Far From Home

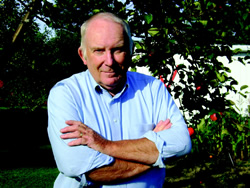

Howard Frank Mosher explains why he set his masterful Civil War novel in Tennessee

Howard Frank Mosher spent seven years researching and writing Walking to Gatlinburg, his tenth novel, set during the Civil War. The time and research show in the rich details, fully drawn characters, and well-crafted plot of the book, which follows seventeen-year-old Morgan Kinneson on a journey to find his brother, a missing Union doctor. Kinneson leaves his Vermont home and heads South to trace his brother’s steps. He is indeed walking to Gatlinburg, and the sometimes cruel, sometimes funny, and always fascinating people and situations he encounters along the way change him profoundly. Mosher answered questions from Chapter 16 via email just as the book was being released in paperback.

Chapter 16: The character names in the book are vivid and seem authentic. Do you collect names in your historical research?

Mosher: I do collect character names in my historical research. Two excellent sources for names, as well as all kinds of other period information, were John Rice Irwin’s incomparable Museum of Appalachia in Norris, Tennessee, and Horace Kephart’s great memoir, Our Southern Highlanders. But sometimes names that are simply too good not to use just pop up. When I saw a road sign for the Oconaluftee River, up in the Great Smokies, I had to have a character named Oconaluftee in Walking to Gatlinburg. (He’s a villain of nearly Elizabethan proportions.)

Chapter 16: In an interview on your website, you say that, at one point, the manuscript for the book was a thousand pages long. It’s tantalizing to think of the episodes that were omitted. How do you go about making such decisions, and is there any lost passage in particular that you can describe for us?

Mosher: A very great editor once told me, “Shorter is always better than longer.” In my early drafts, I’m apt to write dozens of scenes that don’t make the final cut. I hardly ever regret cutting anything, but I do miss one line of dialogue from a long-gone scene between the novel’s young Vermonter, Morgan, and General Grant. In a brief encounter in Chattanooga, Morgan asked Grant what he believed in. Grant responded by picking up a half-finished bottle of bourbon on his field desk and saying, “This. I believe in the very temporary power of this to make all of the madness bearable.” Ultimately, I decided that the scene slowed the story down too much and had to go.

Mosher: A very great editor once told me, “Shorter is always better than longer.” In my early drafts, I’m apt to write dozens of scenes that don’t make the final cut. I hardly ever regret cutting anything, but I do miss one line of dialogue from a long-gone scene between the novel’s young Vermonter, Morgan, and General Grant. In a brief encounter in Chattanooga, Morgan asked Grant what he believed in. Grant responded by picking up a half-finished bottle of bourbon on his field desk and saying, “This. I believe in the very temporary power of this to make all of the madness bearable.” Ultimately, I decided that the scene slowed the story down too much and had to go.

Chapter 16: Tennessee readers will naturally be curious about how you determined to set a portion of the novel in Gatlinburg. Had you visited the area, or did you while researching the book?

Mosher: Our daughter, Annie Mosher, is a singer/songwriter in Nashville. Over the course of the past ten years, in conjunction with visiting Annie and her family, I’ve fallen in love with the mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina. The theme park that is Gatlinburg today is a far, far cry from the handful of log cabins that made up the town in 1864. Mainly, though, I picked the name “Gatlinburg” for the title because of its musical sound and resonance. I can’t say just why, but I find it a beautiful name. And, of course, the Smoky Mountain National Park remains one of the most beautiful places in America or anywhere else.

Chapter 16 [SPOILER ALERT]: The death of Pilgrim felt utterly devastating. I wonder if, as the writer, you struggled with letting that character go. Did you have to think about it for a while, or did you know throughout that this would happen?

Mosher: Yes, it was very, very hard for me to have Pilgrim die. I did have to think long and hard about that decision. That’s what happened in the Civil War, though. More than half a million Americans died. On the southern leg of my book tour for Walking to Gatlinburg, someone asked me if I regarded it as an anti-war book. I said yes, I supposed so, but that after a certain point—Harper’s Ferry, maybe, or even the Missouri Compromise—the war was probably inevitable. More accurately, perhaps, Walking to Gatlinburg is an anti-violence book. One of the questions the novel raises is when, if ever, is violence morally justifiable. Pilgrim and his brother Morgan have very different takes on this question. I’m not sure how to answer it myself.

