Don't Chase It, And It Will Come Back

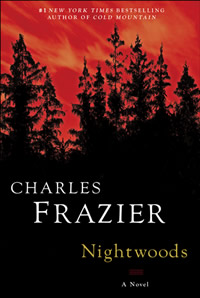

In Nightwoods, Charles Frazier has written a tender love story, a taut thriller, and a worthy successor to Cold Mountain

Early on in Charles Frazier’s Nightwoods, Luce visits Maddie, the nearest neighbor to the abandoned mountain-resort lodge Luce occupies as caretaker. Luce, a former cheerleader, is now a spinster and near-hermit, and Maddie is a similarly self-reliant old crone of indeterminate age still living a nineteenth-century lifestyle in the early 1960s. During the visit, she regales Luce with renditions of the ancient Appalachian Murder Ballads she has carried with her from the previous century. “They were dark-night songs,” writes Frazier. “Knocked-up girls got stabbed or shot or hit in the head, and then turned in the cold ground or thrown into the black deep river. Pretty Polly. Little Omie Wise. Go down, go down, you Knoxville Girl. Sometimes reproduction did not even factor into the narrative. The man snuffed the girl out because he could not own her, a killing offense if the girl’s opinions ran counter to his urges. In the ballads, love and murder and possession fit tight against one another as an outgrown wedding band on a swollen finger.” This final, harrowing image is all too appropriate to Nightwoods, a gorgeous, spellbinding novel in which the simultaneously devastating and healing powers of human passions are set in collision over the fate of a pair of damaged orphan children.

The girl and the boy—Dolores and Frank—arrive on Luce’s doorstep high in the mountains of Western North Carolina, disrupting Luce’s isolated but apparently contented existence looking after the abandoned resort lodge, whiling away the evenings reading from the library or listening to the radio. The children belong to Lily, Luce’s sister, who has recently become the victim of the kind of man sung about in Maddie’s ancient murder ballads. Sole witnesses to their mother’s murder at the hands of their step-father, Dolores and Frank have retreated into a damaged, feral domain of their own, communicating only with each other, often through violence. As Luce observes them fight, they remind her “of snakes fighting. Real cold, like they were not even very angry at each other, just acting under some shared compulsion as incomprehensible as sex or madness.” They express themselves to the outside world only through hunger and the urge to set things afire.

Luce has no desire to take them on—“she didn’t even really like the children, much less love them”—but does so out of obligation to her dead sister and resentment of her own mother, who abandoned them both to a hardscrabble life with their alcoholic, speed-addicted father, leaving them with only one lesson: “Never cry. Never ever.” Hence, a damaged family is formed at the edge of civilization, with Luce the self-appointed docent and accidental mother.

Luce has no desire to take them on—“she didn’t even really like the children, much less love them”—but does so out of obligation to her dead sister and resentment of her own mother, who abandoned them both to a hardscrabble life with their alcoholic, speed-addicted father, leaving them with only one lesson: “Never cry. Never ever.” Hence, a damaged family is formed at the edge of civilization, with Luce the self-appointed docent and accidental mother.

But no Eden—even (perhaps especially) one occupied by such broken souls—can linger too long safe from the reach of the serpent’s fangs. That inevitable, archetypal menace appears in the form of Johnny “Bud” Johnson, who, thanks to a slick trial lawyer and a bumbling rookie prosecutor, has walked away from the charge of having murdered Lily after she walked in on him in the midst of physically abusing her children. Before her death, it seems, Lily discovered a large cache of stolen money Bud had pilfered in a house burglary, hiding it where he could not find it. Bud is certain the cash has been delivered, along with Lily’s children, to her estranged sister. He aims to recover the money and, perhaps, to ensure the silence of the only witnesses to his most serious crime.

Though set in the early 1960s, Nightwoods is a story that could take place at almost any time—though, certainly, not in any place. For Charles Frazier, the landscape of western North Carolina is a character as important as any other. A former English professor, Frazier compulsively weaves myth, archetype, and allusion into the pages of his narratives, and the pleasures of period detail and exhibitions of encyclopedic knowledge of flora, fauna, and topography are amply on display. His elegant prose ranges from the lofty heights of poetic lyricism to the pitch-perfect antique diction of the Appalachian towns.

