“Fiction Was My First Love”

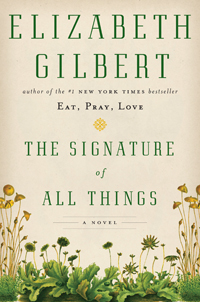

Elizabeth Gilbert talks with Chapter 16 about her new historical novel, The Signature of All Things

Elizabeth Gilbert’s 2006 memoir, Eat, Pray, Love, recounted the now-famous story of how the newly divorced author, at age thirty-one, left her home in New York to spend four months each in Italy, India, and Indonesia. The book became a bestselling favorite of book clubs, and Gilbert herself was played by Julia Roberts in the blockbuster film—and those two facts combined to provide a quick ticket to writerly super-stardom. Elizabeth Gilbert became one of the most famous memoirist of a memoir-dense literary era.

Less well known is that fact that Gilbert actually wrote much of Eat, Pray, Love while serving as a visiting writer at the University of Tennessee during the spring semester of 2005. Gilbert, says Knoxville author Michael Knight, “was one of the most dynamic and popular visiting writers we’ve had at U.T. Her buoyant intellect and sprit were downright contagious. Her students loved her. She kept in touch with some of them for years after she left Knoxville.” Knight added, “Of course nobody knew what was about to happen with Eat, Pray, Love, or that Gilbert was about to explode in the literary world, but the same qualities that made her a good teacher are readily apparent in her prose, no matter what she’s writing about – that vibrancy, that intellect. There’s life in her, you know, and it comes through in person and on the page.”

Less well known is that fact that Gilbert actually wrote much of Eat, Pray, Love while serving as a visiting writer at the University of Tennessee during the spring semester of 2005. Gilbert, says Knoxville author Michael Knight, “was one of the most dynamic and popular visiting writers we’ve had at U.T. Her buoyant intellect and sprit were downright contagious. Her students loved her. She kept in touch with some of them for years after she left Knoxville.” Knight added, “Of course nobody knew what was about to happen with Eat, Pray, Love, or that Gilbert was about to explode in the literary world, but the same qualities that made her a good teacher are readily apparent in her prose, no matter what she’s writing about – that vibrancy, that intellect. There’s life in her, you know, and it comes through in person and on the page.”

The Signature of All Things marks Gilbert’s return to fiction for the first time in more than a decade. An expansive historical novel, the book follows a well-to-do Philadelphia woman, Alma Whittaker, born in 1800 to an entrepreneurial father and a strict Dutch mother. Before settling down, Alma’s father had traveled with Captain James Cook, and his adventurous tales take root in Alma. Her hunger for learning leads first to an encyclopedic knowledge of plants, flora, and the natural world, and then to startling, fantastic discoveries in far-flung places like Tahiti. This saga of discovery, romance, self-reliance, rebellion, and wit is of a piece with Gilbert’s earlier work, both true and imagined.

In advance of her upcoming appearances in Nashville and Knoxville, Gilbert answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: In E. Annie Proulx’s short story “Bedrock,” the main character feels “loosened from his life.” I’m wondering if you might’ve felt much the same way after the release of Eat, Pray, Love.

Elizabeth Gilbert: Oh, I have a habit of getting loosened from and then refastened to my life in pretty regular cycles. It is not entirely unpleasant to get loosened from your life every once in a while. The view changes. Your assumptions change. Loosening from your life (voluntarily or accidentally) is how you transform, and transformation is the only way we can be sure we aren’t dead yet. So, yes, I would say that I was unloosened, in a bunch of ways, and I would say that I rather appreciated it in the end.

Chapter 16: What compelled you to return to fiction after a thirteen-year absence?

Gilbert: I missed it. Fiction was my first love and always my intended life’s work. That said, if you are lucky enough to have a skill, I think you can use it in any way you like or need—and for a big chunk of time there I needed to use my writing to help me sort out some stuff about the real world. But once I got myself organized and settled again (or as much as possible), I decided to use my writing to return to my first love again— to the imagined world.

Chapter 16: The scope of The Signature of All Things is exhaustive, leaving no stone (or moss) unturned. How did you undertake the requisite research, from scientific to historical? Where did you begin?

Gilbert: I began by doing an overview of study for several months on the basic history of nineteenth-century botany, just to wrap my mind around it. Then I narrowed in on the parts that felt right for my plot—medicinal plants, taxonomy, women’s contributions to botanical science, the evolution debate, the role of missionaries in botanical commerce, the role of the Dutch, the beginnings of the pharmaceutical trade, etc. Then I read for three years, until my eyes turned to custard. I also spoke with botanical historians and moss experts and traveled from London to Amsterdam to French Polynesia to be sure I got the settings right. But all of this for me is pleasure—the highest pleasure. There’s nothing I love more than nerding out, and this book really allowed me to nerd out to the most extreme degree.

Gilbert: I began by doing an overview of study for several months on the basic history of nineteenth-century botany, just to wrap my mind around it. Then I narrowed in on the parts that felt right for my plot—medicinal plants, taxonomy, women’s contributions to botanical science, the evolution debate, the role of missionaries in botanical commerce, the role of the Dutch, the beginnings of the pharmaceutical trade, etc. Then I read for three years, until my eyes turned to custard. I also spoke with botanical historians and moss experts and traveled from London to Amsterdam to French Polynesia to be sure I got the settings right. But all of this for me is pleasure—the highest pleasure. There’s nothing I love more than nerding out, and this book really allowed me to nerd out to the most extreme degree.

Chapter 16: Can you explain the magic of bryology? Why, specifically, did you focus on mosses?

Gilbert: Mosses are enormous, complex, and ancient—in fact, the oldest land plants on earth and some of the most diverse. A person studying mosses is really studying time, which is what could have feasibly led Alma into questions of evolution and transmutation. Also, because mosses are so tiny and intricate, they reminded me of the sort of work that women have always done—needlework, especially, which is also time-consuming and miniaturized, and traditionally a way for women to express their creativity without taking up too much space or using too many resources. It felt appropriate that a woman would study something so fine.

Chapter 16: In her adventuring, Alma reminds me a little of Eustace Conway, the iconoclastic subject of your 2002 nonfiction book, The Last American Man: “The American boy came of age by leaving civilization and striking out toward the hills,” you wrote. And in a way, of course, you yourself left civilization behind, too, in Eat, Pray, Love. Is there a particular aspect of chucking it all that you find most interesting to explore in a book?

Gilbert: To put it simply, there’s an old adage that says, “There are only two stories that have ever been told: either you go on a trip, or a stranger comes to town.” What kind of writer you are is largely determined by which of these two stories you find more compelling. I’ve always been a “you go on a trip” kind of soul, and I like best those sorts of adventures where somebody (whether myself or another person) chucks it all away and goes wandering. I chalk this up to never having wanted to be the person who waits around for the stranger who comes to town; I wanted to be the stranger who comes to town.

Chapter 16: Why is it vital to this story that Alma be a woman instead of a man?

Gilbert: Because women are traditionally underfoot and overlooked, not unlike mosses. As such, there are more hidden mysteries to unfold. It’s a far more interesting and surprising story, a woman’s life.

Elizabeth Gilbert will discuss The Signature of All Things at the Nashville Public Library on November 1, 2013, at 6:15 p.m. as part of the Salon@615 series. She will also appear at the Tennessee Theatre in Knoxville on November 2, 2013, at 7 p.m. The Nashville event is free. Tickets for the Knoxville event are $35 and include a copy of the novel.