Inventing Tennessee's own Yoknapatawpha County

Novelist William Gay talks with Chapter 16 about his books, his beginnings, and why he writes better in Hohenwald than anywhere else on earth

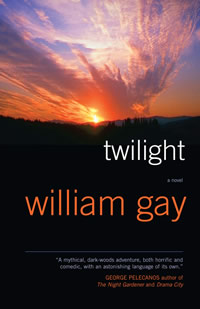

In just over a decade, William Gay has gone from being an unpublished drywall hanger to one of Tennessee’s most acclaimed living writers. Often compared to William Faulkner, Erskine Caldwell, and Thomas Wolfe, Gay was born in 1943 in Hohenwald, Tennessee. After living in New York and Chicago in the 1960s and ’70s, he returned to his hometown—where he still lives—to work in construction by day and write fiction by night. His first novel, The Long Home, won the 1999 James A. Michener Memorial Prize. He subsequently published two novels, Provinces of Night and Twilight, and a book of short stories, I Hate to See that Evening Sun Go Down. In 2007 Gay was named a USA Ford Foundation Fellow, and in 2010 he will publish his fourth novel, The Lost Country.

Chapter 16: Edgewater, the protagonist in your new novel The Lost Country, is a guy getting out of the Navy and traveling around a bit—an experience you yourself had as a young man. How much of the character is autobiographical, and are there other autobiographical elements in the book?

Gay: There probably are. I’m probably closer to Edgewater than any of the other characters I’ve written about. Edgewater is like an alternate me. Philosophically we’re similar; he looks at things the way I used to when I was younger. When I got out of the Navy, I’d already been writing, and it was my idea to bum around, have what adventures I could, and then write about them at my leisure.

And I thought in order to be a writer you had to leave where you are from and see other places. I thought all novelists had to go to New York City, so I was in New York for a while, but not much was happening. Then I lived in Chicago; I worked there in a pinball machine factory for a while. I eventually came back here, met a girl. We got married, started having kids, and I had to find a way of making living. I wound up being a carpenter, a drywall hanger, and different aspects of construction work. All the time I was writing on the side, writing at night, typing things up, trying to get an agent. It was only when I started writing about things I was familiar with that anything clicked, that it started to feel right. I had been trying to write about expatriated artists living in Paris or something—exotic things I didn’t know about except what I had read. When started writing about the sort of people I grew up with, hung around the pool room with, drank with, it just rang truer. I could tell it was better right away.

And I thought in order to be a writer you had to leave where you are from and see other places. I thought all novelists had to go to New York City, so I was in New York for a while, but not much was happening. Then I lived in Chicago; I worked there in a pinball machine factory for a while. I eventually came back here, met a girl. We got married, started having kids, and I had to find a way of making living. I wound up being a carpenter, a drywall hanger, and different aspects of construction work. All the time I was writing on the side, writing at night, typing things up, trying to get an agent. It was only when I started writing about things I was familiar with that anything clicked, that it started to feel right. I had been trying to write about expatriated artists living in Paris or something—exotic things I didn’t know about except what I had read. When started writing about the sort of people I grew up with, hung around the pool room with, drank with, it just rang truer. I could tell it was better right away.

Chapter 16: What was that like, going from working construction to being a famous novelist?

Gay: It was real jarring, to be honest about it. I got divorced about the same time I first started to get published. There was probably no connection between the two things, but I sort of made one. I was being given something on the one hand, and something was being taken away on the other. It was like fate balancing things out. I was perfectly content being married; I didn’t want to get divorced. But the writing had been a problem all along, as far as my marriage went. It was not something my wife thought was a good idea. She thought it was ridiculous for a guy from Tennessee to try to write novels. About the time she split, I sold a couple of stories to literary magazines, and then I met up with Greg Michaelson from The Missouri Review, who was also an acquisitions editor for McMurray and Beck, [a press] which later became MacAdam/Cage.

… the writing had been a problem all along, as far as my marriage went. It was not something my wife thought was a good idea. She thought it was ridiculous for a guy from Tennessee to try to write novels.

