Dispatches from the Default Period

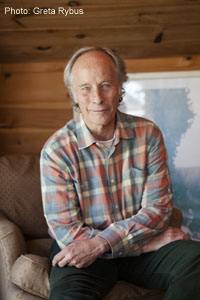

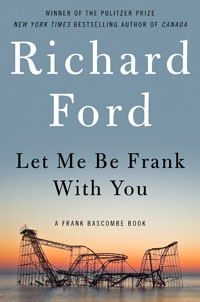

In Richard Ford’s new volume of novellas, Let Me Be Frank With You, Frank Bascombe returns to reflect on life’s final act

Despite a body of work that traverses a broad landscape of American character and experience, Richard Ford will always be recognized first as the creator of Frank Bascombe, American Everyman, who first appeared in The Sportswriter (1986). That quietly momentous novel was Ford’s third; the first two garnered such scant attention that he briefly gave up on fiction writing for a career as, you guessed it, a sportswriter. The Sportswriter elevated Ford from the remainder bins to the status of generational spokesperson. A sequel, the PEN/Faulkner- and Pulitzer Prize-winning Independence Day (1995), cemented Ford as a literary institution and Frank Bascombe as an iconic American voice. The third volume, The Lay of the Land (2006), relocated Frank to a spacious seaside house on the Jersey Shore. Upon its publication, Ford announced that we had heard the last of Frank Bascombe.

Always mercurial and unpredictable—“a writer of jangling personal fascination to many in the literary world,” according to Lorrie Moore—Ford has broken his promise with his new book, Let Me Be Frank With You, a decision for which his many readers will be unanimously thankful. A comparatively slim volume, this brace of loosely connected stories serves as a sort of ruminative dispatch from our old pal Frank in the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy—a status update, you might say, if Frank Bascombe were on Facebook. (“I’m not, of course,” he assures us. “Though both my wives are.”)

Always mercurial and unpredictable—“a writer of jangling personal fascination to many in the literary world,” according to Lorrie Moore—Ford has broken his promise with his new book, Let Me Be Frank With You, a decision for which his many readers will be unanimously thankful. A comparatively slim volume, this brace of loosely connected stories serves as a sort of ruminative dispatch from our old pal Frank in the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy—a status update, you might say, if Frank Bascombe were on Facebook. (“I’m not, of course,” he assures us. “Though both my wives are.”)

The first story, “I’m Here,” opens with Frank in retirement, “a member of the clean-desk demographic.” He takes a call from the man to whom he and his second wife, Sally, sold their seaside love nest eight years earlier, when they decided to move inland. Having seen the disaster footage on CNN, Frank already knows why the man is calling him: the house has been destroyed—literally blown off its foundation. The unfortunate homeowner wants Frank’s advice, but Frank knows that what he really wants is to vent, or even to lay blame on the guy who was lucky enough to sell at the peak of the market, making a tidy profit and conveniently escaping disaster.

As usual, Frank is philosophical and even-handed about it: “You bear some responsibility to another human you sell a house to. Not a financial one. Conceivably not a moral one. But one in which, even rarer, the professional and human operate on a single set of rails. A priestly, vocational responsibility.” Could anyone else but Frank Bascombe so elegantly raise realtors to the status of spiritual counselors?

Having survived his bout with prostate cancer and rebuilt his second marriage—outcomes both still faintly uncertain at the conclusion of The Lay of the Land—Frank has entered what he calls the “Default Period” of life. Comfortably inland, the bucolic town of Haddam has been spared the brunt of Sandy’s ravages, but the physical and human detritus are everywhere. Sally is mostly offstage in this volume, serving as a volunteer grief counselor for those left bereft and displaced in the wake of the storm, leaving Frank alone with plenty of time for pensive musings and sharp critiques of life’s absurdities. “I’m only here on the sidelines and not, in my opinion, suffering any evident grief,” Frank remarks. “The natural inclination would be to suspect that I’m either irrelevant, or that I’m suffering an even worse grief than anyone knows. Or third, that I’m a malcontent who has too much time on his hands and needs to find better ways to be useful. Determining which of those is true isn’t so easy in any life.”

