Round Two

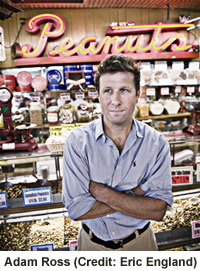

On the cusp of publishing his second book in a year, Adam Ross talks with Chapter 16 about women, men, and life since Mr. Peanut

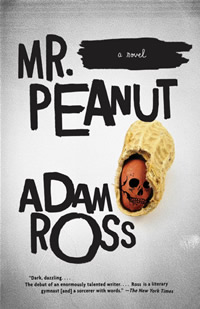

In March 2010, Adam Ross was a former bartender/editor/teacher whose first novel, fifteen years in the writing, had just been shipped to advance reviewers. Early praise from Publisher’s Weekly (“an inspired debut … that readers into the darker end of the literary spectrum won’t want to miss”), Kirkus (“an intellectual noir novel that shows evidence of an original voice”), and the like helped propel Mr. Peanut to an initial print run of 60,000 copies—virtually unheard of for a debut novel—and to sales of foreign rights in fourteen countries. But the most stunning early report came from none other than Stephen King himself, who called the book “the most riveting look at the dark side of marriage since Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?“

When Mr. Peanut hit stores last June, the praise continued, here and abroad, inspiring assessments like “ingenious,” “brilliant,” “riveting,” “audacious,” “arresting,” “forceful,” “involving,” “stirring,” “original,” “harrowing,” “bleakly convincing,” “unflinching,” and “mesmerizing.” But if critics were nearly unanimous in offering paeans to the brilliance of Ross’s writing, they weren’t always in agreement about the success of Mr. Peanut as a constructed work of fiction. After noting “the rich and variegated gifts of this audacious new writer”, New York Times critic Michiko Kakutani ultimately pronounced Mr. Peanut “a heap of mirror fragments lying jumbled together.” Three days later, however, in the very same newspaper, Scott Turow gave a passionate defense of the novel . In a front-page rave, he declared it “an enormous success—forceful and involving, often deeply stirring and always impressively original. This is a brilliant, powerful, memorable book.”

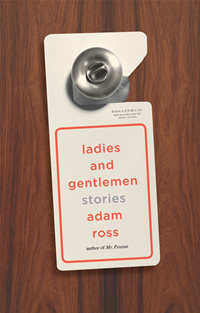

A year later, Ross is back with Ladies and Gentlemen, a new collection of short stories. Due on shelves June 28, it considers many of the same questions raised in Mr. Peanut: the human temptation to cruelty, the simultaneously redemptive and damning nature of passion, the difficulty in forging an integrated and identifiable self from disparate and sometimes self-contradictory impulses and desires. Unlike Mr. Peanut, however, the stories unfold within a very traditional structure, and critics have been anticipating this book since they first heard of Adam Ross. As Christopher Taylor wrote of Mr. Peanut last year in The Guardian: “Ross’s range is the main thing it highlights: he’s equally at home riffing wittily on Manhattan sauna etiquette, inhabiting the consciousness of a neglected 50s trophy wife, adding a touch of humour to snappy noir pastiche, and describing an illicit affair with controlled eroticism. The story collection he’s working on should really be something.”

A year later, Ross is back with Ladies and Gentlemen, a new collection of short stories. Due on shelves June 28, it considers many of the same questions raised in Mr. Peanut: the human temptation to cruelty, the simultaneously redemptive and damning nature of passion, the difficulty in forging an integrated and identifiable self from disparate and sometimes self-contradictory impulses and desires. Unlike Mr. Peanut, however, the stories unfold within a very traditional structure, and critics have been anticipating this book since they first heard of Adam Ross. As Christopher Taylor wrote of Mr. Peanut last year in The Guardian: “Ross’s range is the main thing it highlights: he’s equally at home riffing wittily on Manhattan sauna etiquette, inhabiting the consciousness of a neglected 50s trophy wife, adding a touch of humour to snappy noir pastiche, and describing an illicit affair with controlled eroticism. The story collection he’s working on should really be something.”

