Dark Lantern

An author finds his own teenage ghost in a thrift-shop book

Past the thrift-shop racks of musty shirts and jeans, beyond a junkyard of orphaned kitchen utensils, I was prowling the few shelves of books, hoping for treasure at a dollar a book. It was the day before Halloween 1993 at the Nashville Goodwill store. Nearby, two college-age women who looked as if they had been born in expensive clothing were chuckling over the hobo garb they might snag for a Vanderbilt costume party. Distantly enjoying their clueless but not cruel banter, I was scanning the bookshelves, left to right, top to bottom, when I felt the hair stand up on the back of my neck.

A ghost was nearby—myself as a young boy. What my eyes noticed and my instinct recognized before alerting my conscious mind was a fat textbook whose nerdy bulk shouldered aside jacketless volumes gold-stamped Danielle Steele and Dean Koontz.

What I saw was not a dusty old book but a teenage boy in a wheelchair by a window in a ramshackle house farther east in Tennessee—two hours away, on the Cumberland Plateau near Crossville. I was born in this house in 1958, grew up in it, learned to read in it, learned about animals from it. The window showed a rocky backyard garden. On a small hill beyond, oak-and-hickory woodland crowded the mown grass. The room held a small bed, bookcases, and a lamp on a rickety table absurdly made from the leaf of a Formica kitchen table. Late afternoon, with an autumn sunset gilding even the cheap, mismatched bookshelves.

That boy in memory was reading the same middle-school-level literature book I had just found on the Goodwill shelves—Outlooks through Literature, whose spine bore the names Pooley, Stuart, White, and Cline. On its cover was an ugly sepia photograph of men and women silhouetted within the arches of what appeared to be a two-story bridge. Seated in a wheelchair at fourteen, standing in a thrift store at thirty-five, I turned familiar-feeling pages to a Contents list whose items inspired affection that ran like a herald before a montage of memories:

Unit One, The Short Story

Unit Two, Biography and Autobiography

Unit Three, A Book of Poetry

Unit Four, Romeo and Juliet

Unit Five, Classical Heritage

Unit Six, A Tale of Two Cities

Unit Seven, At Random

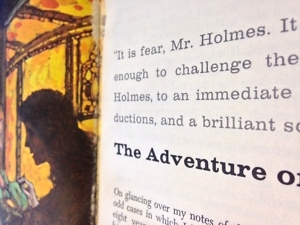

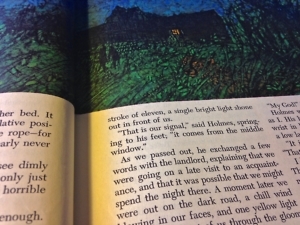

Unit One opened with “The Adventure of the Speckled Band” by Arthur Conan Doyle, which I now know was among the first Holmes short stories after two novels. It was also the beginning of my own fascination with Victorian fiction. “‘It is fear, Mr. Holmes. It is terror,’” I read at the top of the page. “These words were enough to challenge the Master Detective, Sherlock Holmes, to an immediate investigation, some rapid deductions, and a brilliant solution.” Facing it on the left, a colorful full-page illustration portrayed a woman in what appeared to be stages of collapse.

I think this was my first encounter with Sherlock Holmes as a character in a book rather than as distilled mannerisms in a TV movie. I think of this story as the wardrobe that opened into Narnia, the tornado that whirled me to Oz. It drew me into the Holmes stories, and thence into the larger world of Dickens and Eliot, Austen and Darwin. Standing in Goodwill, I felt my cheeks tug into a smile as I glanced at the footnotes illuminating terms likely to baffle U.S. students: dogcart, Waterloo, Bengal Artillery, dark lantern—a lamp that has a movable panel to hide its light, which has always struck me as confusingly metaphorical. I may have met Holmes earlier, thanks to my lepidopteran instinct to sniff every book in the garden, but if so it must have been on a page lacking the baited scent of illustrations and footnotes.