Having survived his bout with prostate cancer and rebuilt his second marriage—outcomes both still faintly uncertain at the conclusion of The Lay of the Land—Frank has entered what he calls the “Default Period” of life. Comfortably inland, the bucolic town of Haddam has been spared the brunt of Sandy’s ravages, but the physical and human detritus are everywhere. Sally is mostly offstage in this volume, serving as a volunteer grief counselor for those left bereft and displaced in the wake of the storm, leaving Frank alone with plenty of time for pensive musings and sharp critiques of life’s absurdities. “I’m only here on the sidelines and not, in my opinion, suffering any evident grief,” Frank remarks. “The natural inclination would be to suspect that I’m either irrelevant, or that I’m suffering an even worse grief than anyone knows. Or third, that I’m a malcontent who has too much time on his hands and needs to find better ways to be useful. Determining which of those is true isn’t so easy in any life.”

These stories serve as a series of meditations on an aging Baby Boomer’s creeping malaise. Frank putters around the house, and joins a group of older vets once a week to greet soldiers returning from Afghanistan and Iraq. He pays regular visits to his ex-wife, Ann, now relocated to a luxury nursing home in Haddam after her Parkinson’s diagnosis. Friends have begun to die off. Children are geographically and emotionally distant. The daily reminders of advancing age stimulate—in a painstaking observer like Frank, anyway—an acute awareness of the pathos of life at a time when the end is in sight but not yet imminent. “Am I the only human who occasionally thinks that he’s dreaming?” Frank asks. “I think it more and more.”

Regardless of its somewhat funereal context, Let Me Be Frank With You contains many moments of levity, even hilarity. Frank has always had a flair for mordant humor in his dissection of—well, almost anything. Take, for instance, his assessment of his ex-wife’s nursing home beau: “Buck’s a large, dull piece of cordwood in his seventies, given to loose-fitting permanently-belted trousers, matching beige sweatshirts of the kind sold at Kmart, big galunker, imitation-suede shoes, and the thinnest of thin pale hosiery. Somewhere, someone convinced Buck that a sculpted ‘imperial’ and a pair of black horn-rimmed Dave Garroway specs would make him look less like a Polish meatball, and make people take him more seriously, which probably never happens.”

This comic mockery tempers but does not overwhelm the book’s essential seriousness. Each story presents a striking set piece in which Frank must put his gently dogged optimism up against the fact of life’s persistent sorrow, indignity, and misfortune. A quietly regal woman named Mrs. Pine appears at Frank’s door; she lived in his house years earlier and slowly reveals the terrible truth of what happened there. A long forgotten friend dying of cancer calls Frank to his bedside to make a startling confession. Ann, Frank’s ex, contemplating her advancing Parkinson’s disease, asks Frank’s opinion of assisted suicide. “I think these things are surrounding us all the time,” Ford said in a recent interview with NPR. “We don’t have experiences to get over [them]; we have experiences so we can sort of deal with them and address them and have, in some ways, some stability towards them.” It’s worth noting as well that Ann’s return to Haddam has nothing to do with Frank; she wants to be buried next to their first son, Ralph, whose death from Reye’s Syndrome decades earlier precipitated the end of their marriage and gave birth to the pensive voice of The Sportswriter.

“I’m departing. We both are,” Frank says, as he steps away from the bedside of his dying friend, echoing Walt Whitman, another contemplative soul who chose to live out the last of his days in suburban New Jersey. Still, one cannot help but leave the last of these haunting tales, which are somehow both bleak and comforting, with the sense that Frank Bascombe will have more to say before the soil reclaims him.

Ed Tarkington holds a B.A. from Furman University, an M.A. from the University of Virginia, and a Ph.D. from the creative-writing program at Florida State University. His debut novel, Only Love Can Break Your Heart, is forthcoming from Algonquin Books. He lives in Nashville.