Prior to the publication of Ladies and Gentlemen, Ross offered Chapter 16 readers a sneak peak at the novel and answered questions about the book via email:

Chapter 16: Mr. Peanut inspired a remarkable range of opinions, the two-sided approach by The New York Times being only the most obvious example. Were you at all unnerved by the inconsistency? You were a debut novelist—one, moreover, who had spent well over a decade working alone, with no editor or agent urging you on—and it’s hard to imagine there was any way you could have been prepared for either the attention the book received or the extremely passionate ways, both good and bad, that reviewers responded to it.

Ross: Nothing prepares you for the attention, and I think if I were a younger writer, I’d be a basket case. Within the last several weeks, for instance, I came upon one British blogger’s review that was nearly a screed, followed by Australian writer Alice Grundy’s rave in Crikey, followed by another review by a librarian praising the book to the roof beams, followed by a mom in the Oak Hill camp carpool who told me she was so unnerved reading it in bed next to her husband that she took it with her to the bathroom, followed by yet another by Daniel Roberts (a writer for Fortune magazine) that comprehensively addressed several common misconceptions about the book and then subsequently and thoughtfully knocked them all down.

The experience could be vertiginous but I look at it as a good thing. The various opinions suggest that the book has an impact, that it gets a reaction—which isn’t what I set out to do, mind. But no, it’s not unnerving, because I recognized early on that the book no longer belonged to me and would have to defend itself. My hope, always, is that it’s read on its own terms.

Chapter 16: In “Middleman,” an older man tells a boy, “Getting inside is everything. … When you’re outside, you might not think you’re good enough. Don’t believe it. Just get in there first. Then you’ll figure it out.” You’re on the verge of publishing your second book in twelve months. Does it feel like you’re in there yet?

Ross: I just received hardback copies of Ladies and Gentlemen and I’m here to tell you that I’m no jaded insider. I was so excited simply holding the book I didn’t know what to do with myself.

Chapter 16: I hope you won’t take this the wrong way, but you’ve assembled quite a collection here of men (and boys) who contend with one kind of metaphorical impotence or another. There’s no actual Jake Barnes among them, but still: is this a commentary of any kind on the state of being male in the twenty-first century?

Ross: Go on, I can take it. Describe to me their metaphorical impotence.

Ross: Go on, I can take it. Describe to me their metaphorical impotence.

Chapter 16: Almost all of them are profoundly, urgently moved by fundamental desires that drive their behavior but that they are powerless to realize. Many are men who are simply ill-fitted for the world in which they find themselves. They can’t will themselves to stop wanting, and they can’t will themselves into fulfilling their own desires.

Ross: You know, just the other day, my wife and I were taking a bath outside. We have a pair of tubs we’ve installed next to each other in the yard so we can hold hands while we stare at the birds in the trees. The moment was right, I was ready, and then she whispered, “Do you ever wonder if your characters are deluding themselves into thinking they have abilities they actually lack?” Total soft-off.

I do agree with your observation. Being “ill-fitted” for the world drives conflict in these stories because the characters are presented with opportunities to make a place for themselves morally, spiritually, or emotionally. Some fail. Some succeed heroically.

Chapter 16: I hope you won’t take this the wrong way, either, but here’s a related observation: many of these stories strike me as aggressively male and aggressively heterosexual.

Ross: What do you mean by that?

Chapter 16: Oh, come on. Practically every male character in the book, on encountering a woman, immediately fantasizes about what it would be like to have sex with her—on the desk, in the hallway, in the dorm room, on the park bench.

Ross: You have beautiful eyes, by the way.

Chapter 16: Oh, wow, really? You think so? Honestly, though, the point of view in most of the stories strikes me as either overtly or subtly that of a guy on the hunt.

Ross: I cannot say for certain, then, that this is my book. I can say that men think way too much with their Weiners.

Chapter 16: I’m interested in the fact that you’ve given the full collection the same title as the one story that’s written from a female point of view—in fact, from an incredibly empathetic understanding of the female point of view. Any comment?

Ross: My wife wrote it. Seriously, that’s one of my favorite stories in the collection because I wanted to write about how working mothers are tugged in a hundred different directions. Sara, the main character, is conjoined with Marnie in “Futures,” Ashley in “The Rest of It,” and Maria and Carla in “In the Basement,” because all of them struggle with their allegiances to children and husbands who may be flailing. Unlike the men, it seems to me, they have a greater inborn sense of loyalty.