Nevertheless, Nightwoods presents a leaner, tighter version of Frazier’s elegant style than is on display in Cold Mountain or his second novel, Thirteen Moons. Even his early musings, easily cast off as beautiful window dressing, rise in significance as the novel reaches its final third. As the story speeds toward its harrowing climax, Frazier shifts the narration from past to present tense, intensifying the spiral of passion run amok like the rampant forests surrounding Luce’s mountain retreat.

Charles Frazier catapulted to fame in the late nineties thanks to the unlikely and extraordinary success of Cold Mountain. All of his work is characterized by patient plot development and gorgeously meticulous period detail. Frazier maintains a reverence for landscape and the synchronicity between human beings and their natural environments that few contemporary novelists seem either capable of or courageous enough to attempt in a literary publishing climate that presumes the audience is too fickle and superficial to appreciate the old stuff. Frazier’s elegiac, neo-biblical language, his weighty, frequently solemn turns of phrase, and his essentially tragic view of the human condition channel Faulkner via Cormac McCarthy and especially Toni Morrison, whose Beloved looms large over the characters of Luce and the mute, ruined children.

Charles Frazier catapulted to fame in the late nineties thanks to the unlikely and extraordinary success of Cold Mountain. All of his work is characterized by patient plot development and gorgeously meticulous period detail. Frazier maintains a reverence for landscape and the synchronicity between human beings and their natural environments that few contemporary novelists seem either capable of or courageous enough to attempt in a literary publishing climate that presumes the audience is too fickle and superficial to appreciate the old stuff. Frazier’s elegiac, neo-biblical language, his weighty, frequently solemn turns of phrase, and his essentially tragic view of the human condition channel Faulkner via Cormac McCarthy and especially Toni Morrison, whose Beloved looms large over the characters of Luce and the mute, ruined children.

Throughout his career, however, Frazier has broken from these influences in his tendency toward a Romanticism that, though perhaps sometimes a bit too cinematic and a tad contrived, manages to be entirely persuasive thanks to his gifts as a storyteller. At the center of each of his novels are pairs of lovers separated by time and circumstance, each longing for the other, convinced that the love between them can somehow heal a soul damaged by the random cruelty of an unmerciful world. Despite its Civil War setting and the dark shadow it casts on that history through the gruesome perils its protagonists must endure, Cold Mountain, for example, is at root a love story, with a fully realized heroine who, by its conclusion, is no mere damsel in distress. The Confederate deserter Inman risks everything to get back to his beloved Ada, the Charleston-bred preacher’s daughter he last saw in bonnet and hoop skirt. Meanwhile, Ada, hardened by grief and poverty, is in the process of becoming another creature entirely—so much so that, when the two finally reunite, they are, for a lingering moment, unrecognizable to each other.

In Nightwoods, through Luce, Frazier presents an inverse of Ada. Hardened from the outset, she is gradually softened as the children force her cares back to the world outside herself, and by the return of an old acquaintance who remembers her as she was before she sequestered herself in the abandoned mountain lodge: a carefree teenager parading through a local beauty show in a sleeveless one-piece, wearing a pair of green cat-eye sunglasses and snacking on a frozen Mars bar. “At that age, we’re mostly high-pitched and crazy. And that’s why we do dangerous and embarrassing things, as if simultaneously we’re immortal and going to die tomorrow,” Luce says, assuring herself more than anyone else that “I’m not the same person as that girl.” But her suitor assures her, “We are who we are. Ten or eighty. What we see in the mirror is all that changes. Same fears and hopes running around inside like hamsters on a wheel.” The spell Frazier casts in these images, heavy with longing and nostalgia, makes a strong case for a view of the world in which the beautiful may not necessarily be damned, despite their frailty and mortality.

Ed Tarkington will interview Charles Frazier about Nightwoods at the 2011 Southern Festival of Books, held October 14-16 in Nashville. The event, like all festival events, is free and open to the public.