Celebrating the Wide Embrace

Poet Jesse Graves considers the life and literary achievements of Jeff Daniel Marion

I knew the name, the reputation, and the poetry of Jeff Daniel Marion long before I had the occasion to meet the man himself. As an undergraduate at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville during the mid-1990s, I was immersed in a vibrant literary community on campus, with inspiring poetry teachers like Connie Jordan Green, Marilyn Kallet, and Arthur Smith and classmates like Heather Dobbins, Charlotte Pence, Melissa Range, Daniel Roop, and Jennifer Vasil, who were not only wonderful poets, but also great friends. I saw readings by legendary poets such as Galway Kinnell and Linda Gregg. But Knoxville’s literary life didn’t end at the edge of campus, and a name that came up again and again in bookstore circles and the local papers was Jeff Daniel Marion. I had no idea yet that the same widely regarded poet I was hearing about would someday become one of my closest and most treasured friends and mentors, Danny Marion.

I spent many afternoons during those days in bookstores, searching the shelves for names I had heard in literature classes and looking for interesting titles that could become my own discoveries. My favorite used bookstore was a hideaway in the back of Jackson Avenue Antique Mall in Knoxville’s Old City, which later became the Book Eddy and is now Central Street Books. I would browse for hours, self-educating, as former Poet Laureate Ted Kooser says all poets must do. I recall opening one nicely bound paperback with a striking hourglass image on the cover and finding on the inside flap, in the most distinct handwriting, the name “Jeff Daniel Marion, 1969.” This date was almost a decade before Marion’s first poetry collection, Out in the Country, Back Home, was published. The book was Alfred Kazin’s essay collection Contemporaries, and though I had no idea who Alfred Kazin was, I knew that if Jeff Daniel Marion, about whom I had heard so much, had read this book once, then I needed to buy it and do the same. I was delighted to find an essay titled “Good-by to James Agee.” James Agee had already become one of my local heroes, but I still find it a lovely happenstance that a book once owned by East Tennessee’s greatest poet led me to a classic essay about East Tennessee’s greatest prose writer.

I spent many afternoons during those days in bookstores, searching the shelves for names I had heard in literature classes and looking for interesting titles that could become my own discoveries. My favorite used bookstore was a hideaway in the back of Jackson Avenue Antique Mall in Knoxville’s Old City, which later became the Book Eddy and is now Central Street Books. I would browse for hours, self-educating, as former Poet Laureate Ted Kooser says all poets must do. I recall opening one nicely bound paperback with a striking hourglass image on the cover and finding on the inside flap, in the most distinct handwriting, the name “Jeff Daniel Marion, 1969.” This date was almost a decade before Marion’s first poetry collection, Out in the Country, Back Home, was published. The book was Alfred Kazin’s essay collection Contemporaries, and though I had no idea who Alfred Kazin was, I knew that if Jeff Daniel Marion, about whom I had heard so much, had read this book once, then I needed to buy it and do the same. I was delighted to find an essay titled “Good-by to James Agee.” James Agee had already become one of my local heroes, but I still find it a lovely happenstance that a book once owned by East Tennessee’s greatest poet led me to a classic essay about East Tennessee’s greatest prose writer.

My first face-to-face meeting with Jeff Daniel Marion came a couple of years later, while I was still an undergraduate. Danny and his wife, poet Linda Parsons Marion, gave my poem “White Scars,” first-place honors in the 1997 Libba Moore Gray Poetry Prize, given by the Knoxville Writers’ Guild. I was invited to read my poem at a reception in the beautiful Laurel Theater in the Fort Sanders area of Knoxville, from the same stage where I had watched enthralled as Galway Kinnell read, recited, and half-sung his amazing poems. My parents and uncle drove in from Sharps Chapel for the reading, and many friends from school came, but the highlight of the evening for me was my first conversation with Danny Marion.

I was surprised by how seriously he took me, a fairly scrappy-looking undergraduate, who had somehow managed to beat out some real writers for a poetry prize. I was struck by how intently he listened to what I had to say and by how many questions he asked me. He seemed impressed that I admired James Wright’s poetry and that I had read Cormac McCarthy and Wilma Dykeman. Danny asked what I planned to do after my time at UT, and I somewhat bashfully said that I was thinking about applying to graduate schools, maybe even to pursue poetry writing. He smiled. “Have you thought about Cornell?” he asked. I think I laughed out loud, and said, “That’s kind of a long shot, don’t you think?” Then Danny said exactly what I needed to hear at that time: “Well, I don’t know about that. You’ve got the talent to try for a long shot or two.” After only that first meeting, he offered to write an informal letter on my behalf to his friend Robert Morgan, a professor at Cornell, and that undoubtedly helped open a door for me that I never would have imagined otherwise.