Mosher: Yes, it was very, very hard for me to have Pilgrim die. I did have to think long and hard about that decision. That’s what happened in the Civil War, though. More than half a million Americans died. On the southern leg of my book tour for Walking to Gatlinburg, someone asked me if I regarded it as an anti-war book. I said yes, I supposed so, but that after a certain point—Harper’s Ferry, maybe, or even the Missouri Compromise—the war was probably inevitable. More accurately, perhaps, Walking to Gatlinburg is an anti-violence book. One of the questions the novel raises is when, if ever, is violence morally justifiable. Pilgrim and his brother Morgan have very different takes on this question. I’m not sure how to answer it myself.

Chapter 16: In a starred review, Kirkus Reviews noted that Walking to Gatlinburg “cries out for a sequel.” Have you thought at all about writing a novel that tells Pilgrim’s story leading up to and during the war?

Mosher: I think that I’ve said about what I have to say when it comes to Pilgrim’s story. Interestingly, however, my 2007 novel, On Kingdom Mountain, tells the life story of Morgan’s very highly independent-minded daughter, Miss Jane Hubbell Kinneson, of Kingdom Mountain.

Chapter 16: On this journey, Morgan encounters the Melungeons, a people about whom stories are legend but relatively little is known. Is this sole otherworldly encounter in the novel a commentary on the elusive identity of the Melungeon people?

Mosher: I love the stories about the Melungeons. I first learned of them at the Museum of Appalachia. One theory is that the Melungeons of the remote hill country of eastern Tennessee are descendants of wrecked Portuguese sailors who made their way inland from the coast of North Carolina centuries ago. The Melungeon scene in the novel, however, is pure invention. It is, indeed, as you suggest, “a commentary on the elusive identity of the Melungeon people.” It’s also, in the grand old Howard Frank Mosher tradition, weird as all get-out!

Chapter 16: You wrote a memoir, called North Country, in which you traveled through the region of the country that is the setting for your fiction. That was in 1998, and you said then that you feared for the future of the region because of environmental damage and lack of opportunity, as jobs in farming and railroading, among other industries, disappeared. Do you feel the same today? Do you have any revived hope from relatively new phenomena like the growing interest in sustainable agricultures, CSAs, and organic produce and meats?

Mosher: Although I’ve written about the Civil War, the Lewis and Clark Expedition (The True Account) and major-league baseball (Waiting for Teddy Williams), most of my fiction is set in Vermont’s remote and mountainous Northeast Kingdom, which, in my fiction, I call Kingdom County. Situated at the far northern end of the same Appalachian range that stretches south to Tennessee and Georgia, it is an economically depressed region. For instance, fifty years ago, there were about 800 family farms in the county I live in. Today, there are fewer than eighty. There are, in fact, several local cheese-makers, furniture-makers, and organic meat and produce growers, but the economy is still sluggish and the “North Country” seems to serve as a kind of dumping ground for prisons, “waste management” areas, wind towers (providing electricity for elsewhere but not local homes and businesses) and second homes of the very wealthy. It’s telling that most local young people—including our son and daughter—who can leave the Northeast Kingdom after high school do so, and don’t return except to visit. Ironically, we here in the Kingdom have perhaps noticed the recent recession less than much of the rest of New England because this has always been a depressed area. Like much of Appalachia, it’s a great place to write about—a gold mine of wonderful stories—but a hard place to make a living in.

Chapter 16: What are you reading?

Mosher: I’m so glad that you asked this question. While not all readers are necessarily writers, all of the writers I know are avid readers. Recently, I wrote in my forthcoming memoir (The Great Northern Express: A Writer’s Journey Home, March 2012) that while I love to write, I live to read. By coincidence or otherwise, I’ve been reading a lot of great Southern writers lately. I just finished Tom Franklin’s new novel, Crooked Letter, Crooked Letter. (Is that a great title, or what!) Not long ago I reread William Gay‘s great story collection, I Hate to See That Evening Sun Go Down. Last week I finished Daniel Woodrell’s (Winter’s Bone), three early suspense novels, due out in April in one volume, The Bayou Trilogy. I’m reading, for the fourth or fifth time, Peter Taylor’s classic novel, A Summons to Memphis, one of the best, and saddest, family novels ever written in this country. And finally, I just finished the galleys of Steve Earle’s forthcoming novel, I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive. Only the man who wrote the great song “Copperhead Road” could have created this poignant, funny story of the ghost of the late, great Hank Williams, Senior, and the doctor who prescribed the drugs that probably killed old Hank. Many thanks to my Southern colleagues for continuing to make the American South the setting for much of the best literature coming out of these United States today. (I’ve often wondered if “Kingdom County” wouldn’t fit right into, say, east Tennessee, like a hand in a glove. But maybe that’s just wishful thinking—and even my resourceful Melungeon friends might find our seven-month winter somewhat of a challenge.)

To read Chapter 16‘s review of Walking to Gatlinburg, click here.