I’m still a little surprised by it, frankly. I was a member of Cormac McCarthy’s cult audience back when Cormac was not cool, when no one read him hardly. I thought it would be great to have a cult audience. Not a lot of people, but enough to buy the book so that it would encourage the guy who published it to publish the next book. That’s what I expected. I expected a few decent reviews, but there were actually more than I expected. And they were frankly better than I had expected.

Chapter 16: Even in The New York Times Book Review.

Gay: Yeah, Tony Earley wrote that. I think probably going to [the] Sewanee [Writers’ Conference] for the first time helped me more than anything else. I’d never been around writers, never actually met a person who made living writing. It was a totally different environment up there. I met all these people, made friends who are still really close, like Tommy Franklin. I talk to him every few days, and we’re still really good friends, along with his wife Beth Ann [Fennelly]. The first person I met up there was [author] Barry Hannah. Barry has been kind to me; he wrote a couple of good blurbs. Always helped me where he could.

Chapter 16: What’s it like to be a famous writer in rural Tennessee, and not some literary hotspot like New York?

Gay: I lived in Oxford [Mississippi] for a while. I was going with a woman, and we lived on South Lamar, close to Rowan Oak, Faulkner’s house. I liked living in Oxford, but my kids all lived here—I have four kids who are all grown—and I felt I couldn’t work as well other places as I can here. I don’t know what it is about that. I’m close to the place I grew up, and the countryside, the natural part of it, hasn’t changed. The town has, but I don’t go to town that much anyway.

I try not to think about what it’s like being a writer and living here. I tried not to ever have that mentioned. It sounds ridiculous, but that’s what I thought—that if I don’t talk about it, no one will know. I thought everything would continue like it was, that I could go to the convenience store to buy a six pack and a pack of cigarettes and not get into a literary discussion about who the characters were in some book and if they were based on real people. But it’s hard to stay under the radar, you know.

Chapter 16: Do people recognize you now around town?

I felt I couldn’t work as well other places as I can here. I don’t know what it is about that. I’m close to the place I grew up, and the countryside, the natural part of it, hasn’t changed. The town has, but I don’t go to town that much anyway.

Gay: Basically the only places I go are the library and the grocery store, and the librarian knows me and I usually don’t see that many people in the grocery store. I was sort of a loner to begin with, and that hasn’t changed much. I was preoccupied with my family. I didn’t have a lot of friends; I didn’t go out socially. It’s just a full time job making a living, especially if you do hard physical stuff like hanging drywall. Right [when] I began to get published, this woman asked if I had someone who helped me with my writing. I said, “What do you mean by that?” And she said, “Well, I knew your family a long time, and they’re not that smart. I knew you when you were younger, and you’re not that smart. I was wondering if you had somebody who took out the little words and put in the big words.”

Chapter 16: What did you say to that?

Gay: There was nothing to say. I just turned my head and walked away.

Chapter 16: Most of your novels and stories revolve around a fictional town in rural Tennessee called Ackerman’s Field, sort of like Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County. Was that a conscious decision, or did it just emerge that way?

Gay: It was more of conscious decision. I was real familiar with Yoknapatawpha County and Jefferson and all that kind of stuff in Faulkner’s work. When I was a kid we lived in a place called Grinder’s Creek. We didn’t have a car—I grew up pretty poor—so on Sunday we used to walk to my grandmother’s house. And we went through the woods to get there, and we always went through this big field where there used to be a house. I asked my father what was the name of that field, and he said it was Ackerman’s Field. And I asked him why it was called Ackerman’s Field, and he didn’t know; he said it was just because someone named Ackerman once owned it. That stayed with me, and when I needed a town in my first published novel, I made my town Ackerman’s Field.

