Earth, Seedtime, Growth, and Harvest

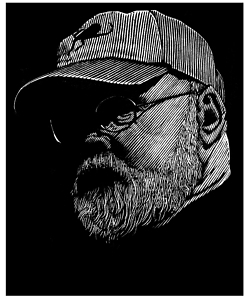

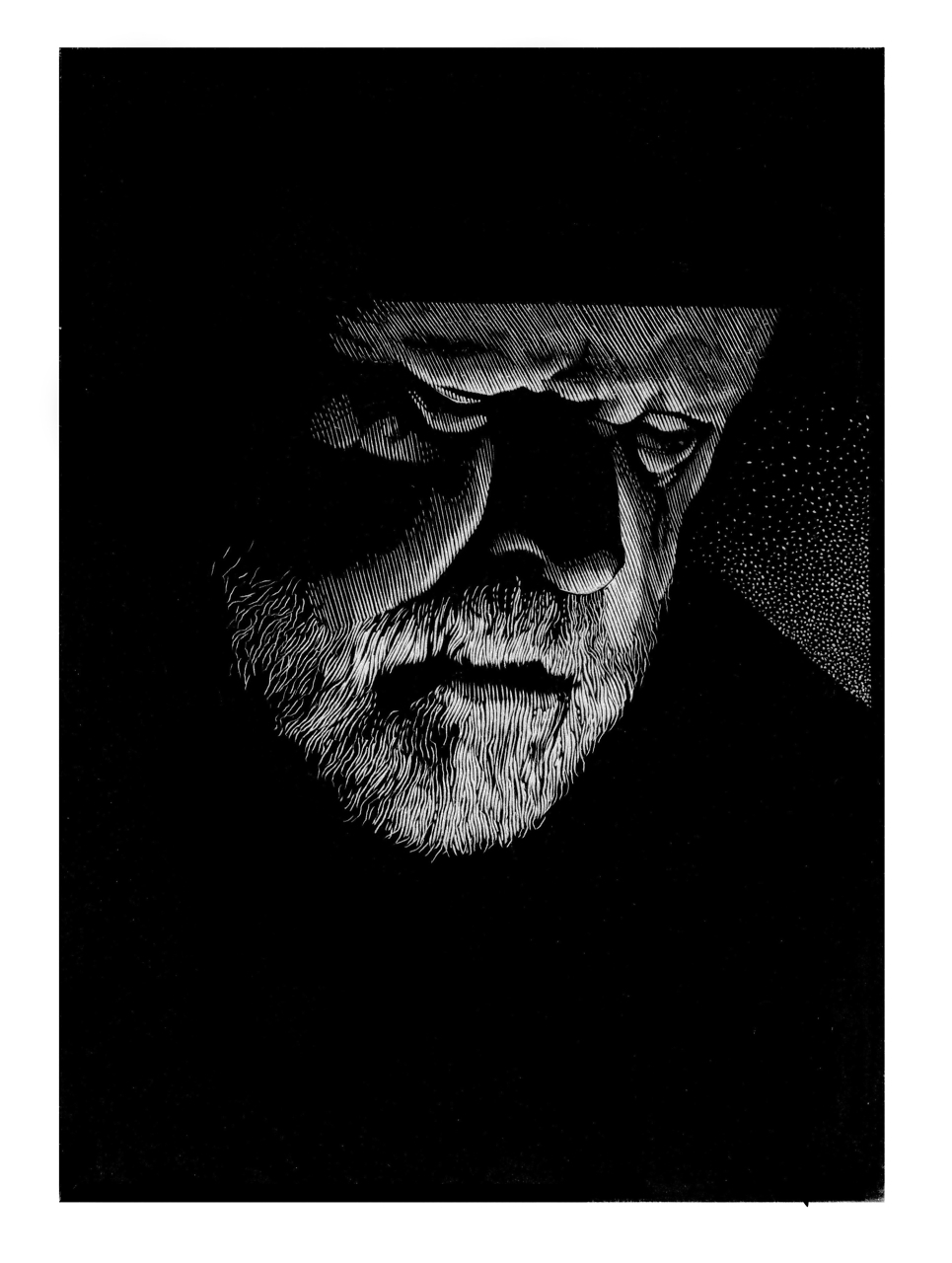

Iris Press issues two new posthumous books from poet and novelist George Scarbrough

George Scarbrough, who died in 2008, was a resonant and unique voice in American poetry throughout the last half of the twentieth century. In January 1941,very early in George’s career, Jesse Stuart wrote to him: “You are an Agrarian in practice. You are truly an Agrarian. You are not an Agrarian of ‘sweet theory,’ not one who talks it and doesn’t know anything about making a living from the soil. You are the true Agrarian who knows the earth, seedtime, growth and harvest. I hope you never lose this firm foundation.” Thirty-five years later, in 1976, Allen Tate read the manuscript for George’s New and Selected Poems and wrote: “In my opinion George Scarbrough is one of the few genuine poetic talents to appear in the South in the past generation. I hope that his work continues to get the attention it deserves.” Nearly three years after his death, George’s work continues to get attention, in fact, and his readership continues to grow. Two new books, out next month from Iris Press, will celebrate what would have been his ninety-sixth birthday.

