Failure Club

The protagonist of Drew Perry’s new novel joins a long line of Southern losers

Southern writers don’t let their men off easily. Think of Barry Hannah, Larry Brown, and George Singleton, to name just a few: their protagonists are a thick crowd of failed or ridiculously flawed, if infuriatingly likeable, Southern men—men who are more often than not their own worst enemies, men who pilot pickups across modern Southern landscapes that look and feel nothing like the generous front porches and magnolia-scented breezes of Southern Lit as we once knew it.

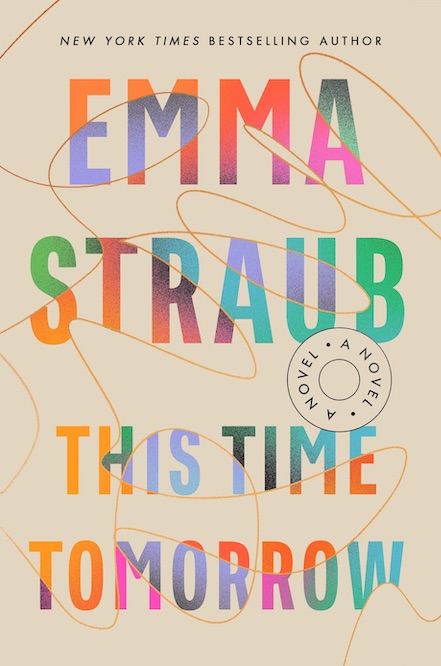

Enter Jack Lang, a modern Southern man whose life crisis is held up, often comically, for observation in This Is Just Exactly Like You, the debut novel from North Carolina writer Drew Perry. Jack is the perpetrator of many a stalled fix-it or build-it project, such as his kitchen, with its unfinished tile floor and busted-out wall. He wants to improve things, to tinker productively. But his best efforts tend to go awry, and his outsized impulse moves—like the purchase of the house identical to his, next door to his own, sold at auction—have driven his fed-up wife, Beth, an art history professor, to fly the coop. Her departure leaves Jack in charge of their six-year-old autistic son, Hendrick, who doesn’t speak except to repeat things he’s heard on TV or to rattle off items in a tree catalog. To add insult to Jack’s injury, Beth seeks refuge with his best friend, Canavan. Just about the only thing that is not a glorious mess in Jack’s life is his small business, Patriot Mulch & Tree, which is thriving, thanks to his right-hand man, Butner, a salty, agreeable guy—and perfect comic foil to Jack—who supplies the real horse sense and go-getter drive behind the company’s success.

In broad strokes, Jack is a strikingly recognizable figure, but—his similarities to the aforementioned failed Southern males notwithstanding—he’s also a type seldom seen in contemporary Southern lit. He’s not a redneck, nor is he an overeducated namby-pamby, though he worked for several years as an adjunct history professor at the same college where Beth teaches. For all his missteps, he’s not dumb or incompetent. He’s a regular guy who takes a carpe diem approach to life, along with a whopping dose of procrastination. (“Everybody wants him to plan,” Perry writes. “Often enough, here’s his plan: Not to.”)

In broad strokes, Jack is a strikingly recognizable figure, but—his similarities to the aforementioned failed Southern males notwithstanding—he’s also a type seldom seen in contemporary Southern lit. He’s not a redneck, nor is he an overeducated namby-pamby, though he worked for several years as an adjunct history professor at the same college where Beth teaches. For all his missteps, he’s not dumb or incompetent. He’s a regular guy who takes a carpe diem approach to life, along with a whopping dose of procrastination. (“Everybody wants him to plan,” Perry writes. “Often enough, here’s his plan: Not to.”)

Jack also belongs to that specimen of Southern man who can’t, or won’t, get in touch with his feelings except in grand and often destructive gestures—trenching Canavan’s yard, for example. The message: I feel, dammit. See? Just don’t make me talk or think too much about it. Nevertheless, his inability to access deep emotion is almost a fatal flaw for this novel, even as it drives the reader on: you know it’s in there somewhere, but Jack can’t bring it to light. As the novel progresses, this failure can make him an intensely frustrating character to follow. Because you really want to see him break through, you keep going, waiting anxiously for him to do so.

Along the way, Jack traverses the familiar, banal landscape in his old PM&T dump truck with its missing front fender and rusted doors and “air of authenticity.” Perry convincingly sketches that setting: auto lots with giant, inflatable, airbrushed animals on their roofs, and neighborhoods of double-wides where, “on the scalped land the houses look like growths, like something that might have to be taken off.”

Perry also does a nice job with Rena, Canavan’s estranged lover and Beth’s colleague (the two couples were good friends before the trouble began), who comes to Jack’s comfort and brings a welcome gust of spirit into the novel. No-nonsense, witty, and up for anything, Rena is, for Jack, “a creature from a completely different world.” She and Butner at times seem like two yipping, excitable dogs, circling around Jack, urging him to get off the porch and chase … something. “I feel like I’m dong everything wrong. I feel like I should feel—I don’t know … I feel like I should feel sadder,” he tells Rena. “Well, fuck, Jack, get sad!” she shoots back. “Be sad! That’s what this is for.” The friction is comic at times, but the reader, too, ultimately wants more from Jack—a little more edge, something more stirring beneath the surface.

Perry also does a nice job with Rena, Canavan’s estranged lover and Beth’s colleague (the two couples were good friends before the trouble began), who comes to Jack’s comfort and brings a welcome gust of spirit into the novel. No-nonsense, witty, and up for anything, Rena is, for Jack, “a creature from a completely different world.” She and Butner at times seem like two yipping, excitable dogs, circling around Jack, urging him to get off the porch and chase … something. “I feel like I’m dong everything wrong. I feel like I should feel—I don’t know … I feel like I should feel sadder,” he tells Rena. “Well, fuck, Jack, get sad!” she shoots back. “Be sad! That’s what this is for.” The friction is comic at times, but the reader, too, ultimately wants more from Jack—a little more edge, something more stirring beneath the surface.

That something is slow to come, so the novel can get sludgy in the last third. Hendrick’s autistic behavior is both a source of some light humor and pathos, although Perry comes up a bit short in making this young character augment the drama or complexity of the book. But in the final scenes, Jack acts on another impulse that brings levity to the proceedings and provides for some great, wacky visuals. It’s the perfect move for him to make: you want him to get real, to win back his wife—and what does he do as the pressure builds? That’s for the reader to find out, but in the end Jack Lang brings to mind another crew of Southern men so perfectly pinned in that great documentary film exploration of Southern masculinity, Sherman’s March: men who haul fiberglass rhinoceroses from place to place, looking for the right home, for some meaning to make or direction to take from it all.

Drew Perry signs This Is Exactly Like You at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Nashville on April 21 at 7 p.m.