Fantine's Folly

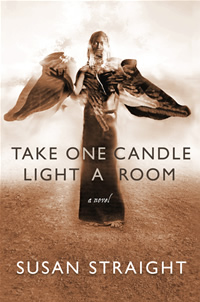

The protagonist of Susan Straight’s new novel can’t escape the past until she understands it

Traversing both the gentrified pockets and gangstaland of Los Angeles, as well as the sugar-cane fields and sweltering swampland of Louisiana, Susan Straight’s new novel is a complex work of art. Take One Candle Light a Room offers exquisitely rendered settings, lyrical prose, and a formidably large, multigenerational cast of characters. Its narrator, Fantine Antoine, an African American of Louisiana Creole descent and California birth, is an accomplished travel writer, but in this book she undertakes a journey unlike any she has experienced before—one that stands to alter her path permanently.

Fantine is the sole member of her family to leave the tiny, tight-knit community of Sarrat, nestled in the orange groves of Southern California. She has spent her adult years roaming the world on assignment, often alone and always under her pen name FX. Childless, and she has, in leaving her “tribe,” created a life that appears to be a rejection of everything that matters in the world she comes from. “People like us were not meant to measure success in the same way our families did. We were failures to them,” she reflects on herself and a fellow journalist friend. To Fantine’s mother, her absence is “almost as unforgivable as drug addiction or imprisonment.”

It is not lost on Fantine that the Sarrat community—founded in the late 1950s by her father, Enrique Antoine, originally of Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana—is just the sort of “remarkably unassimilated” cultural enclave over which her travel editors and readers would salivate. Enrique still speaks a clipped Creole patois (Straight’s evocation of the Louisiana Creole voice is brilliant and absorbing), and Fantine’s mother, Marie-Claire, makes an eye-watering gumbo every weekend.

It is not lost on Fantine that the Sarrat community—founded in the late 1950s by her father, Enrique Antoine, originally of Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana—is just the sort of “remarkably unassimilated” cultural enclave over which her travel editors and readers would salivate. Enrique still speaks a clipped Creole patois (Straight’s evocation of the Louisiana Creole voice is brilliant and absorbing), and Fantine’s mother, Marie-Claire, makes an eye-watering gumbo every weekend.

Taupe-skinned, her ethnicity indeterminate to strangers, Fantine has kept her heritage to herself, never revealing much to anyone. “Invisible,” she calls herself, and there is both pride and pain in her claiming of that word. Cool and self-possessed, she is practiced in steeling herself against any insults or taunts that might come her way, from her own community or the white world beyond it, and also against deep wells of loneliness and guilt for having strayed from her family. But as the book unfolds, her polished shell cracks.

The village of Sarrat was founded on a history of violence: five sixteen-year-old girls, including Fantine’s mother, left Louisiana to escape a white plantation owner named Mr. McQuine, who had raped several of them. His crime was only the latest in a long, bitter legacy of miscegenation and oppression—Fantine herself is descended from a slave who bore the children of white men. “It was my mother who told me the story,” she says, “so that I would stay home, safe, and never trust the outside world, or the white people in that world.” Fantine and three other girls are part of the new generation born to the five young women. They come of age together, as family. But as adults, the other women scoff at Fantine’s priorities, so alien to them. They scorn her absence, her worldly life among white people.

Virtually the only family member who doesn’t begrudge Fantine her career choice is her godson, Victor Picard, whose family is itself a study in violence. His father was murdered before Victor was born; his mother was Fantine’s closest childhood friend, Glorette. A crack addict and prostitute, she was murdered five years earlier. Shuttled from one low-rent apartment to another as a child, Victor has managed to transcend his troubled origins: he’s a community-college graduate, a lover of words. Fantine is a role model for Victor, but she has also been a fleeting presence, available only during brief visits between travels.

As the book opens, Fantine has arrived home from Switzerland in time to join her family in celebrating the memory of Glorette. She touches base with Victor, who is hanging out with his cousin Alfonso, recently released from a two-year prison sentence, and his friend Jazen, a notorious drug dealer in the nearby town of Rio Seco. They roam the streets in a Lincoln Navigator, and while Fantine knows Victor is not like the others, she’s also aware that he is not immune to the sinister pull of their world. When the boys are caught up in a homicide, she meets the news with a grim lack of surprise. Victor, she discerns from a few cryptic cell-phone exchanges, may have taken a bullet himself.

As the book opens, Fantine has arrived home from Switzerland in time to join her family in celebrating the memory of Glorette. She touches base with Victor, who is hanging out with his cousin Alfonso, recently released from a two-year prison sentence, and his friend Jazen, a notorious drug dealer in the nearby town of Rio Seco. They roam the streets in a Lincoln Navigator, and while Fantine knows Victor is not like the others, she’s also aware that he is not immune to the sinister pull of their world. When the boys are caught up in a homicide, she meets the news with a grim lack of surprise. Victor, she discerns from a few cryptic cell-phone exchanges, may have taken a bullet himself.

Thus begins Fantine’s quest to track down the boys and wrench Victor away from the company that will otherwise, she is certain, be his downfall. She sets off on a cross-country hunt with her father, trailing the boys as they make themselves scarce in the wake of the crime, bound for Louisiana where they have family.

As the narrative digs deep into the extended and connected families of Fantine’s and Victor’s ancestors, Fantine uncovers some of her own stoic father’s secrets—once again, violent acts color his history and haunt him still. The rural roads of Louisiana take Fantine deep into a place where the past is never dead, as the old Faulkner line goes, a place where women place salted meat on Victor’s wound, just as their ancestors did more than a century earlier. As Fantine pursues Victor, back in touch with family she hasn’t seen in decades, she feels shame and the weight of responsibility roiling inside her, and she is increasingly determined to make things right by her godson: “Victor had nothing. I’d given him nothing,” she thinks.

Meanwhile, another literal pressure looms: Hurricane Katrina has just grazed Florida and is bearing down on Louisiana. As Fantine and her father search for Victor—finding him in New Orleans, then losing him again—houses are boarded up as people leave in droves. This layering of the epic storm onto a narrative already taut with suspense may sound heavy-handed, but Straight executes the plot turn masterfully, spookily. The reader knows just what level of wrath is headed the characters’ way; the characters, of course, do not. And with every page, as Fantine prepares to ride out the storm with her father’s Aunt Monie, tension tightens around the reader like a vise.

Take One Candle Light a Room is not always an easy book, its tone frequently dark, its twists and turns and voices numerous, its sweep broad and historical despite a story that takes place over only a few days. But it is a book to be savored, to be read and re-read, slowly, thoughtfully, growing in impact and significance with each re-telling, like the stories of Fantine Antoine’s family.

Susan Straight will read from Take One Candle Light a Room at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Memphis on October 18 at 6 p.m.