories of a sojourn with a Manson-like cult and of a woman, Laurel, who was her lover and ally there. The following numbered sections are selected chapters from the forthcoming novel The Color of Night by Madison Smartt Bell.]

1

Until the day the towers fell, I’d long believed that all the gods were dead. For years, for decades, my head was still. Only sometimes, deep in the desert, the soughing ghost voice of O-. But still, the bell of my head was silent, swinging aimlessly over the void.

I could watch it again, as much as I wanted, since the TV kept playing it over and over like a game of Tetras no could win. No limit to how many times I could consume, could devour those images. Again and again the rapid swelling, ripening to the bursting point, and then the fall. The buckling, crumbling, blooming outward in that great orb of ruin before it showered all its matter to the ground. Those gnat-like specks that swirled around it proved to be mortals, springing out of the flames. Wrapped in the shrouds of their screaming, they sailed down.

It didn’t matter how many saw one watching, since none can know another’s heart or mind. I had not known my blood could rise like that. Still, again, despite the years, the withering of my body.

Sometimes the television showed a plane biting into the side of a building, its teeth on its underside where the mouth of a shark is—then flame leaped up from the wound like the red surge from an artery. Then there were shots of living mortals on the street, wailing, raking the flesh from the bone of their faces, or some of them frozen, prostrate with awe.

So I saw Laurel for the first time again, Laurel kneeling on the sidewalk, her head thrown back, her hands stretched out with the fingers crooked, as weapons or in praise. Blood was running from the corners of her mouth, like in the old days, though not for the same reason.

3

The trailer park was shut up tight with chain link fence, but I had broken some of the links with a bolt cutter, right behind my tiny deck, so I could walk directly into the desert when I pleased. When I went through I pressed my palm against the jagged ends of the cut wire, not quite hard enough to break the skin, and then I pulled the pieces back together so the tear in the fence wouldn’t be too obvious, in case anyone were to look, which no one would.

As the owl struck silently, out of my sight, some rodent uttered a desperate shriek—piercing, but it didn’t last long.

In one of the trailers behind me a television was muttering and in another an old woman wept, in harsh, ugly, choking sobs. I walked until these sounds disappeared, holding my back to the spangle of lights in Boulder City. I could hear only my own rubber soles crunching on the pale dust of the desert, and that not much, for I walked very softly. Sometimes I took the rifle and didn’t kill anything. Tonight I had left the rifle behind and I was empty-handed.

I crossed fat tracks of an ATV in the sand, and further south the string of S S S left by a sidewinder. No sign of the snake itself. The desert looked flat and empty as the moon. The moon, the real one, had not risen. Selene had not stepped into her car.

The stars were cold and far away and I stood under them with my knees slightly bent and my back to the desert wind, which rushed through my legs and the sleeves of my shirt and dragged my dark hair forward around my face. Ambient light from Las Vegas bled into the sky from the north and dimmed the stars. Rage. Rage. It grew and then faded.

The wind fell then and as it died a great owl stooped across my left shoulder, in a perfect silence that thrilled down my spine through the soles of my feet into the sand. As the owl struck silently, out of my sight, some rodent uttered a desperate shriek—piercing, but it didn’t last long.

There. That would do. But I remained, still where I stood for a few minutes longer. I curled my fingers into my palm, feeling an edge of nail against the skin. I would need to cut my fingernails before tomorrow. I keep them short.

The stillness surrounding me was not quite perfect; I could still hear the drone of cars on a highway somewhere, and maybe, on some distant ridge, white turbines of a wind farm. The wind returned, fitfully now, bringing a soughing sound as it dragged across some cavity, a set of lips, a hole. As sometimes happened, I seemed to hear O-‘s voice singing in the space between the stars

…. ταύρος -ταύρος-χορν’δ και thro “η κατάθλιψη της νύχτας. Με τα αστέρια που περιβάλλονται, και με το φανό της ευρείας…

fitfully too, intermittent, senseless. Or I would not admit the sense

…ο του οποίου ηλέκτρινος σφαίρα κάνει το απεικονισμένο μεσημέρι της νύχτας:

the longing, the eternal sadness, vexed me. The sonority of his meaninglessness

…Εραστής των αλόγων, θαυμάσιος…

But of course it was only the wind after all. Or it least it stopped, before my heart turned completely black.

The wind switched direction, bringing grit into the corners of my eyes. I turned away from it, toward the vacant glitter of the town. Soon dawn would come. Fatigue was a grey square in my brain, between my eyes. I might almost be tired enough to sleep.