I think this was my first encounter with Sherlock Holmes as a character in a book rather than as distilled mannerisms in a TV movie. I think of this story as the wardrobe that opened into Narnia, the tornado that whirled me to Oz. It drew me into the Holmes stories, and thence into the larger world of Dickens and Eliot, Austen and Darwin. Standing in Goodwill, I felt my cheeks tug into a smile as I glanced at the footnotes illuminating terms likely to baffle U.S. students: dogcart, Waterloo, Bengal Artillery, dark lantern—a lamp that has a movable panel to hide its light, which has always struck me as confusingly metaphorical. I may have met Holmes earlier, thanks to my lepidopteran instinct to sniff every book in the garden, but if so it must have been on a page lacking the baited scent of illustrations and footnotes.

Even scanning quickly, I recalled this uninviting typeface, the antique illustrations, the bulk of 754 pages meant to be traversed during a school year. The endpapers bore a rubber-stamped JOHN GLENN HIGH SCHOOL and a Michigan address. One of the things I love about used books is their archaeological clues to other lives—shards such as Merry Christmas, Joey, from Aunt Charlotte or a ticket stub marking the last campsite toward the summit before a reader gave up and started back downhill.

Browsing these pages in Goodwill, I found a distinctive aspect of Outlooks through Literature that I had forgotten: extra flourishes around the author bio at the end. Obsessed—almost from birth, it seems now—with how books were created, I had always read author and illustrator biographies, “By the Same Author” pages, acknowledgments, and source notes. In revisiting this book I found, beginning an inch below Holmes’s explanation to Watson of how he had nudged Dr. Roylott to his grisly death, a section entitled “Could This Really Have Happened?”

There I found the results of a careful study by W.T. Williams, “a British naturalist,” who determined that there was no such snake as the swamp adder of the story, and that many of its antics no snake could perform. Then came questions under “What Do You Say?” and “Author’s Craft,” a note about prefixes under “Know Your Words,” and a paragraph about Conan Doyle. These extras were like windows on the rear of a house, showing tantalizing glimpses of the building through whose back door I had just emerged. It seems to me now, twenty-four years after finding this book in Goodwill and twenty years after the publication of my own first book, that I spend most days peering through windows into the pantries and tool sheds of stories to see how they are made.

In late 1971, halfway through the eighth grade, I dropped out of regular school and began studying with “homebound” teachers who came to the house three afternoons a week. I suffered from increasing leg and back and joint pain, which was later diagnosed as juvenile rheumatic arthritis, blamed on a bout of rheumatic fever. Arthritis had finally earned me my own room—in the back, overlooking garden and woods. My bed was no more than ten feet above the cellar, with its spider-webbed wooden shelves fitted into dirt, its dusty Mason jars and frogs declaiming from the frequent standing water. My younger brother slept in the front room—where I was born during a snowstorm—with only a curtain at the doorway. So many memories wafted from this volume.

In late 1971, halfway through the eighth grade, I dropped out of regular school and began studying with “homebound” teachers who came to the house three afternoons a week. I suffered from increasing leg and back and joint pain, which was later diagnosed as juvenile rheumatic arthritis, blamed on a bout of rheumatic fever. Arthritis had finally earned me my own room—in the back, overlooking garden and woods. My bed was no more than ten feet above the cellar, with its spider-webbed wooden shelves fitted into dirt, its dusty Mason jars and frogs declaiming from the frequent standing water. My younger brother slept in the front room—where I was born during a snowstorm—with only a curtain at the doorway. So many memories wafted from this volume.

About the same time as my original encounter with this textbook, I spent a stormy night at Erlanger Hospital in Chattanooga. The next morning I was scheduled for an early spinal tap—the most horrific experience of my life up to then and still a milestone of agony that makes me cringe.

