Screwball Bestiary

David Sedaris talks with Chapter 16 about undecided voters, Loretta Lynn, life on book tour, and his new collection of unconventional animal fables

In 1992, David Sedaris was a struggling writer who made ends meet by cleaning houses and doing odd jobs. That was before National Public Radio’s Ira Glass heard Sedaris reading from his diary at a Chicago nightclub and invited him to read on the radio, an invitation that immediately led to an appearance on NPR’s Morning Edition. Sedaris’s highly irreverent essay, “The Santaland Diaries”, which describes his stint as Crumpet the Elf in Macy’s department store, has since become a treasured holiday tradition of the NPR crowd. “Twenty-two thousand people came to see Santa today, and not all of them were well behaved,” Sedaris notes in his mordant takedown of forced holiday merriment. When a customer threatens to have Crumpet fired for being insufficiently helpful, Sedaris is unfazed: “Go ahead. Be my guest. I’m wearing a green velvet costume. It doesn’t get any worse than this.”

“The Santaland Diaries” catapulted him, essentially overnight, into fame and fortune—or at least a two-book deal with Little, Brown. Sedaris has become a staple of Ira Glass’s radio show, This American Life, has won the James Thurber Prize for American Humor, and was named Humorist of the Year by Time magazine. He has written eight books, all bestsellers with a combined seven million copies in print, and several plays. Through it all, the tone set by Crumpet the Elf obtains: Sedaris’s trademark brand of humor is marked by equal doses of caustic, frequently foul-mouthed wit and the sweet wistfulness of the true romantic. Sedaris never misses a chance to point out the absolute idiocy of human beings—including, invariably hilariously, his own mistakes and misadventures—but it’s impossible to read his essays and stories without concluding that he secretly enjoys the parade of human foolishness he’s treated to every day.

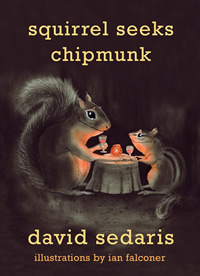

Sedaris is on tour this fall with Squirrel Seeks Chipmunk: A Modest Bestiary, his first foray into fiction. The book, illustrated by Ian Falconer, is a collection of parable-like stories featuring talking animals whose foibles, like those of the creatures in Aesop’s Fables, mimic those of human beings. Naturally, Sedaris’s fables come with a twist. In the title story, a squirrel and a chipmunk fall in love despite their parents’ objections, and then run out of things to talk about on the second date. In “The Toad, the Turtle, and the Duck,” three distrustful strangers standing in line bond over their shared hatred of an oppressive bureaucracy. A mouse adopts a baby snake and is so besotted by motherhood that she fails to notice certain problematic qualities of her child.

Sedaris grew up in Raleigh, North Carolina, but now lives in London with his partner, Hugh Hamrick, an artist. In late October, he spoke with Chapter 16 by phone from his hotel room in California.

Sedaris grew up in Raleigh, North Carolina, but now lives in London with his partner, Hugh Hamrick, an artist. In late October, he spoke with Chapter 16 by phone from his hotel room in California.

(A brief note: the conversation that follows is not rated G. Fans of David Sedaris will find it unsurprising, but readers sensitive to graphic language might prefer to read one of the many, many other interviews, reviews, articles, poems, or essays on offer at Chapter 16.)

Chapter 16: You’re staying in a national hotel under your own name.

Sedaris: I think I always do.

Chapter 16: But you’re kind of a rock star, aren’t you?

Sedaris: No. I mean, sometimes when you stay in a really good hotel you want to talk them up on stage—do a little commercial for the hotel—because that way when you go back, they’ll upgrade your room. Even when I’ve done that, championed the hotel I’m staying at, even then no one’s ever called me.

Chapter 16: I’m amazed. When you’re on lecture tours, you always seem to have huge, huge crowds adoring you.

Sedaris: Yeah, but no one’s ever knocked on my door or anything like that.

Chapter 16: So you’re back in the States in an election year, and I’ve been thinking about that New Yorker essay you wrote in 2008. Do you feel the same way about undecided voters this year?

Sedaris: I was listening to the radio yesterday, and they talked the election to death. They were already in the post-mortem of the election, and then they revived it again. Don’t even get me started on that.

Chapter 16: Oh, please. I would love to get you started on that.