And a lot of the stuff in my stories takes place in this really wild place called the Harrikin. I used to hunt ginseng there, although it’s not like it is in my writing. It was a huge area of land that was owned by absentee companies. No one could buy or sell land there; nobody built there. At one time there were iron ore mines and a smelter there, but they had been abandoned when the iron ore ran out, and the people left, too, because they didn’t own the land; they were living on company land. It was just abandoned. I accidentally discovered it years ago, looking for a place I could prowl around in the woods and not walk up into somebody’s backyard. I fell in love with the place. It was wild; no one had been traveling there for I don’t know how many years, probably since the early part of the twentieth century. It was a big area that covered part of the southern part of Lewis County, and touched on Lawrence and Wayne counties. I would find places where those old houses used to be. And it was like you could pick up vibrations or something from the lives that had been lived there. All the hard times they had, the ups and downs. Like it was still alive.

And a lot of the stuff in my stories takes place in this really wild place called the Harrikin. I used to hunt ginseng there, although it’s not like it is in my writing. It was a huge area of land that was owned by absentee companies. No one could buy or sell land there; nobody built there. At one time there were iron ore mines and a smelter there, but they had been abandoned when the iron ore ran out, and the people left, too, because they didn’t own the land; they were living on company land. It was just abandoned. I accidentally discovered it years ago, looking for a place I could prowl around in the woods and not walk up into somebody’s backyard. I fell in love with the place. It was wild; no one had been traveling there for I don’t know how many years, probably since the early part of the twentieth century. It was a big area that covered part of the southern part of Lewis County, and touched on Lawrence and Wayne counties. I would find places where those old houses used to be. And it was like you could pick up vibrations or something from the lives that had been lived there. All the hard times they had, the ups and downs. Like it was still alive.

Chapter 16: In your novel Twilight, you explain that the name “Harrikin” comes from a hurricane that passed through there. Did that really happen?

Gay: That’s actually true. It’s not really called the Harrikin, but a hurricane did touch down there in the 1930s and left a tangle of trees and the sort of stuff I described. And there are also these holes; they’re like wells. You gotta kind of watch where you’re going. I used to hunt ginseng in the fall after the berries got on it, and up to Christmas, to help augment the Christmas money. Ginseng was going up at the time. It was two hundred, three hundred dollars a pound. If you could find a pound of ginseng, that was a good way to work.

Chapter 16: There’s not much around anymore?

Gay: I planted the seeds from the berries, so there’s probably some down there. There’s probably ginseng around there in the Harrikin, but not so much elsewhere. Much of it got dug up. It got up to six hundred, seven hundred dollars a pound around the period when I stopped digging, and at that point everyone in the woods was looking for ginseng and would dig up even itty bitty plants. That would kill a lot of it.

Chapter 16: In your new book, you have some of the action take place outside Ackerman’s Field. That’s sort of a departure for you.

I was a slow study; it was hard for me to learn a lot of things because I was kind of stubborn. And when editors would take the time to respond personally to my stuff, they said, “You need to stop using metaphors and similes and get on with the story. You’re describing storms and weather, and this quasi-poetic stuff is slowing things down.” But I love language.

Gay: I do start it in different places, but by partway through Book Two it’s back in Ackerman’s Field. Edgewater has met the person he’s going to marry—disastrously, by the way. Edgewater is a dead serious guy, but Rooster Fish, the other chief protagonist, is sort of … a lot of funny stuff happens to him. He’s not quite comic relief. I like to write comic things, even though it’s usually pretty dark.

Chapter 16: There’s certainly not a lot of humor in your earlier work. How do you think your own writing has changed?

Gay: I was a slow study; it was hard for me to learn a lot of things because I was kind of stubborn. And when editors would take the time to respond personally to my stuff, they said, “You need to stop using metaphors and similes and get on with the story. You’re describing storms and weather, and this quasi-poetic stuff is slowing things down.” But I love language. The thing I loved about McCarthy and Thomas Wolfe and Faulkner is their language, and if I had to crank out a story like True Confessions or something where I didn’t get to use what they call quasi-poetic language, that wouldn’t be any fun. That’s the fun of it, thinking of new phrases and new twists on old phrases. I still do that. How it’s changed—I think it’s tightened up a lot. I saw that I was overwriting a lot. I tried not to do too much of it but still keep the mythic quality that I wanted. I was listened to a lot of folk music when I was writing the book, I was listening to Harry Smithson, and I wanted the same quality in my writing as I heard in this old music—almost like a folk tale, a legend.