George wrote virtually every day for over fifty years, and in the process he accumulated a very large body of work, much of it still unpublished. When I acquired Iris Press, all of his books currently in print were Iris titles, and I had the privilege of working with him, off and on, for the last twenty years of his productive life. During those years we discussed at length his plans for future publications, but realizing his strategy proved to be complicated and time-consuming. George has always needed a resourceful editor: he wrote on an antique manual typewriter with thoroughly used ribbons and on any paper that he was able to salvage. When he died, the work he left behind was not well organized, often redundant with handwritten corrections, and none of it was in digital form. Nevertheless, the plan is proceeding much as George had envisioned it.

George wrote virtually every day for over fifty years, and in the process he accumulated a very large body of work, much of it still unpublished. When I acquired Iris Press, all of his books currently in print were Iris titles, and I had the privilege of working with him, off and on, for the last twenty years of his productive life. During those years we discussed at length his plans for future publications, but realizing his strategy proved to be complicated and time-consuming. George has always needed a resourceful editor: he wrote on an antique manual typewriter with thoroughly used ribbons and on any paper that he was able to salvage. When he died, the work he left behind was not well organized, often redundant with handwritten corrections, and none of it was in digital form. Nevertheless, the plan is proceeding much as George had envisioned it.

In time, Iris will bring back into print most of George Scarbrough’s past collections; ultimately there will be several collections of new material and critical studies, as well. Next month, to that end, Iris will issue a carefully edited second edition of George’s novel, A Summer Ago (first published in 1986), and a new poetry collection, George’s sixth, called Under the Lemon Tree. In the years before his death, George had dreamed about seeing this book in print, but because of the great complexity of the project, it is only now ready for publication.

During the last ten years of his writing life George used an alter ego, writing in the voice of the legendary eighth-century Chinese poet, Han-shan. The most mysterious but least polished of the important Tang Dynasty poets, Han-shan is also the most resonant with many readers in the West. There are more than 300 surviving Han-shan poems, and there have been eight important English translations since Arthur Waley first translated twenty-seven of them in 1954. Gary Snyder is perhaps the best known of these translators and was probably responsible for Han-shan’s being so warmly embraced by the Beat-generation writers. Jack Kerouac dedicated his novel, The Dharma Bums, to Han-shan.

During the last ten years of his writing life George used an alter ego, writing in the voice of the legendary eighth-century Chinese poet, Han-shan. The most mysterious but least polished of the important Tang Dynasty poets, Han-shan is also the most resonant with many readers in the West. There are more than 300 surviving Han-shan poems, and there have been eight important English translations since Arthur Waley first translated twenty-seven of them in 1954. Gary Snyder is perhaps the best known of these translators and was probably responsible for Han-shan’s being so warmly embraced by the Beat-generation writers. Jack Kerouac dedicated his novel, The Dharma Bums, to Han-shan.

The poet’s real name is not known with certainty, and this was likely by design: he was probably a fugitive following the An Lu-shan rebellion of 755. Retreating to one of the most obscure locations in the empire, he led a reclusive life, always dreaming of reconciliation. His poems are simple, direct, and frank, never failing to call attention to the flaws in society as he sees them. He was a very good model for George Scarbrough, who felt rejected but sought the approval of his peers.

As soon as he was introduced to Han-shan in the early 1990s, through a 1962 translation by Burton Watson, George recognized a kindred spirit. Writing in the voice of Han-shan gave him the means to speak directly about the social abuses he saw around him but could not address so clearly in his own first-person voice. So he moved the Chinese recluse to the land between the Hiwassee and the Ocoee rivers in rural Polk County, Tennessee. Under the Lemon Tree includes 103 poems from the several hundred resulting from that translocation. The old sage has never seemed more at home.

At the Last Festival

By George Scarbrough

“All things happy and true

Happen under the lemon tree,”

Han-shan remembers saying

To the young prince on

An April day when order and

Arrangement ruled the garden

And gnomes were still in style.

“Poetry originated in gardens,”

He had said, “among exotic trees

And flowers and the mazes

Of topiary art. Music’s provenance

Had been among fountains, aided

And abetted by birdsong,

Wind chimes, and verbs that moved.”

The armature of any garden,

However, he believes is words,

And he had sought to charm the boy

With the mysteries of philology,

Missaying in order to say, he said.

But words failed him now

At the sight of ruined imperial

Arcades and belle tournures.

Around him hedges were untrimmed,

And once exotic flowers allowed to go

Wild in unkempt corners.

No yellow bird sang above

The brackish pool where golden carp

Once glinted in the sun.

The lemon tree was gone.

Through the open door of what

Had once been his beloved house,

Merchants cried:

“Come buy! Come buy!

Oranges fresh from the country!

Melons from a far province!”

Settling himself among cushions

Of silk and figured leather, studying

His manuscripts, Han-shan began the journey

Home as if he had never been away.

Copyright (c) 2011 by the estate of George Scarbrough. All rights reserved.