Sedaris: So this guy called in and said, “I’m an undecided voter,” and he said, “My problem is that neither of the candidates are speaking to my needs.” And I just thought, “Oh, shut up. You’re just somebody who wants attention.” How can you not decide between Andrew Cuomo and what’s his name, that maniac who’s running for governor in New York State? How can you be undecided? “Neither of them are speaking to my needs.” Well, neither of the candidates has addressed my fear of snakes. I’m terrified of snakes, and no one has talked about it. They didn’t mention that at all. And I have a real problem with that.

Chapter 16: When you hear comments like that, are you glad to be an expat?

Sedaris: Well, I still vote in the United States. My boyfriend, Hugh, he can tell you everything about the coalition government in England. And he has no idea what the Tea Party is. I can’t make that emotional jump. I am obsessed with the news of the United States, and it would feel really wrong not to be here during the election. I was in Kentucky the other day, and I saw Rand Paul signs.

Sedaris: Well, I still vote in the United States. My boyfriend, Hugh, he can tell you everything about the coalition government in England. And he has no idea what the Tea Party is. I can’t make that emotional jump. I am obsessed with the news of the United States, and it would feel really wrong not to be here during the election. I was in Kentucky the other day, and I saw Rand Paul signs.

Chapter 16: Did you see a Rand Paul supporter stepping on anyone’s head?

Sedaris: And now the person that stepped on the girl’s head wants an apology—I guess for getting under his foot. I don’t know. Step on someone’s hand if you have to, but their head? I saw that video, and you really have to lift your foot to step on someone’s head.

Chapter 16: I didn’t realize you were here for every election season. Do you deliberately time your tours so you can vote?

Sedaris: Normally, I go on a lecture tour every fall and every spring. So every autumn I’m in the United States. This is the first time I’ve ever released a book in the fall. So I started a lecture tour on September 26, and then I have three or four days off [before] I start my book tour.

Chapter 16: You mean you’ve been giving a reading every single night since September 26?

Sedaris: Every single night. Well, there was one night where we had to change the date of a show, and so that gave me one day off. Instead of going from Rochester to Baton Rouge and then Philadelphia, I went from Rochester to Philadelphia and had a Saturday night off. But other than that I’ve had a show every night.

Chapter 16: You frequently have people standing in line for hours to meet you. Is this something that happens even with your lecture tours, or only in bookstore signings?

Sedaris: You sell more books in a bookstore than you do in a theater. I don’t care how big the theater is. Like the Chicago Theater seats 4,000 people, but you sell more books in a store. I don’t know why that is. I think because the stores have really got it organized. They give people numbers, and so people know they can go out, go to dinner and a movie, or raise a family, and then come back. I think my record is signing books for ten and a half hours.

Chapter 16: Where was that?

Sedaris: I don’t remember if it was Louisville or Kansas City. Or it could have been Fargo. It could have been Fargo, or it could have been Lincoln, Nebraska. Those are good places to go on a book tour.

Chapter 16: We just ran an interview with Loretta Lynn last week, and she doesn’t even open the blinds on her bus anymore because the highways all look the same to her now.

Sedaris: Loretta Lynn is my inspiration. When I was fifteen, I worked at the Dorton Arena in Raleigh, and I sold popcorn, peanuts, and ice-cold drinks for whatever was going on. They had rock shows there—like Black Sabbath, Alice Cooper—and I would go up and down the aisles and sell popcorn, peanuts, and ice-cold drinks. They [also] had country jamborees, and at that age I wasn’t willing to admit that I liked country music. But Loretta Lynn would come, and she would sign books, sign ticket stubs and stuff, for hours and hours and hours. And I just remember thinking, “That’s really smart.” And she’s still touring. And other people aren’t. She was really good to the people who came to see her.

Sedaris: Loretta Lynn is my inspiration. When I was fifteen, I worked at the Dorton Arena in Raleigh, and I sold popcorn, peanuts, and ice-cold drinks for whatever was going on. They had rock shows there—like Black Sabbath, Alice Cooper—and I would go up and down the aisles and sell popcorn, peanuts, and ice-cold drinks. They [also] had country jamborees, and at that age I wasn’t willing to admit that I liked country music. But Loretta Lynn would come, and she would sign books, sign ticket stubs and stuff, for hours and hours and hours. And I just remember thinking, “That’s really smart.” And she’s still touring. And other people aren’t. She was really good to the people who came to see her.

Chapter 16: You’ve said you really enjoy meeting the people on tours. You don’t seem to think of book-signing as a burden, even though it sounds very much like a burden.