When I came back inside the trailer I cast about till I found my nail clippers, their cheap metal silver in the first thin light of the morning. I tore open a pack of jerky for breakfast, and without thinking about it I snapped on the television and there it all was. A hole in the world. Through the fissure of the TV screen it all came washing over me.

11

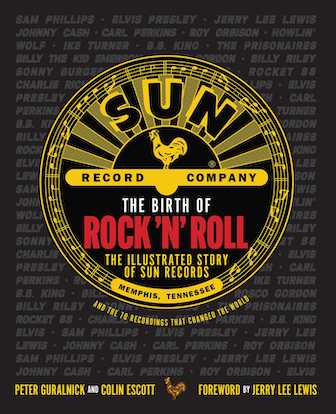

I still had all of O-‘s old records, though probably most of them were scratched. His pictures on the jackets wrinkled with old spills. In the fold of a double album I found a couple of thirty-year-old pot seeds.

It had all come out on CD, of course, the instant they invented them. You could, I could, download them to your i-Pod or whatever.

I didn’t try to listen to the records, in part because I didn’t own a turntable any more. I did slide one of the platters out, to look at the oily black surface. A puff of powdery cigarette ash came out of the sleeve ahead of the disc. A pale curved gash lay across the grooves of the first three tracks.

As for the music of Orpheus, it was balm to everyone’s wound. Your broken bones began to knit together when you heard it. Everyone turned toward it, like grass turns toward the sun.

When I pushed the record back into the jacket, my eye lingered on something it had skimmed a thousand times before. Snaps from the recording session were printed on the cover, laid out in an artificially casual fashion, as if they’d fallen on the floor. There was O- in the spring of his youth, an acoustic guitar balanced on one knee, looking with smiling, lively interest at something beyond the right edge of the frame.

The thing I hadn’t previously attended to was a foot, down in the lower right-hand corner of the snapshot. A nicely shaped young foot with a high graceful arch, nail-polish of such a dark crimson it was almost black, a gold-colored toe ring, and one of those higgledy-piggledy patterns Laurel used to draw on herself with henna back then.

Now there was a woman ahead of her time. I don’t know how I’d never noticed that before.

As for the music of Orpheus, it was balm to everyone’s wound. Your broken bones began to knit together when you heard it. Everyone turned toward it, like grass turns toward the sun.

28

Ursa Major clambered up the ink-black sky, casting cold light on the alkaline desert floor. I had walked a long way, far enough that the stains of city light had faded to sulfurous blooms on the horizon at my back. Ahead, the faint ribbon of a jackrabbit trail, packed to a just slightly paler shade than the loose sand surrounding it, wavered into a tumble of boulders that spilled down from the mesa there.

I crouched on my heels, beside a gnarl of juniper, clenching its dry roots into cracks of one great stone. The shadow of the bush fell over me, covering me with the dark.

High on the mesa, coyotes sang. The wild, high, half-hysterical crying sound. Sound carries strangely in the desert, so they might in fact have been miles away, and there might have been no more than a pair of them, though it sounded like a chorus of a dozen or more.

I watched for rabbits; there were none. Time passed, while overhead the stars kept turning, with that faint, scarcely audible music, as when you rub your spit-wet finger round the rim of a crystal glass.

Maybe the coyote could see me in my hood of shadow. Maybe he could smell the blood, pumping the long circuit from my heart.

The coyotes had stopped their concert long before. But now one came cautiously along the jack rabbit trail, out of the boulders, all covered with those clinging knots of juniper. Skulking, pausing often to hump up his back and turn his muzzle over his shoulder. Then with his ears rotating forward, pricked, he advanced again, with a spring in his step and a sharpening attention on the surface of the trail, though there was nothing to stalk that I could see, no rabbits, not a lizard, mouse or squirrel.

Maybe the coyote could see me in my hood of shadow. Maybe he could smell the blood, pumping the long circuit from my heart.

I stood up, clear of the shadow, making myself large. The coyote balked, cringing backward on folding knees, ears flat back to the fur of the head. His eyes pale globes of yellow, under the weak starlight.

Tonight I hadn’t brought the rifle. The coyote and I remained in a frozen balance. Eventually I took few slow backward steps; the coyote stayed right where he was.

I turned away and walked, not quickly, feeling a pale spot on my spine, though I knew very well a lone coyote would not attack a full-grown person, unless rabid, and this one showed no sign of that. Even that possibility was nothing to me.

Behind me, just possibly, dry whisper of paws on the sand. When I looked back the coyote was still motionless.

Again. Next time I looked, the coyote’s distance from the boulder might have changed a little. He was still.