Chapter 16: When a writer publishes a second book, it’s customary for reviewers to look for a kind of evolution that might have taken place since the first book appeared, but you’d already written almost all the stories in Ladies and Gentlemen before you finished Mr. Peanut. Is it fair to say that this book is more of a companion volume—a structurally more conservative exploration of some to the same themes and questions that haunt the novel—than either a predecessor or a descendant of Mr. Peanut?

Ross: It’s a companion to Mr. Peanut, thank you for that, and completely leapfrogs the “sophomore effort” jinx. But it’s also true. When I began Mr. Peanut, I thought I was writing a novella and during fallow periods, wrote stories, which led to visions of a book like Jane Smiley’s The Age of Grief or Philip Roth’s Goodbye, Columbus—a short novel and five stories. In fact, when I sent the work to Mark Kessler, my agent, one of the first things he said to me was, “You have two books here.”

Ross: It’s a companion to Mr. Peanut, thank you for that, and completely leapfrogs the “sophomore effort” jinx. But it’s also true. When I began Mr. Peanut, I thought I was writing a novella and during fallow periods, wrote stories, which led to visions of a book like Jane Smiley’s The Age of Grief or Philip Roth’s Goodbye, Columbus—a short novel and five stories. In fact, when I sent the work to Mark Kessler, my agent, one of the first things he said to me was, “You have two books here.”

Ladies and Gentlemen are stories in a classic mode. They share numerous themes with Mr. Peanut—the struggle for self-awareness, how evil comes in small things, the saving and stultifying cyclicality of relationships—but its focus, as per the George Eliot epigraph, is how the opportunity to commit cruelty can be revelatory of a person’s true character.

Chapter 16: To me the book seems more obviously an exploration of the way people struggle mightily, against enormous odds and sometimes doomed by ridiculous notions, to make some kind of connection with another human being. Not true?

Ross: Completely true. In “Futures,” David Applelow, the desperate, unemployed job-seeker, is trying to do a good turn for his neighbor and her kid, but he’s a loner and this sort of generosity doesn’t come naturally to him. The professor in “The Rest of It” has been shaken to his core by his divorce, is unmoored by his marriage’s destruction and dying to return to life. The narrator of “In the Basement” is struggling mightily to stay connected to his wife and will throw a friend under the bus to preserve his marriage. The brothers in “When in Rome” have suffered cycles of disenchantment and are trying to re-bond with each other. In all cases, however, there is the gap between these characters’ intentions and their self-knowledge which each slips through or manages to bridge.

Chapter 16: These stories follow no template: some are long; some are short; some concern children; some concern adolescents; some concern adults; some feature sympathetic protagonists, and some feature more problematic characters; and so on. For the sake of our readers who are also aspiring writers, I’ll ask one question about process: do you know when you set out where a story is going? Are you sure, for example, that it will always be a short story, that it won’t ever balloon into a novel?

Ross: That wasn’t the case with Mr. Peanut, but generally speaking, yes, and the process is the same: I begin with what I consider a strong, inspired opening that’s conjoined with clear sense of the end. I furrow my way through the middle, often struggling, and that’s usually when the narrative takes a surprising turn, where I’m freest to invent. Once I’ve drafted something, the real challenge is length—what details should be included and which are redundant, are merely exposition. I made a huge, eleventh hour cut to “When in Rome,” nearly six pages, after a discussion with a terrific reader. Didn’t make the production team at Knopf happy but it was a better story for that elision.

Chapter 16: The last time we talked, you were trying to decide between two very different ideas for your next novel. Any decisions yet about what you’ll work on next?

Ross: I have. Its working title is The Tiger’s Wife’s Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Freedom. It’s a love story about wizards set in a war-torn Eastern European city beset by vampires and zombies. It takes place in the near-future. The main character won’t go the f*%k to sleep but when he does invariably dreams of heaven. That’s all I’ll say about it.

[Click here to read an excerpt from Adam Ross’s forthcoming story collection, Ladies and Gentlemen.]