Sedaris: Well, I have a seat. So it’s not so bad for me. It would be bad if you were standing up. If I had to go to a cocktail party, it would be very hard for me to talk to people. But in a situation like this, I’m in the driver’s seat. I like to have a little theme sometimes for my tours, and this time I’ve been asking people for jokes.

Chapter 16: Did you get any good ones?

Sedaris: Last night I was in Boulder, Colorado, and the audience just wasn’t going to laugh at these jokes. Like, what’s the difference between a Camaro and an erection?

Chapter 16: What?

Sedaris, whispering: I don’t have a Camaro. But the audience, forget it.

Chapter 16: You have that great essay — “Author, Author?” — about being in Costco with your brother-in-law to pick up little trinkets to give away at your bookstore signings. What are you bringing this year?

Sedaris:You know, I was giving out condoms. And then my lecture agent got a letter from this woman, and she said, “I came with my fifteen-year-old daughter to see you in Chicago, and you asked the girl how old she was, and when she told you, you slapped a condom on the table.”

Chapter 16: Did the girl think it was funny?

Sedaris: I don’t remember. I mean, I’ve done that to so many people. Thousands of people.

Chapter 16: But you didn’t get thousands of complaints?

“You sell more books in a bookstore than you do in a theater. I don’t care how big the theater is. … I think because the stores have really got it organized. They give people numbers, and so people know they can go out, go to dinner and a movie, or raise a family, and then come back. I think my record is signing books for ten and a half hours.”

Sedaris: Actually, I did only get like three letters or something, but it was enough. So I thought, “I’m not going to give anything out on this tour.” But then I got these cards from the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, and they’re really beautiful letterpress cards, about the size of a business card. And they say, “Stop Talking.” So you could just hand it to someone if they’re on their cell phone, and it doesn’t say, “Shut Up.” It just says, “Stop Talking.”

Chapter 16: People could, say, pass it down the row to somebody who’s whispering during your lecture.

Sedaris: When I thought about the condom thing, [I realized] maybe that was weird. And I guess I thought because I was homosexual that meant it wasn’t creepy.

Chapter 16: Because you weren’t hitting on a fifteen-year-old girl?

Sedaris: Right. My intention was never to make it weird. And if it was just weird, even just those few times, then that’s not good.

Chapter 16: I want to talk to you about the new book, which is very different from your earlier work. You often try out your essays on tour audiences. Did you try any of these stories out, too?

Sedaris: All of them were read out loud, in front of an audience. And I found I had to read them in the beginning of the evening. Because if I were to read essays, and then read one of the stories, by the time people got used to the fact that I was reading fiction, the story would be over. So I found I had to start the evening with one.

Chapter 16: People didn’t know how to take them?

Sedaris: You can feel it when people have just checked out and are not listening to you anymore. And I never got that feeling. I mean, I got this feeling that people preferred it when I was talking about myself. But I don’t think that they disliked [the new stories].

Chapter 16: Obviously not. It’s been on the bestseller lists ever since it came out.

Sedaris: This is something I feel good about. I feel good that it’s really different. I kind of defy anyone to say, “I like that book last year that came out about talking animals more.” It’s hard to think of anything to compare it to.

Chapter 16: Well, it’s been compared to Aesop’s Fables.

Sedaris: Someone said to me, “I see this as bedtime stories for children who drink.” And I thought, “Huh, that’s good.” And someone said it was Aesop without the moral. But there’s kind of a gimmicky way you could do it. Like the story about the hippopotamus: to have a line at the very end that says, “And the moral is: To each his own.” I didn’t want to be corny that way. Because there’s not really a moral to that story. It’s just sort of about this owl that’s kind of lonely and has made friends. I think of it as kind of a sweet story. And then there are other stories that do have a moral. That unevenness feels good to me. I have no idea what other people think.

Sedaris: Someone said to me, “I see this as bedtime stories for children who drink.” And I thought, “Huh, that’s good.” And someone said it was Aesop without the moral. But there’s kind of a gimmicky way you could do it. Like the story about the hippopotamus: to have a line at the very end that says, “And the moral is: To each his own.” I didn’t want to be corny that way. Because there’s not really a moral to that story. It’s just sort of about this owl that’s kind of lonely and has made friends. I think of it as kind of a sweet story. And then there are other stories that do have a moral. That unevenness feels good to me. I have no idea what other people think.

Chapter 16: I’ve read that you refuse to read reviews of your books, and I’ve read articles where you’ve told the interviewer outright that you hate yourself.