Next time I looked I’d walked a mile or more and was near enough to the trailer park to pick out individual points of light from the blur. The coyote came loping after me now, but at a considerable distance on my back-trail.

I went on slowly, toward the artificial lights, thinking of how the first wild dogs must have come into camps, for whatever reason, to enslave themselves to men. When I reached the tear in the chain link fence, the coyote was nowhere to be seen.

(0)

(0)

(0)

The round open wound of emptiness….

Careless, I’d scraped my forearm going through the fence; blood beaded and absently I licked it clean as I climbed the wooden steps of my back deck. The thick salt taste at the back of my throat. I wasn’t hungry, thirsty, sleepy. There were still hours of night yet to pass.

I sprayed antiseptic on my arm; the sting of it barely seemed to reach me. Somehow the wireless phone was in my hand. For a second time I dialed the New York number.

“Hello…”

(0)

“Hello?”

Oh, I could certainly picture her then; I didn’t need to watch the tape. On her knees with her head flung back, heavy breasts lifting through the cloth, crooked fingers clutching the sparkling dust-filled air.

“Mae,” Laurel’s voice burrowed in my ear. “Mae?”

I never gave her the penny, I thought. That was what I thought I wanted to say. But my lips were sealed, as if copper had been laid upon them, and my eyes were heavy under metal weight.

I didn’t come to for a long time after, finally waking to scorched daylight, phone in my limp hand again, the robot voice advising me if you would like to make a call to hang it up.

36

I took the rifle into the desert and waited by the rabbit trail, crouched in the shadow of a boulder. No rabbits. No water. In my dry mouth I held a stone.

I could hear mice moving but I couldn’t see them, which was strange when the color of night was so pale. There was a moon, and the desert floor curved away from its sere light, like a moonscape reflected. Dark spines of yucca probed out of the cracks among white rocks. Toward the horizon, a switch of broom grass and the twisted branches of mesquite reaching wraithlike into the sky.

A scent of the smoke of blood sacrifice, rising between the horns of the altar. Horns of the moon.

Presently a coyote came, hunting mice—quick and alert as a cat, fixing invisible prey with his eyes and then pouncing. I raised the rifle and found him in the scope. The coyote turned his head toward me. Ears up, poised. All his being focused on the shadow of the rock where surely he must know I was.

We balanced there, for a long time. I held him in the crosshairs until dawn, and let him go.

39

Pauley’s rifle came in a long rectangular case like a guitar, with plush-lined compartments for the rifle itself and for the scope and the Starlite attachment and for the silencer, a big awkward thing, the size of a wine bottle. Out in the desert there was no one to hear, but one night I took the silencer with me, just the same.

It didn’t weigh a quarter as much as a wine bottle, but it did change the balance of the weapon. I practiced till I’d adjusted to the difference, finding targets, but not firing. A point of stone or a fallen branch. Things already dead. That never lived.

To reach out with an invisible silent fatal touch….

Then, movement. In the scope a flicker of phosphorescent green.

Then, movement. In the scope a flicker of phosphorescent green. With the silencer the shot made scarcely any more sound than a sneeze, or the sound of someone spitting on dry sand. I made myself prop the rifle carefully upright against a stone before I fell on the coyote, my blade drawn. Coyote still kicking spasmodically, scuffing fine gravel with his claws. The dead jaws snapping.

Gutted it. Skinned it. As Terrell had taught me all those years ago, when we used to go out together to hunt deer. The knife I had now was not the best I had ever owned, and was getting dull by the time I got to the difficult part. I sharpened it against a stone, resumed the flaying. At last the head skin came off whole. I stopped, on my knees, propped up on my palms, panting like a dog.

Blood to my elbows. In the weak starlight, against the pale floor of the desert, it looked black. The sound of my breath like a rasp on dry wood.

I stood up slowly, raising the limp skin by its shoulders, and looked into the vacant eye holes of the god mask. Presence in absence. The unavoidable fixed stare. If the features seemed to shiver it must have been because my hands were slightly trembling. The smile now curling fondly at the corners, peeled from its bloodstained teeth, which lay near me on the ground. At my feet the carcass was now still, wronged and irreparable, leaching its sticky fluids into the sand.

Facing the hum of light pollution on the horizon, I raised the skin above my head. Rank smell of musk and blood surrounding me now. Limp mask dangling before my face. I did not want the skin to touch me this time, to settle on my shoulders like a mantle. Awkwardly I held it up, over and away from me, balancing and aligning. To look back, through the eyes of the beast, at the dying glow of the mortal world.

To read an interview with Madison Smartt Bell, click here.

Copyright (c) 2011 by Madison Smartt Bell. All rights reserved.