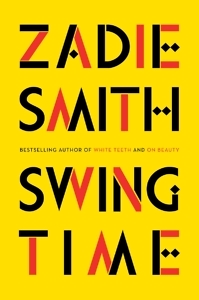

Fate of a Friendship

Zadie Smith’s Swing Time looks at female love and cruelty

Reading Zadie Smith’s fifth novel, Swing Time, is a little like first meeting an epic painting through one of its small, compelling details. The childhood friendship on which the novel rests is that detail—intimate, alive, seemingly complete in itself. But as the story progresses, Smith reveals a far larger canvas that grapples with themes of race, class, and gender, transcending the personal without ever losing sight of human passion embodied in the intense feelings between two little girls.

Swing Time’s unnamed narrator is a child of 1980s London, the daughter of a black, Jamaican-born mother and a white English father. A ballet class at a neighborhood church brings her into contact with Tracey, another child of mixed race whose “shade of brown was exactly the same—as if one piece of tan material had been cut to make us both.”

Both girls’ families live in public housing, but there the similarities end. The narrator’s mother is fiercely intellectual and ambitious, her father a doting plodder. Tracey’s mother is “white, obese, afflicted with acne,” and has a violent relationship with Tracey’s mostly absent black father. She makes her daughter a “striking accessory,” glamming the child up in jewelry and provocative clothes, while the narrator is obliged to follow her own mother’s more sober aesthetic and “admirable maternal restraint.”

The intense friendship that develops between the girls is complicated by a lurking, mutual envy. Tracey has superior beauty and talent, while the narrator possesses, though she’s barely aware of it, a happier life, with two loving, if imperfect, parents and none of Tracey’s gnawing need to prove her worth. The tension between them eventually ruins the friendship, but the pain of it continues to plague their adult lives, even as the narrator enters the glittery orbit of Aimee, a superstar pop singer. Through Aimee, her world expands to include the U.S. and West Africa, but everywhere she goes, she meets the same confounding realities of injustice she first knew in her London council estate, and she remains haunted by her confused feelings for Tracey.

Swing Time is a novel about women. The men in the book get their share of sympathy, but their feelings don’t carry much weight. Almost all the emotional power circulates between the women, who seem entirely necessary to each other in spite of the hurt they regularly inflict. They often want love or recognition they can’t get, and this desire sometimes morphs into an ineffective urge to rescue and lift up the sisterhood. Aimee—a very thinly disguised version of Madonna—wreaks havoc by making a vanity project out of a school for girls in West Africa. The narrator’s mother is determined not to see her daughter fall into the usual traps for young women, but her ideological feminism doesn’t offer much to address the real needs of the two girls right in front of her.

Swing Time is a novel about women. The men in the book get their share of sympathy, but their feelings don’t carry much weight. Almost all the emotional power circulates between the women, who seem entirely necessary to each other in spite of the hurt they regularly inflict. They often want love or recognition they can’t get, and this desire sometimes morphs into an ineffective urge to rescue and lift up the sisterhood. Aimee—a very thinly disguised version of Madonna—wreaks havoc by making a vanity project out of a school for girls in West Africa. The narrator’s mother is determined not to see her daughter fall into the usual traps for young women, but her ideological feminism doesn’t offer much to address the real needs of the two girls right in front of her.

The narrator feels for the plight of “this girl who lives everywhere and at all times in history, who is sweeping the yard or pouring out tea or carrying somebody else’s baby on her hip and looking over at you with a secret she can’t tell,” yet for all her sense of solidarity, she’s too wrapped up in trying to find her own way in the world to give much of herself to oppressed girls or anyone else.

One of the obstacles in finding her way is the inescapable issue of race. Her mixed heritage means the world can’t quite settle on a label for her, and her thoughtful temperament makes her disinclined toward anything resembling polemic. Yet she clearly understands, even as a young child, her status as Other. She has to hear her mother called “that bloody spade,” and later on she suffers the attentions of an overly friendly Iranian boss who mistakes her for Persian or Arab and then wants nothing to do with her when he learns the truth. When, while an aide to Aimee’s do-gooder foray into West Africa, she visits a site of the slave trade, she feels not so much horror as dispassionate identification: “The world is saturated in blood. Every tribe has their blood-soaked legacy. Here was mine.”

Swing Time weighs in at a hefty 450-plus pages, and there are times when the novel risks seeming a touch bloated. But the dry, slightly mocking voice of the narrator is always seductive, and Smith ultimately weaves the various threads of her narrative together into a web of disappointment, betrayal, and maternal longing that is somehow both heartbreaking and beautiful. The questions of race, sex, and class, so thoroughly explored throughout the book, become in the end simply an inextricable part of a deeply human story.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College, she has attended the Clothesline School of Writing in Chicago, the Moss Workshop with Richard Bausch at the University of Memphis, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. She lives in White Bluff.