Sedaris: That I hate myself? Really?

Chapter 16: Yeah, you don’t?

Sedaris: Today, I’m okay.

Chapter 16: Good; that makes me feel a lot better. I was going to say that maybe you ought to start reading your reviews, because then you would feel really good about yourself. People love you.

Sedaris: I always feel like I have kind of an unfair advantage because I was on the radio. When you’re on the radio, people feel like you’re speaking directly to them, so there’s an intimacy that you share with your listeners. With Garrison Keillor, it’s the same way. I feel a closeness with Garrison Keillor. He has no idea. We’ve never met or anything, but I feel about him differently than I feel about a writer I’ve never heard on the radio. Tobias Wolff—I love Tobias Wolff. But there’s not that intimacy there. I think when you are on the radio, you have an unfair advantage.

There are plenty of people who are much better writers, who deserve better, wider audiences. That’s one thing about going on tour that I enjoy. On this tour I’ve been recommending Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned by Wells Tower.

Chapter 16: I’ve been to several of your readings, and I know you always take a moment on tour to recommend another writer whose work you really love. You even have those books available for sale next to your own books.

Sedaris: This book is a joy to recommend. I’ve been reading out loud from it, and it just flies off that table. Some books are a harder sell. I never hold up my own book to give people a reason to buy it, but I’m actually pretty good about doing it with other people’s books. And that makes me feel a little bit better. I did have an extra advantage, but then when you can use that extra advantage to try to get a wider readership for people who you think deserve it, that makes it a little easier.

Sedaris: This book is a joy to recommend. I’ve been reading out loud from it, and it just flies off that table. Some books are a harder sell. I never hold up my own book to give people a reason to buy it, but I’m actually pretty good about doing it with other people’s books. And that makes me feel a little bit better. I did have an extra advantage, but then when you can use that extra advantage to try to get a wider readership for people who you think deserve it, that makes it a little easier.

Chapter 16: I was in the audience in Nashville several years ago, and you happened to mention that you’d read Bel Canto by Ann Patchett, and I don’t think I’ll ever forget the look on your face when you realized she was actually sitting in the audience.

Sedaris: Yeah, I didn’t realize that. I didn’t know anything about it when I got it, and it’s just such a good [book]. And I had no idea that she was there.

Chapter 16: Have you branched into fiction yourself in part because you’ve already mined the vein of childhood stories as far as it would go?

Sedaris: No, not really. There’s a couple stories that I took on this tour with me—they’re not childhood stories, but they’re stories about my life; they’re essays. One takes place in North Carolina in 1980; one took place over the summer, in France. But no. I think I wrote the first of these stories seven years ago. And I remember thinking I could write a few of these a year, put them in a pile, and then eventually make a book out of them. So that’s what I did.

Another thing I’ve been reading on this tour … I don’t know what to call it. I just call it a whimsy. It’s kind of like the [piece on] undecided voters. And it’s about Proposition 8 in California. I always like to have a little piece of political satire to bring on my tour, but it’s nothing that I can [include in a collection] later. If I were to collect them later, you’d think, “Did he just say ‘Bob Dole’?” Because it’s political, it dates much easier, and the [stories in the new book] didn’t necessarily date, so these were things that I could write [over time]. I kind of am doing another book the same way—a kind of “throw it on the pile” book.

Chapter 16: What is it?

Sedaris: Every time I go on tour, I read from my diary for ten or fifteen minutes. And it’s hard finding things that work. They have to work a certain way. They can’t be too long. I can go back through the year 1987—through the entire diary—and find like five things that might work. And then of those five, maybe three of them will actually work when I read them out loud. So I always bring a bunch [of new diary entries] on tour with me. I bring at least ten new things on tour with me, and of the ten I brought on this tour, four were gold. And then I’ve had two things happen on this tour that I wrote about, and they were just gold. So let’s say in a given year I might write fifteen that work, so I just put them on the pile. Eventually I can have a book of diary entries that work.

Chapter 16: I guess I’ve misunderstood your process all this time. I thought you were taking all these notes—keeping that little notebook with you all the time—because you went back through the diary to find the things that you could re-work into essays.

“So this girl had this really ugly t-shirt. It had these slashes of muddy color on it, and she asked me if I would sign it. And she said, ‘It was painted by a dolphin.’ And her mother added, ‘A dolphin with scoliosis.’ So it was just beautiful: a dolphin with scoliosis is out there painting t-shirts. That’s, that’s beautiful.”

