Daughters, Lost and Found

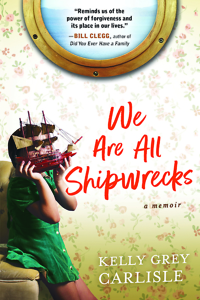

In We Are All Shipwrecks, Kelly Grey Carlisle writes about her eccentric family and the legacy of a violent crime

What’s a normal childhood? How do we come to know who we are? What does a happy ending look like? Those questions are at the heart of Kelly Grey Carlisle’s We Are All Shipwrecks, a memoir of growing up in an eccentric family and carrying the legacy of a violent crime. Carlisle delivers an often bleak story with a kind of skillful tenderness, and in the process she explores the power and limitations of love.

The bare outline of Carlisle’s childhood story is equal parts lurid, sad, and absurd. Her twenty-three-year-old mother, Michele, was murdered in 1976, when Carlisle was just three weeks old. The infant was found nestled in a dresser drawer at the Hollywood motel where Michele, who was estranged from her family, had been staying. After spending four years with Michele’s mother, little Kelly was adopted by Michele’s British-born father and his much younger wife, who together ran a profitable Los Angeles porn store and video arcade. Richard Grey—or Sir Richard, as he styled himself—dreamed of life on the open sea and soon insisted on lodging the whole family aboard a boat that was perpetually in need of repair and docked at a seedy marina. Carlisle grew up there, surrounded by a collection of washouts and misfits.

The bare outline of Carlisle’s childhood story is equal parts lurid, sad, and absurd. Her twenty-three-year-old mother, Michele, was murdered in 1976, when Carlisle was just three weeks old. The infant was found nestled in a dresser drawer at the Hollywood motel where Michele, who was estranged from her family, had been staying. After spending four years with Michele’s mother, little Kelly was adopted by Michele’s British-born father and his much younger wife, who together ran a profitable Los Angeles porn store and video arcade. Richard Grey—or Sir Richard, as he styled himself—dreamed of life on the open sea and soon insisted on lodging the whole family aboard a boat that was perpetually in need of repair and docked at a seedy marina. Carlisle grew up there, surrounded by a collection of washouts and misfits.

But the truth of Carlisle’s experience, as she recounts it in a voice that’s both quiet and compelling, was far more complex than these biographical facts suggest—grim in many ways, yes, but also filled with love and good intentions that were at least partly fulfilled. Marilyn, Richard’s wife, was deeply unhappy but loved her adopted child with as much passion as any mother could, and Carlisle remembers her maternal grandmother, Spence, as a devoted parent, too. Spence’s longtime companion, Dee, and several denizens of the dock also cared for and about the little girl with real openheartedness. Carlisle writes about all these surrogate parents and caregivers with gentle, clear-eyed gratitude. One of the driving motivations for the memoir, in fact, seems to be her desire to thank the many people who “helped raise a child not their own.”

The troubling and fascinating presence in Carlisle’s story is Richard, a difficult character who seems to dominate the lives of everyone around him. Affectionate, magnanimous, and capable of great charm, he was also tyrannical, abusive, grandiose, and profoundly selfish. He was protective enough to send his granddaughter to a first-rate private school, yet he was also apparently oblivious to the less-than-wholesome environment the family lived in and the risks it might involve for a young girl. Not one to let the truth get in his way when it was inconvenient or unsatisfying, he offered up an edited and embellished version of family history that took Carlisle years to correct.

The troubling and fascinating presence in Carlisle’s story is Richard, a difficult character who seems to dominate the lives of everyone around him. Affectionate, magnanimous, and capable of great charm, he was also tyrannical, abusive, grandiose, and profoundly selfish. He was protective enough to send his granddaughter to a first-rate private school, yet he was also apparently oblivious to the less-than-wholesome environment the family lived in and the risks it might involve for a young girl. Not one to let the truth get in his way when it was inconvenient or unsatisfying, he offered up an edited and embellished version of family history that took Carlisle years to correct.

At the center of that history is the life and death of Michele. As the book unfolds, Carlisle’s understanding of her mother’s fate, as well as her own, slowly evolves as she begins to see that her grandfather’s words couldn’t necessarily be taken at face value. When, at age eight, she finally learns that Michele was murdered, possibly by the infamous Hillside Strangler, she tries to figure out how this fact affects her own place in the world. ”A secret part of me had always wanted to be special,” she recalls. “Now I was, and I couldn’t decide if it felt good or not.” The book is filled with poignant moments like this one, with Carlisle entering the mind of the child she was, struggling to understand.

In some of the book’s most powerful passages, Carlisle writes about the way her mother’s murder, the family porn business, and her grandfather’s habit of sharing far too much about his own sexual disappointment had a damaging effect on her budding sexuality. Violence and love became linked in her mind, even in her fantasies about Michele’s death:

Her death certificate says she was found at 8:10 a.m., and so I always pictured her an hour or so before she was found, in the quiet hush of morning that can happen even in L.A. I always tried to give her a little beauty before I got to the hardness of her death: sun shining through beads of dew on a blade of grass, a ladybug, a birdsong, and then … I imagined purple bruises around her neck, her lips torn, rope burns around her wrists, her eyes, hazel like mine, filled with hate.

We Are All Shipwrecks takes Carlisle, a Sewanee graduate, into a successful adulthood and an eventual resolution of some of the lingering mysteries about her mother, but the book focuses primarily on her childhood and teen years, and brilliantly so. Though the story is told with adult insight, the perspective is a youngster’s, and it’s delivered with all the freshness and sharpness of early experience. Richard, Marilyn, and the coterie of marina characters are depicted as a child would encounter them, with all their messy contradictions unreconciled. And although the grown Carlisle, looking back, must reckon with a lot of human failings in those she loved, she does so with such generosity of spirit that her story becomes redemptive, even beautiful.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College, she has attended the Clothesline School of Writing in Chicago, the Moss Workshop with Richard Bausch at the University of Memphis, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. She lives in White Bluff.