Fighting Against War

Lawrence Wright takes readers behind the rancorous scenes of the Camp David Accords

By 1978, halfway through what Jimmy Carter hoped would be only his first term as president, the nation was growing weary with him. The U.S. economy dragged, the president’s relationship with Congress was chilly, and he offered no cure for the “malaise” that plagued Americans. Carter needed a spectacular win to demonstrate his relevance, and he had long dreamed of bringing peace to the Middle East. His opportunity came from an unexpected quarter—Egypt. President Anwar Sadat was suddenly making overtures to Israel; after four wars in thirty years, Egypt had had enough.

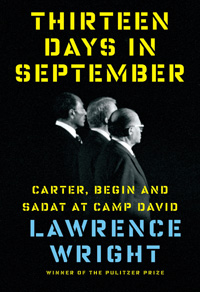

Carter seized the opportunity for a foreign-policy success and, in one of the highest-stakes diplomatic moves ever made by a U.S. president, brought Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin to the presidential retreat in the mountains of Maryland to see if an agreement could be reached. In Thirteen Days in September: Carter, Begin, and Sadat at Camp David, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Lawrence Wright details the behind-the-scenes action, where personalities mattered more than facts, and the religious traditions of three great faiths that propelled the participants through an elaborate, cliffhanging dance.

Carter seized the opportunity for a foreign-policy success and, in one of the highest-stakes diplomatic moves ever made by a U.S. president, brought Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin to the presidential retreat in the mountains of Maryland to see if an agreement could be reached. In Thirteen Days in September: Carter, Begin, and Sadat at Camp David, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Lawrence Wright details the behind-the-scenes action, where personalities mattered more than facts, and the religious traditions of three great faiths that propelled the participants through an elaborate, cliffhanging dance.

A devout Christian, Jimmy Carter knew his Bible forward and backward; he also had a clear understanding of the history of the Middle East. Carter, according to Wright, “had come to believe that God wanted him to bring peace, and that somehow he would find a way to do so.” It required zealous conviction even to try. By the mid-1970s, several American presidents had seen their peacemaking efforts rebuffed by the intransigence of the Arabs and Israelis. Even Nixon and Kissinger, who had opened relations with China and concluded peace with the North Vietnamese, made little headway in the diplomatic quicksand of the Holy Land. But Carter felt a calling to try and started looking for possible partners in the region as soon as he moved into the White House.

Anwar Sadat had been a terrorist in the 1940s, fighting British rule in Egypt. As a military officer and politician he was bold, unpredictable, and often difficult. In 1977, in a move that caught everyone in the world by surprise, he flew to Israel and spoke to the Israeli parliament about his desire to put the wars behind them. The Egyptian president’s terms were completely unacceptable to Jewish leaders, but Sadat’s opening gambit put pressure on the Israelis to reciprocate. Carter upped the pressure and convinced Begin to visit Camp David for a three-day summit to see if a framework for peace could be achieved. Begin, also a former terrorist who had fought British rule in Palestine, reluctantly agreed. Three days turned to thirteen, an eternity in politics. The press was kept in the dark, the negotiating teams were virtual prisoners, and the world held its collective breath.

Wright, who began his writing career in Nashville at the Race Relations Reporter, masterfully tells the story day-by-day, relating the intimate details of the meetings, discussions, and outright shouting matches that took place in that secluded mountain paradise. Throughout the story he weaves in important context, including a history of the conflict and fascinating mini-biographies of the principal participants. Wright’s experience as a playwright—his play about the negotiations is called Camp David—serves him well in setting the scenes and describing the human interactions that defined the struggle for an agreement.

Wright, who began his writing career in Nashville at the Race Relations Reporter, masterfully tells the story day-by-day, relating the intimate details of the meetings, discussions, and outright shouting matches that took place in that secluded mountain paradise. Throughout the story he weaves in important context, including a history of the conflict and fascinating mini-biographies of the principal participants. Wright’s experience as a playwright—his play about the negotiations is called Camp David—serves him well in setting the scenes and describing the human interactions that defined the struggle for an agreement.

And a struggle it was. As Wright points out, “Hatred is so much easier than reconciliation; no sacrifices or compromises are required. War holds out the promise of victory, and with it the enticing prospect of redemption from the humiliation of the past.” Carter had to push hard against this allure, sometimes losing his temper at the stubbornness of his fellow heads of state and even, in one extreme instance, physically blocking their exit from a room until they agreed to talk further.

At the end of the thirteen days, Carter triumphantly announced not one but two agreements. One accord outlined peace between Egypt and Israel, the first such deal between an Arab nation and the Jewish state. The second proposed a framework for resolution of the larger Palestinian conflict. Ultimately, as Wright notes, the accords were only partially successful and introduced additional problems. Sadat was assassinated because he had made peace with an enemy, Carter lost reelection in part because of subsequent political upheaval in the Middle East, and Begin firmly resisted any settlement to the Palestinian problem, dooming the second accord to the trash heap of good intentions.

But despite these failures, the signing of the Camp David Accords is still hailed as one of the great diplomatic achievements of all time. America’s reputation as a world leader rose as a result of those days of grueling effort, and the negotiating tactics that were employed there—most cobbled together on the fly during the talks—are now considered models of the diplomat’s art.

Finally, and most importantly, Israel and Egypt remain at peace more than three and a half decades after Camp David. The two nations have not resumed shooting at each other despite repeated temptation to avenge old wounds. Together they serve as a stubborn reminder of what may yet be possible, if only leaders of conviction and courage would act.

A Michigan native, Chris Scott is an unrepentant Yankee who arrived in Nashville more than twenty years ago and has gradually adapted to Southern ways. He is a geologist by profession and an historian by avocation.