Sedaris: There was a story that I had in The New Yorker a couple months ago. It was called “Standing By.” But before that was a story, [it started out as] diary entries. The flight attendant told me about crop dusting. Then I met a male flight attendant who told me about the thing where [they say, at the end of the flight], “Your trash, you’re trash.” So that was two diary entries. And I had another diary entry about hearing the paging of Hitler at the airport. But those were just incidents. None of them was a story. And then when I got held up in that long line in Denver, I thought, “I bet I could stitch those diary entries to this, and make it a story.” So a lot of times, the diary things, maybe they could work in a story later on.

Chapter 16: But for now the best ones go in the pile.

Sedaris: Yeah. Oh, a girl last week … . You know, I don’t really believe in signing things.

Chapter 16: You mean signing something besides a book?

Sedaris: Right. Like when people say, “Will you sign my hand?” It’s just embarrassing to do that. But I’m just so grateful that teenagers come [to my readings] that sometimes I see what I can do. So this girl had this really ugly t-shirt. It had these slashes of muddy color on it, and she asked me if I would sign it. And she said, “It was painted by a dolphin.” And her mother added, “A dolphin with scoliosis.” So it was just beautiful: a dolphin with scoliosis is out there painting t-shirts. That’s, that’s beautiful.

Chapter 16: Did you sign it?

Sedaris: Yeah, yeah. But I bet I’ll use that for something. I guess there’s a danger that I put it into this book of diary entries, and then I decide to use it later. People might say, “Wait a minute, I already read about this.” But, eh, that’s a chance I’m going to take.

Chapter 16: When did you start keeping a diary?

Sedaris: When I very first started, I was twenty. For the first few months I was just writing on the back of menus… diners and stuff. And then I got myself one of those hard-covered sketch books. And then, when I went to the Art Institute, I started typing my diary on eight-by-nine-and-a-half sheets of paper. And then I would put a picture—not every day, but a lot of days I would put a picture—and then I’d make a special cover for it, and I’d take it somewhere and have it spiral-bound. And I would do one for every season.

I’ve pretty much kept that formula. Now I use metal spiral bindings instead of plastic, and I don’t have as many pictures, but I always make a cover for it. Actually, I’ve never let anyone read my diary, and I would die if they did. But they’re nice objects. The covers are really beautiful. Sometimes I would find a painting in a thrift shop, and I would cut it down to eight-by-nine-and-a-half inches. And my boyfriend is a really good painter, and so I would just say, “Hugh, would you paint me like a squirrel for my fall diary cover?” and he’d do it. They’re very beautiful, so I have a cabinet that I keep them in. When I die they’ll go to Hugh, because Hugh doesn’t want anybody to read them either. But they’re pretty.

I’ve pretty much kept that formula. Now I use metal spiral bindings instead of plastic, and I don’t have as many pictures, but I always make a cover for it. Actually, I’ve never let anyone read my diary, and I would die if they did. But they’re nice objects. The covers are really beautiful. Sometimes I would find a painting in a thrift shop, and I would cut it down to eight-by-nine-and-a-half inches. And my boyfriend is a really good painter, and so I would just say, “Hugh, would you paint me like a squirrel for my fall diary cover?” and he’d do it. They’re very beautiful, so I have a cabinet that I keep them in. When I die they’ll go to Hugh, because Hugh doesn’t want anybody to read them either. But they’re pretty.

Chapter 16: They’re one-of-a-kind things. We had this gigantic disaster in Middle Tennessee last spring, and thousands of people lost everything in the flood. When you hear stories like that, does it make you nervous about your diaries?

Sedaris: Ten years ago I started writing my diary on my computer, so now I print it out at the end of every month. So if there was a fire, I would lose everything before 2000. I’d have lost twenty-two years of diaries. So, yeah, that would be bad. And I would lose all those paintings that Hugh did, so that would be bad, too.

Chapter 16: Let’s talk about something pleasant, then. What was it like to work with Ian Falconer?

Sedaris: Ian and I met in New York. When they put The Santaland Diaries on stage, Ian did the sets. The entire thing was a fiasco except for Ian’s sets. And his sets were fantastic. I remember I went to his apartment, and his niece had just been born, and her name was Olivia; he was thinking of doing a children’s book for her, and he had these drawings of a pig. And that turned into Olivia. He’s sold a jillion books since then, but he hasn’t changed a bit.

