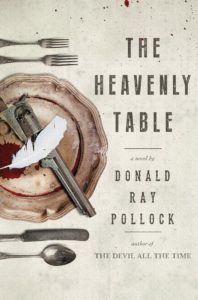

Every Man for Himself

Donald Ray Pollock’s The Heavenly Table, set in 1917, reveals desperate hardship among the rural poor

Pearl Jewett is a God-fearing man who lost his wife and farm and, with three sons in tow, is forced to wander the “harsh, impoverished South” looking for employment and sustenance. By the time he meets a hermit at Foggy River—in a region on the Georgia-Alabama border so desolate it seems abandoned by its Maker—Pearl has begun to doubt God’s existence, “for why would He treat some so badly and let others off the hook completely?” The hermit tells Pearl that he has it all wrong: suffering is a sign that God is preparing you for a glorious afterlife: “Without taking hold of some of the misery in the world, there can’t be no redemption.” Persevere through hardships, the hermit says, and “one day you’ll get to eat at the heavenly table.”

By that reckoning, the characters in Donald Ray Pollock’s The Heavenly Table endure sufficient suffering to warrant eternities of comfort and plenty, but after Pearl’s sudden death, the Jewett sons—Cane, Cob, and Chimney—bypass the experience of arduous acquiescence in favor of a life of crime. They kill a local landowner for his horses and begin to rob banks and shops as they venture north, dreaming of starting a new life in Canada.

Meanwhile, in southern Ohio, Ellsworth and Eula Fiddler are similarly destitute. After losing their entire savings to a swindler (and their son to debauchery), they are on the brink of ruin when they are offered a lifeline from a surprising source.

The paths of the Fiddlers and the newly christened “Jewett Gang” are fated to cross, but before they do Pollock takes time to illustrate the widespread misery endured by the rural poor. It’s the fall of 1917, and the Americans whose lives are now being exploited in ceaseless agrarian labor will soon be added to the grisly death toll in World War I. The general opinion among the heartland proletariat, most of whom cannot find Germany on a map, is that only a fool would fight a war for rich men quarrelling over dropped handkerchiefs. On the other hand, the Army’s promise to feed and house its soldiers represents a significant lifestyle improvement for at least the bottom quartile of the characters who roam this novel.

The Jewett Gang’s criminal career emits a whiff of class revenge. When millionaire playboy Reese Montgomery shoots at them from an airplane (a diversion from his usual hobbies of sponsoring death-fights and raping women), he is incensed when the Jewetts shoot back. “For Christ’s sake, he was a Montgomery,” he thinks, “his father played bridge with the Rockefellers, his mother had served as Grand Madam of the Heirloom Ball!”

Readers will cheer when young Montgomery takes a bullet through his neck, and even Montgomery’s father is privately grateful to the Jewetts for taking his wastrel son off his balance sheet. But, as his monied cohort reminds him, “you couldn’t let the hoi polloi think they could murder the privileged class without repercussions, or you’d end up with another Russia on your hands.”

Readers will cheer when young Montgomery takes a bullet through his neck, and even Montgomery’s father is privately grateful to the Jewetts for taking his wastrel son off his balance sheet. But, as his monied cohort reminds him, “you couldn’t let the hoi polloi think they could murder the privileged class without repercussions, or you’d end up with another Russia on your hands.”

As in his previous novel, The Devil All the Time (2011) and the story collection Knockemstiff (2008), Pollock populates The Heavenly Table with a colorful cast of roustabouts and degenerates. Young Eddie Fiddler makes a futile attempt to play harmonica in a house band for the “Whore Barn,” a trio of down-market prostitutes pimped by a seasoned hustler. Camp Pritchard, an Army base erected near the Fiddler place, is run by a lieutenant whose closeted homosexuality warps into luridly masochistic fantasies. Elsewhere the characters bump into a dissolute banjo player (is there any other kind?), an English teacher who drinks away his literary failures, an Army sergeant shell-shocked from serving in the Red Cross on the Western front, and a serial killer who keeps his victims’ teeth in a tin can so he can shake them like castanets.

What readers won’t find in Pollock’s novel are sustained portrayals of goodness. The Heavenly Table is not a novel for the faint of heart or the queasy of stomach. Pollock visits Biblical tortures on his characters and describes the underbelly of their lives in unsparing detail. No one simply gets killed in this novel; their chins get blown off, their heads smashed open, their stomachs eviscerated. Occasionally the graphic descriptions, reeled off with comic swiftness, feel almost misanthropic. But that very caprice gets to the bedrock of the book’s message. Pollock does not condemn the Jewetts for refusing to wait for divine benevolence; he celebrates them for realizing that, in this brief and perilous life, one must seize any opportunity to sample the weird and wonderful feast that the world has to offer.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.