Breakout Fiction

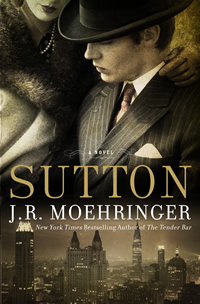

Bank robber, folk hero, and prolific prison escapee, Willie Sutton is the inspiration for the first novel by bestselling memoirist J.R. Moehringer

It’s no wonder J.R. Moehringer won the 2000 Pulitzer Prize for feature writing as a reporter with The Los Angeles Times. His first book, 2005’s New York Times bestselling The Tender Bar, is as captivating a memoir as any reader could hope for—so much so that retired tennis star Andre Agassi asked Moehringer to collaborate with him. The result was 2009’s bestselling Open.

But Moehringer has always said he wanted to write a novel, and it’s fitting that his first is a work of historical fiction based on the life of William “Willie” Sutton, whose hardships as an Irish-American kid in Brooklyn during the Depression led to a four-decade-long criminal career. “Willie the Actor” was a pacifist bank robber known for using disguises. Though Sutton is a work of Moehringer’s imagination, it also hangs on reams of fascinating research into the life and career of this American folk hero.

Moehringer recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email in advance of his appearance at the Southern Festival of Books, to be held in Nashville October 12-14.

Chapter 16: You were recently quoted as saying you became a journalist because you couldn’t figure out how to become a novelist. Now that you are a novelist, how would you characterize the process of writing Sutton as compared with the two bestselling memoirs you’ve written?

Moehringer: I decided early on that I’d have to use old habits to acquire new skills. So I approached Sutton first as a journalist. I dove headlong into the subject, spent months reading, traveling, doing interviews, just as if I was writing a profile of the bank robber. Then, like a memoirist, or a ghostwriter, I sat quietly with all that raw material, stewed over it for a long time, trying to channel my protagonist, to hear his voice, to get a feel for his heart and the through-lines of his narrative. Finally I let myself write as a novelist, meaning I let my imagination off the leash.

Moehringer: I decided early on that I’d have to use old habits to acquire new skills. So I approached Sutton first as a journalist. I dove headlong into the subject, spent months reading, traveling, doing interviews, just as if I was writing a profile of the bank robber. Then, like a memoirist, or a ghostwriter, I sat quietly with all that raw material, stewed over it for a long time, trying to channel my protagonist, to hear his voice, to get a feel for his heart and the through-lines of his narrative. Finally I let myself write as a novelist, meaning I let my imagination off the leash.

Chapter 16: You’ve said you’ve been captivated by Sutton since boyhood. What sparked your interest?

Moehringer: As a kid I was struck, and vaguely alarmed, that this hardcore criminal was the toast of New York. I kept thinking, Why is this man so brazen? Why is he not in jail? Also, I found it confusing that the mention of Sutton’s name often elicited a wry smile from the adults around me. Then, in 2008 and 2009, I felt a similar alarm and confusion about the bankers who caused the global financial crash. I found myself asking the same questions—Why are these men so brazen? Why are they not in jail?—while noting that no one ever smiled, wryly or otherwise, at the mention of the bankers’ names. So I wanted to explore the similarities and differences between people who rob banks and bankers who rob people. Turns out, Sutton is a much more likeable, sympathetic figure than any of the bankers who caused the crash. He certainly hurt fewer people.

Chapter 16: Given your exhaustive research into Willie Sutton’s criminal history, combing New York City Police Department and FBI records and interviewing his family and acquaintances, did this project feel as creatively liberating as you might have imagined writing a novel to be?

Moehringer: I did feel constrained at times by certain stubborn facts. But maybe a novelist is always constrained by something. Even characters you invent from whole cloth have limits, boundaries, parameters. There are always things your characters wouldn’t say, or do, no matter how much you might want them to. Structure, point of view, past tense, present tense—every choice you make as a novelist creates some degree of constraint because it precludes other choices. Working within constraints, but staying free and flowing creatively, seems like a big part of the whole task of writing a novel.

Moehringer: I did feel constrained at times by certain stubborn facts. But maybe a novelist is always constrained by something. Even characters you invent from whole cloth have limits, boundaries, parameters. There are always things your characters wouldn’t say, or do, no matter how much you might want them to. Structure, point of view, past tense, present tense—every choice you make as a novelist creates some degree of constraint because it precludes other choices. Working within constraints, but staying free and flowing creatively, seems like a big part of the whole task of writing a novel.

Chapter 16: You’ve characterized Sutton as the “Gandhi of gangsters.” If you could meet him at Dickens, the neighborhood bar that was so influential during your childhood, what’s the first question you’d ask him?

Moehringer: I’d ask him to read my novel and tell me what I got wrong.

Chapter 16: Sutton, you’ve noted, was a serious intellectual in addition to being a prolific thief. In your imagining of him, is there a deep philosophical underpinning to his career in crime, or are the two elements of his personality completely separate?

Moehringer: Many things drove him, but intellectually it wasn’t philosophy so much as it was esthetics. By all accounts Sutton was a serious reader, and by my reckoning he was also a frustrated writer, and I think he channeled his artistic, literary urges into his crimes. He went about robbing a bank, or escaping a prison, with the idea that it could be done with real artistry and craftsmanship. In one of his memoirs he even referred to his last prison break as his “masterpiece.” Maybe that’s why he fascinated so many writers, from Pete Hamill to Saul Bellow.

Chapter 16: What can we expect from you next? Do you think you’ll ever venture back into a traditional newspaper role again?

Moehringer: I love newspapers, so I’d never close that door. But right now my focus is magazines and books. I have an idea for the next novel, but it’s too early to talk about. It’s in the planning stage. I’m casing it, like a bank.

J.R. Moehringer will discuss Sutton at Nashville’s Southern Festival of Books on October 13 at 1 p.m. in the Nashville Public Library Auditorium. All festival events are free and open to the public.