And then he and I did a project for Art Spiegelman—it was called Little Lit. They were comics for kids, and they teamed up writers with illustrators. And then we just always wanted to do something again. So he was my first choice. And I was just delighted that he agreed to do it.

Chapter 16: Did you give him any guidance about the kind of pictures you had in mind for the book?

Sedaris: I figure you either choose the right person or you don’t. You choose somebody and then you treat that person like an artist. I didn’t want to say, “Ian, can we be a little more playful with that?” He kept saying to me, “If there’s anything that you don’t like; if there’s anything that bothers you … .” And the drawing he did of the rabbit was a lot fluffier than what I had in my mind, so he caused the rabbit to lose like twenty pounds. He said, “Is there anything that you want to see a picture of?” And I said, “Well, I wouldn’t mind seeing that hairless mink.” I wish I hadn’t even said that. I bet if I had left that to Ian, he would have come up with something better. You don’t want to try to control things when the person you’re working with is better at the thing than you are.

When I announced that there were going to be illustrations in the book, a lot of people sent me their stuff. I kind of already knew who I wanted, but you want to be polite and so you look at it. But a lot of the other people were kind of amateurs—this is something they wanted to do, but they had never done it before. I don’t think that they quite understood that the illustration is something you’re going to turn back to. You’re going to start reading the story, and then you’re going to turn back to the illustration and see it in a different way, mid-way through the story. And you might turn back again at the end of the story. Ian had a real understanding of that.

When I announced that there were going to be illustrations in the book, a lot of people sent me their stuff. I kind of already knew who I wanted, but you want to be polite and so you look at it. But a lot of the other people were kind of amateurs—this is something they wanted to do, but they had never done it before. I don’t think that they quite understood that the illustration is something you’re going to turn back to. You’re going to start reading the story, and then you’re going to turn back to the illustration and see it in a different way, mid-way through the story. And you might turn back again at the end of the story. Ian had a real understanding of that.

Chapter 16: This book is not for children. The pictures by Ian Falconer might be a little misleading if you don’t know anything about David Sedaris, and you’re just looking at the cover of the book as an Ian Falconer fan. Do you think you’ll do a real children’s book together someday?

Sedaris: I’m the only person in the world who doesn’t think he’s going to write a children’s book. You know how everybody thinks they can do it? I don’t. I had something on This American Life years ago, and it was a poem about a dog who goes to court. It was called “Kathleen on the Carpet.” And a children’s-book editor contacted me, and said, “I heard the thing on the radio, and I think it would make an excellent children’s book.” And I said, “Well, actually, it wouldn’t. It’s like a fifth-rate Dr. Seuss rip-off, and it wouldn’t make a good children’s book at all.” [But he said,] “I know what I’m talking about—this is my business. I think this would make a good children’s book.” I said, “Really, you just didn’t hear it correctly.” Anyway, he asked me like three times to send it to him, so I sent it to him. And he sent me a form rejection letter.

There are people who write children’s books who are really good at it, [but] I just don’t know enough about them. I like children, but I don’t think that’s good enough.

Chapter 16: You’re a fan of audiobooks. Do you approve of the audiobook of Squirrel Seeks Chipmunk?

Sedaris: Well, I’m actually a producer because I picked the people who were going to read it, and I picked the person who did the music. But anyway, Elaine Stritch is one of the readers on the audio book, and she does a great job. I feel like doing the audio that way was kind of like having the book illustrated. The illustrations were Ian interpreting the stories, and the audio book were the actors interpreting the stories. Siân Phillips, who played Livia on I, Claudius, is one of the readers. She read “The Squirrel and the Chipmunk.” I was in the studio in London when she recorded it, and I certainly did not tell her what to do. I had read these stories so many times, and I had in my mind the way that they would go. But who ever said my way was right? I mean, I would listen to her, and listen to Dylan Baker and Elaine Stritch—just the way that they interpreted the stories—and I would think, “That’s what that story is about. I never knew what that story meant—I never knew what it was about until they showed me.”

I love books on tape. I added another story for the audio book. It’s about shit- and vomit-eating flies. I read the story one night in California, and this woman said, “I’m sorry, but I just ate, and it was just hostile [of you] to read that story.” I mean, if it was about children who eat shit and vomit, then OK, but what do you think flies eat? What do you expect of a fly?

David Sedaris will read from and sign copies of Squirrel Seeks Chipmunk at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Memphis on November 13 at 3 p.m.