Chapter 16: You’ve been publishing for about a decade now, and in that time the popularity of Southern writers has exploded. Why?

Gay: I do have a theory about that. You’re exactly right when you say that there’s more interest than when I started publishing. For years, I kept up with that stuff, I read Writer’s Market, Writer’s Digest, that sort of stuff, and there seemed to be this East Coast thing going on in fiction. Most of the novelists who were well known were from New England or New York—Mailer and Philip Roth and people like that. I guess Barry Hannah was the only prominent Southern writer at the time, and he wasn’t as prominent as Mailer or Roth or those guys. And he had this guy at Esquire helping Barry, pushing his stuff. I think what happened, and this is just my idea, is that Cold Mountain came along and it was so successful, and in 1992 Cormac McCarthy won the National Book Award with All the Pretty Horses, and I think that editors started paying more attention to Southern writers. I know when I signed on with my agent, she said she had been looking for Southern writers. She said she had got caught in the rain one day, she went into in a Barnes & Noble in New York City and started to read one of my stories in The Georgia Review. And by the time she was done, she was already making plans to call me.

[Literary success] is like a crap shoot. Like rolling the dice. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. I don’t really understand it. But I’m a little superstitious about it. If I start looking for an explanation, it’ll all go away. What I wanted to be most in life was a writer, and it sometimes seems unreal that that’s what I am. I’m not saying I’m famous, but I have published stuff, and readers know who I am. I never considered myself a writer before I actually got paid for it. The way I looked at it, if someone eventually paid you, even fifteen cents, if they saw any monetary value, you were a writer. As long as you were sending stuff out, getting it back, that was it was like trying to be a writer.

I did a lot of the wrong things. When I finished a story I would send it to The New Yorker; when it came back I’d send it to Esquire, then Harper’s or The Atlantic or somewhere. When I learned about literary magazines, I got some sample copies, and when I started submitting to them, I started getting accepted. Not sure why that is. I was interested in making living at it. I knew The New Yorker was a top market, that it paid good rates. Literary magazines sometimes pay in contributor copies because they do not have any money. But I was really surprised by the quality of stuff in them. Told one editor that, that I was surprised, and he said if only there were as many good fiction readers as writers he would be in a little better position.

Chapter 16: Did you have anyone around reading and helping you when you were getting started?

Gay: I was pretty isolated. I was like a gay guy in the closet. If you’re working construction and you go out on Monday where the guys are talking about the football game or skinning a deer, you don’t pull out the sonnet you wrote over the weekend and read it to them. It was compartmentalized. Everyone was surprised when I began to publish stuff. No one was really interested, frankly. Most people close enough to me to know about it, I think they considered it a harmless aberration, like a hobby, something I did for own entertainment.

What I wanted to be most in life was a writer, and it sometimes seems unreal that that’s what I am.

That was never my design. In seventh grade, I first read Thomas Wolfe and that determined what I would be, whether successful or not. I had teacher who noticed I was reading a lot of books, but he didn’t think the books I was reading were very good. And so he asked me one day if he gave me a book would I read it, and I said yes. And he said if you read it you can have it, and he gave me Look Homeward, Angel. I was mesmerized by Wolfe. Then he gave me The Sound and the Fury, As I Lay Dying.

Chapter 16: And there was no turning back at that point?

Gay: I wasted a lot of time trying to write like Thomas Wolfe. I guess I’m not the only one; a whole lot of people in my generation were trying to write like Thomas Wolfe. A new edition of Look Homeward, Angel came out last year, and the publishers asked several people they knew had been swept away by Wolfe when they were young to write about their initial experience with Wolfe. I did that, Pat Conroy did that, Charles Frazier, several southern writers who were influenced by Wolfe, and they published our pieces in the introduction. I thought that was kind of neat. Like blurbing Thomas Wolfe.

READ an excerpt from William Gay’s work in progress, The Lost Country.