Feeding Hearts and Minds

With National Library Week beginning on Sunday, a volunteer reflects on the stories she finds in the stacks

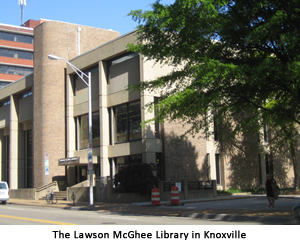

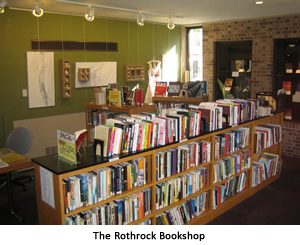

“My goodness,” says the woman at the counter. She has just pulled out two dollar bills and a quarter—the cost of two books and a magazine at Rothrock Bookshop, the used-book outlet at the Lawson-McGhee Public Library in Knoxville, where my friend Mary and I are working the midday shift. The woman, attractive and friendly, bends over her iPad, which she’s set on the counter. “My goodness,” she says again, flicking her index finger across its surface.

It’s a quiet, slow “my goodness,” something a person might say if she had found a ten-dollar bill in a new wallet she’d picked up to examine while browsing in a department store.

“Well, um, I’m not sure how this works—I just got the thing,” she says, more to herself than to us. Then she smiles. “It’s from my husband. We’re in counseling. He hasn’t spoken to me in three months, and now he’s sending me a text message.”

“Oh, my,” Mary and I say in unison.

“We went on a two-hour hike last weekend, and he didn’t say a word to me the whole time.” She’s still smiling as if she is not at all perturbed about this turn in her marriage, might even in fact be enjoying a change of habit. “Actually,” she adds, “it’s been great for my reading.”

“Well, gosh, good luck and good reading,” I say as she thanks us and leaves along with a group of young mothers and toddlers drifting up from the Children’s Library downstairs. Baby Bookworms must be over. A young man and two cute preschoolers, both girls wearing flowery dresses and tights striped in pink, orange, and lime green, wander in and head for our children’s shelves. From their chatter, I can tell the girls are just beginning to realize what a really big adventure reading is.

For a book lover, working in the downtown library’s used-book shop, surrounded by books and other book lovers, is the ultimate volunteer gig. The thousands of used books, magazines, and videos sold in Rothrock and at the library’s annual used-book sale are under the sole management of Friends of the Library, about a hundred of whom are volunteers. Our efforts add thousands of much-needed dollars to the library’s annual operating budget. Working here is always fun, and not just because of the books but also because of the people who drop in, because of the snippets of stories they tease us with. As a writer, I find it as rich as a candy store.

For a book lover, working in the downtown library’s used-book shop, surrounded by books and other book lovers, is the ultimate volunteer gig. The thousands of used books, magazines, and videos sold in Rothrock and at the library’s annual used-book sale are under the sole management of Friends of the Library, about a hundred of whom are volunteers. Our efforts add thousands of much-needed dollars to the library’s annual operating budget. Working here is always fun, and not just because of the books but also because of the people who drop in, because of the snippets of stories they tease us with. As a writer, I find it as rich as a candy store.

The sorting crew has just brought up from the basement a cart loaded with two- and three-year-old magazines, the glossy kind that take a long time to feel dated and are a bargain at twenty-five cents each: The New Yorker, Opera Now, Outside, Organic Gardening. Two women come in—regulars, heavy readers. They work in a bank, always lunch together, and once a week stop in the bookshop. One of them pages through a Bon Appétit.

“I could never take this magazine,” she says. “I would have to cook. It would keep me from doing other important things…like daydreaming.” We all laugh—modern, middle-class women who cook only for aesthetic reasons and not out of necessity, as our mothers did.

Mary leans toward me, nodding toward the window. “He’s talking to himself,” she says, her voice so low I can barely understand her. I look at the man outside who is, yes, in deep conversation with himself. He’s short, thin, with cropped white hair. He could be any age from fifty to seventy. His clothes are wrinkled, his white socks pulled up over the bottoms of his pant legs, his sneakers filthy. He’s standing still, but his head turns left and right, his mouth moving nonstop.

“Yes, well, that’s not unusual,” I say, going back to making space for the magazines. I live downtown and am accustomed to the homeless. They like to hang out at the library. It’s one of few truly democratic public spaces where they feel comfortable, maybe almost equal. Mary lives in the suburbs, where no one is homeless.

Soon it’s three o’clock, the end of our shift. Nan, our replacement, arrives. She’ll be working until 6:30 alone. As Mary and I gather up our things and head for the door, the white-haired man comes in. We hesitate for a minute to hear what he is saying to Nan.

“I want you to find me some books I’d like to read,” he says. “Can you just do that for me? Just find me some books I’d like.” Nan looks at him as one might look at someone who is speaking a foreign language. Finally, as he starts repeating himself, she interrupts. “Okay, but first I need to know what kind of books you like to read.” It’s as if he hasn’t heard her, just continues like a needle stuck on a turntable, “I want you to find me some books I’d like. Can you just do that for me? I want you to find me some books I’d like to read. Can you just do that?”

“I want you to find me some books I’d like to read,” he says. “Can you just do that for me? Just find me some books I’d like.” Nan looks at him as one might look at someone who is speaking a foreign language. Finally, as he starts repeating himself, she interrupts. “Okay, but first I need to know what kind of books you like to read.” It’s as if he hasn’t heard her, just continues like a needle stuck on a turntable, “I want you to find me some books I’d like. Can you just do that for me? I want you to find me some books I’d like to read. Can you just do that?”

He isn’t agitated or bullying; on the contrary, he is as calm and confident as a CEO exercising his authority over a staff member. More than that, he has the natural audacity of someone who is pleased with his performance. Mary and I look at each other with sad smiles; we are slow in pushing the door to the outside. Mary is probably thinking we ought to ask the security guard to keep an eye on the situation. I’m thinking, I wonder what his story is?

We part ways, Mary to the parking garage, I to my condo a block away. I carry two magazines and a couple of DVDs recommended by Heather, my go-to librarian for foreign films. One of the magazines is an issue of The New Yorker I bought for an article by Judith Thurman on Amelia Earhart. Thurman seems to me a genius, able to write brilliantly on any subject. You can find lots about her writing on the Internet but nothing about her personally. And that makes sense since I suspect she’s really a robot The New Yorker hides in its basement, a little voracious machine that chews through digitized libraries all day and spits out stellar monographs all night. The other magazine is a copy of Bon Appétit that I bought just for the pictures, for the daydreaming.

The sky is overcast, the air sweetened by a type of English laurel that’s planted all over downtown. I wonder if the woman with the silent husband will bring her book to the dinner table this evening. I wonder what the homeless man will be eating. How lucky, I think, to live in a world where public libraries, a concept that possibly began in the seventh century with a collection of thousands of clay tablets by an Assyrian king in the city of Ninevah, still feed, for free, the hearts and minds of so many.

Copyright (c) 2012 by Judy Loest. All rights reserved. Judy Loest is a freelance writer living in Knoxville