I was surprised by how seriously he took me, a fairly scrappy-looking undergraduate, who had somehow managed to beat out some real writers for a poetry prize. I was struck by how intently he listened to what I had to say and by how many questions he asked me. He seemed impressed that I admired James Wright’s poetry and that I had read Cormac McCarthy and Wilma Dykeman. Danny asked what I planned to do after my time at UT, and I somewhat bashfully said that I was thinking about applying to graduate schools, maybe even to pursue poetry writing. He smiled. “Have you thought about Cornell?” he asked. I think I laughed out loud, and said, “That’s kind of a long shot, don’t you think?” Then Danny said exactly what I needed to hear at that time: “Well, I don’t know about that. You’ve got the talent to try for a long shot or two.” After only that first meeting, he offered to write an informal letter on my behalf to his friend Robert Morgan, a professor at Cornell, and that undoubtedly helped open a door for me that I never would have imagined otherwise.

As I approach my fortieth birthday, I can look back over my life so far and pick a handful of days that really set the course for what my future would become. That evening in the Laurel Theater when I met Danny Marion is one of those days, and not just because it led me to Cornell, where I would study with Robert Morgan and A.R. Ammons and linger in the presence of great minds like M.H. Abrams, Dan McCall, and so many others. That evening opened an ongoing conversation with Danny Marion that has lapsed on only a few occasions since and hardly ever for more than a week or two at a time in the decade since I moved back to East Tennessee. From the beginning, this conversation involved poets we admired, movies that excited us, restaurants we would have to be out of our minds to miss, writers who should be better known, eccentric family members, and, always, new poems we were writing.

Marion’s poetry takes its place as one of the true jewels of Tennessee literature, on the high shelf alongside the works of James Agee, Cormac McCarthy, Peter Taylor, and Randall Jarrell. Though he was never my classroom teacher, I have learned as much from Danny Marion as from anyone about how to write an authentic, truthful, searching poem. I have learned from his example and from his line-by-line consideration of my poems. Many of the poems in my first book, Tennessee Landscape with Blighted Pine, are stronger because of his suggestions. Perhaps even the title of the book would have been different without his assurance that an unorthodox title could still be the book’s true name. I needed that confidence to let the book embrace the place that inspired so much of it.

Marion’s poetry takes its place as one of the true jewels of Tennessee literature, on the high shelf alongside the works of James Agee, Cormac McCarthy, Peter Taylor, and Randall Jarrell. Though he was never my classroom teacher, I have learned as much from Danny Marion as from anyone about how to write an authentic, truthful, searching poem. I have learned from his example and from his line-by-line consideration of my poems. Many of the poems in my first book, Tennessee Landscape with Blighted Pine, are stronger because of his suggestions. Perhaps even the title of the book would have been different without his assurance that an unorthodox title could still be the book’s true name. I needed that confidence to let the book embrace the place that inspired so much of it.

One of the most persistent themes in the poetry of Jeff Daniel Marion is a recognition of transience, that what is here now can quickly vanish into the air, and that, as John Keats writes in his “Ode to a Nightingale,” “Fled music is sweeter….” Water is a constant image in Marion’s work, particularly his beloved Holston River, among the handful of muses for his poetry. Water and time, always moving, despite the occasional appearance of stillness or tranquility. I have learned through Marion’s poems that there is not only uncertainty but also beauty in that state of motion.

Many poems by Appalachian writers depict speakers searching for the lost past, a history they know about from elders and from community stories, but one that seems just on the cusp of fading away forever. Jeff Daniel Marion’s work presents many examples of this search, most clearly in his poem “Ebbing & Flowing Spring.” The poem opens with Marion’s speaker returning to a familiar location, a springhouse, but finding it changed: the gourd used for dipping water has disappeared. Feeling the absence of the gourd, and the people who drank from it, the speaker traces a path back through time by recalling the stories told to him by an elderly woman named Matilda. Her stories cannot recreate the living past, but they can preserve its memory. The poem ends with the speaker accepting the pain of the icy water held in his cupped hands, “the cold/ that aches and lingers,” in exchange for the solace of drinking the fresh water, just as the pain of loss is exchanged for the consolation of memory.

