For Opening Day

A Chapter 16 writer meditates on the mysterious power of baseball

Through the haze of forty years, I remember a man named Fred Norton. Baseball player. This was in Knoxville, Tennessee, in the 1970s, back when I was still practicing law.

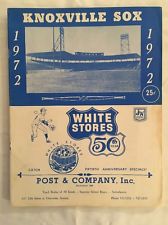

Knoxville had a AA baseball team in those days (two steps removed from the magic of the big leagues) operated at a financial loss by a generous man who owned a local laundry. The games were played before a brooding iron grandstand named for a Knoxville native, Bill Meyer, who had an indifferent four-decade career in the game. It sat between a vacant lot and a train track in a bad part of town, with an outfield fence made of wooden placards advertising local businesses, some defunct and forgotten. The PA system was barely audible, and the weak lighting gave the field a dim, dusty glow.

The Knoxville team was a AA affiliate of the Chicago White Sox, so of course it was called the “Knox Sox.” Its games drew scarcely any fans. There were usually fewer than 100 people on hand, and many of those who came seemed lost, like troubled souls stumbling into an empty church, or, like me, simply sitting in the silence, absorbed in the mysteries of the game.

The Knoxville team was a AA affiliate of the Chicago White Sox, so of course it was called the “Knox Sox.” Its games drew scarcely any fans. There were usually fewer than 100 people on hand, and many of those who came seemed lost, like troubled souls stumbling into an empty church, or, like me, simply sitting in the silence, absorbed in the mysteries of the game.

Every night, Fred Norton played centerfield for the Sox.

Fred was a tall man, and spare, but as lean and muscled as a greyhound. A pure athlete. In the outfield he ran with explosive grace, unerringly to the ball. His arm was not powerful, but his outfield throws always hit the cut-off man and never went to the wrong base. As a batter, he was a basic slap-hitter—a banjo hitter, they called them—going with the pitch to the opposite field and rarely trying to pull for power. I don’t think I ever saw him hit a homerun, though a deep sacrifice fly was within his capacity when the occasion demanded. He could bunt and he was good at moving runners over, and he could steal a base now and then.

In short, he was a fine baseball player, but with few prospects beyond AA ball.

He stood apart from most of his teammates. He was older than many of the young Sox who were beginning their innocent and excited voyages through the minor leagues, and he knew the looming heartbreak the game held in store for them. He kept to himself during the pre-game jostling and joking, doing his stretches and running silently, eyes fixed in the grass or in the darkening skies of the summer evening. He had a sense about him of ascetic dedication to his craft. He prepared for each game as a priest might prepare for mass.

He was an outstanding outfielder, running down drives in the farthest reaches of the park and coming in at ballistic speed for sinking liners. Standing alone in the dim light of centerfield between pitches, he faded into an apparition and passed into near invisibility, springing into view only when he burst into motion. When a ball was crushed deep into the outfield, he would turn his back and sprint into the vague shadows of deep center as though he were disappearing off the edge of the earth, into an apotheosis. Then, after another beautiful catch, he would return to the dugout with his eyes to the ground, expressionless, but pounding his glove in quiet satisfaction.

He was an outstanding outfielder, running down drives in the farthest reaches of the park and coming in at ballistic speed for sinking liners. Standing alone in the dim light of centerfield between pitches, he faded into an apparition and passed into near invisibility, springing into view only when he burst into motion. When a ball was crushed deep into the outfield, he would turn his back and sprint into the vague shadows of deep center as though he were disappearing off the edge of the earth, into an apotheosis. Then, after another beautiful catch, he would return to the dugout with his eyes to the ground, expressionless, but pounding his glove in quiet satisfaction.

I encountered Fred after a game one night on the darkened runway behind the stadium, and I spoke to him, offering him some kind of compliment on his night’s play. He looked up at me quickly with what I can only describe as fear in his eyes and hurried on without reply.

Norton seemed like a man possessed by baseball, enchanted by the game, playing compulsively as if driven, not by choice but by an inner spring released in him many years before, a power that pushed him to play long past the time he surely knew he would never make it out of AA.

And so it enchants me too.

Copyright (c) 2017 by Wayne Christeson. All rights reserved. Chapter 16‘s copyeditor, Wayne Christeson, is a Vanderbilt graduate and a retired attorney who has lived on a farm in Leiper’s Fork, Tennessee, for twenty-five years. His work has appeared in Vanderbilt Magazine, Nashville Arts, the Nashville Scene, and the Lost Coast Review, among other publications.