I was in a ward with three old men. One of them was at some point shaved with a dry scraping noise, and one of them died during the night. The only TV on the floor was in a waiting room down the hall. During a fierce thunderstorm someone pushed my wheelchair down there, where we watched The Hound of the Baskervilles—Stewart Granger as a pallid old Sherlock Holmes and William Shatner as George Stapleton. This version first aired on ABC in February 1972, the month I turned fourteen, but it must have been run again later because my memory takes place during a summer thunderstorm. And of course you can always trust memory.

During the broadcast, a close flash of lightning was followed by a power outage. Soon, no doubt, the power returned, but my memory stops with the lightning and the demise of the TV screen. I don’t recall getting to see the rest of the movie before going back to my room, where soon I woke to a nurse’s discovery of the old man’s death. I do remember lying in that bed, staring at the ceiling after they wheeled him out, feeling my own pulse ticking like a bomb, thinking about my father’s heart attack at thirty-eight, when I was three, and of my mother’s breakdown.

Because I note on its flyleaf the date on which a book enters my life, I see that the year after Erlanger, on the sixteenth of December 1973, I received the two fat volumes of William S. Baring-Gould’s The Annotated Sherlock Holmes from a mail-order book club called the Mystery Guild. They contained the species of footnotes and sidebars found in Outlooks through Literature, but these glosses opened up to a tropical profusion of research and speculation: illustrations of hansom cabs, meditations on the super-villain snake of “Speckled Band,” biographies of illustrators. I stayed up almost all night after it arrived in the mail.

Because I note on its flyleaf the date on which a book enters my life, I see that the year after Erlanger, on the sixteenth of December 1973, I received the two fat volumes of William S. Baring-Gould’s The Annotated Sherlock Holmes from a mail-order book club called the Mystery Guild. They contained the species of footnotes and sidebars found in Outlooks through Literature, but these glosses opened up to a tropical profusion of research and speculation: illustrations of hansom cabs, meditations on the super-villain snake of “Speckled Band,” biographies of illustrators. I stayed up almost all night after it arrived in the mail.

As I stood before those Goodwill bookshelves in 1993, I was still two years away from my first publishing deal, for a book of days called Darwin’s Orchestra: An Almanac of Nature in History and the Arts. In its index I find nine entries on “Holmes, Sherlock (fictional character).” Twenty-four years and fifteen books down the road, I see that the Sherlock Holmes stories were more important to me than I had realized even as the textbook stirred memories of their discovery. They helped enchant literature for me, and notes about their origin opened a window into formerly opaque history. I never became a fanatical Sherlockian. I haven’t joined the Baker Street Irregulars. But Doyle and Holmes introduced me to a number of perennial interests I found so entertaining that ultimately I built a career around them.

I have edited seven anthologies of Victorian fiction—with, to show the legacy of that textbook, titles such as The Penguin Book of Victorian Women in Crime: Forgotten Cops and Private Eyes from the Time of Sherlock Holmes. Again and again, as I wrote my most recent nonfiction book, Arthur and Sherlock: Conan Doyle and the Creation of Holmes, I found myself in the emotional terrain of that first encounter and in the nerdy landscape of literary research that the book’s footnotes and illustrations inspired.

In the way that literature and life distill experience into essence, this turf has become a site for discovery and adventure, not a place of pain or fear or loss. Those aspects of my childhood have seeped into its soil and perhaps nourish it, but they no longer flower. In waking my imagination and curiosity, Holmes and Watson gave me the possibility of growing up to live in a larger world—a world first reached through London’s mythic cobblestones and fog, which could be navigated even from a wheelchair.

[This article originally appeared on 12/4/2017.]

Copyright (c) 2017 by Michael Sims. All Rights reserved. Michael Sims is the author of The Story of Charlotte’s Web, which The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, and other publications chose as a best book of the year; Adam’s Navel, which was a New York Times Notable Book; The Adventures of Henry Thoreau; and other books. He edits The Connoisseur’s Collection series of Victorian anthologies, including Dracula’s Guest, The Dead Witness, The Phantom Coach, and Frankenstein Dreams. A Crossville native, he lives in Western Pennsylvania