Marion’s poetry has been considered mostly in the context of Appalachian literature, and few writers have done more to establish and promote a sense of regional identity in their work. However, this identification risks offering a limited view of Marion’s writing, which in fact engages with several national and global literary traditions. One of his most striking poetry collections is titled The Chinese Poet Awakens, in which the poems are spoken in the voice of a Chinese poet, probably an ancient observer, who is set down amongst the days and ways of East Tennessee. These are poems in the manner of Li Po, Han Shan, and Wang Wei, yet they “awaken” to the possibilities of life in the most unlikely of places. I had an alternate paper in mind for this festival, and it is a paper I still feel needs to be written, titled perhaps, “Hosannas Forever: Jeff Daniel Marion and the American Transcendental Impulse.” Marion’s work is overdue to be considered as an accomplished representative of the central grain of American literary tradition, the grain that begins in Ralph Waldo Emerson and descends through Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, out of the Flowering of the New England Mind, the American Renaissance, and into our contemporary literature.

Marion’s poetry has been considered mostly in the context of Appalachian literature, and few writers have done more to establish and promote a sense of regional identity in their work. However, this identification risks offering a limited view of Marion’s writing, which in fact engages with several national and global literary traditions. One of his most striking poetry collections is titled The Chinese Poet Awakens, in which the poems are spoken in the voice of a Chinese poet, probably an ancient observer, who is set down amongst the days and ways of East Tennessee. These are poems in the manner of Li Po, Han Shan, and Wang Wei, yet they “awaken” to the possibilities of life in the most unlikely of places. I had an alternate paper in mind for this festival, and it is a paper I still feel needs to be written, titled perhaps, “Hosannas Forever: Jeff Daniel Marion and the American Transcendental Impulse.” Marion’s work is overdue to be considered as an accomplished representative of the central grain of American literary tradition, the grain that begins in Ralph Waldo Emerson and descends through Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, out of the Flowering of the New England Mind, the American Renaissance, and into our contemporary literature.

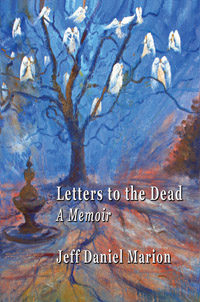

Jeff Daniel Marion has just released his ninth collection of poems, Letters to the Dead: A Memoir, a book that illuminates the importance of what one learns from those who have passed before us and also how much one might still have to say to them. These poems are as much Ode as Elegy, and it is a testament to Marion’s gifts that they are infused with as much joy as sadness.

Marion’s accomplishments are as impressive as they are various. He has performed distinguished work as an editor, letterpress publisher, and photographer. He has been awarded and recognized by countless organizations, including the 2011 James Still Award for Writing about the Appalachian South by the Fellowship of Southern Writers. To his friends, he is just as well regarded as a world-class fountain-pen connoisseur, for his logbook of poems handwritten by their authors, for his expert palate for fine Indian cuisine, and for the shrine he has made to all things fine and literary at his Holston River house.

Through the years, my friendship with Danny Marion has grown beyond exchanging poems and trading opinions about overlooked writers, though we still do those things on a regular basis. We have grown into friends who talk about what it means to be a son, a husband, and a father, what it means to be a recorder of stories and lives, especially those that might not get told or seen or understood if we ourselves fail to get them right in our telling. We talk about how to love places even after they have changed from what we originally loved, how to call places home even when their politics drive us half-crazy and make us want to pull out the dwindling amounts of hair we have left between us. It seems that so many of our talks have become about how to love. And what home means. How to be part of a place and how to show it to the rest of the world, if the world cares to look. These conversations themselves have become acts of love, and they sustain me in every responsibility I maintain. The lesson Danny Marion’s friendship has offered me is that no single role defines us, that we truly are large, multitudinous, and that the fullest life is the one taken in with the widest embrace.

[This essay appeared originally on April 11, 2013.]

Jesse Graves is the author of Tennessee Landscape with Blighted Pine, which won both the Weatherford Award and the Appalachian Writers’ Association Book of the Year Award in Poetry. He teaches at East Tennessee State University in Johnson City.

Jesse Graves and Jeff Daniel Marion will appear at the twenty-fifth annual Southern Festival of Books, held in Nashville October 11-13. All festival events are free and open to the public. To read an interview with Marion, click here. To read a poem by Marion, click here.