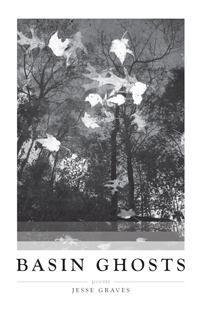

Going into the Shadows

Poet Jesse Graves gracefully explores difficult territory in Basin Ghosts

In “The Invitations,” the opening poem in Jesse Graves’s new collection, Basin Ghosts, wild voices beckon the child the poet once was: “Step from behind that porch bannister— / You have nothing but friends in the woods.” The child follows the voices, abandoning “human homes” and becoming one with the untamed world. It’s an image that conveys the powerful pull of nature on the human psyche, but it’s also a metaphor for an artist’s initiation into the creative life, the life of empathy and vision beyond the self. Though the poems in this collection are focused directly on Graves’s own store of memories and experiences, their real concerns are philosophical, even mystical—the work of that child venturing into the shadowy wood.

Graves seems fascinated by the ways that vision, both literal and imaginative, can shift and create the world. In both “Two Sunrises” and “Two Sunsets,” he simply changes focus from far to near, contrasting the grand vistas in the distance with the gritty and lovely realities up close: for Graves, what we see is what the world becomes. “Goldengrove” follows the poet and his daughter into a field where the bones of a dead cow are scattered, prompting a creative vision. “The girl’s eyes announce” that something must be done, and so the two of them “build a drumlin of bones,” which they imagine as “Halcyon home to the wind, / Or shelter for any wayward bird.” In “Nocturne,” the poet and his wife walk out into the darkness of a chilly evening, hoping to enjoy the quiet, but they turn to look back at the glow of a lamp in their child’s bedroom window. The sight transports the sleeping child into the couple’s moment of shared solitude: “Her breathing feels so near, / above the low whistle of moisture / shaken from leaves, I can almost hear it.”

Graves seems fascinated by the ways that vision, both literal and imaginative, can shift and create the world. In both “Two Sunrises” and “Two Sunsets,” he simply changes focus from far to near, contrasting the grand vistas in the distance with the gritty and lovely realities up close: for Graves, what we see is what the world becomes. “Goldengrove” follows the poet and his daughter into a field where the bones of a dead cow are scattered, prompting a creative vision. “The girl’s eyes announce” that something must be done, and so the two of them “build a drumlin of bones,” which they imagine as “Halcyon home to the wind, / Or shelter for any wayward bird.” In “Nocturne,” the poet and his wife walk out into the darkness of a chilly evening, hoping to enjoy the quiet, but they turn to look back at the glow of a lamp in their child’s bedroom window. The sight transports the sleeping child into the couple’s moment of shared solitude: “Her breathing feels so near, / above the low whistle of moisture / shaken from leaves, I can almost hear it.”

Questions of envisioning also come into play in the poems that mine the past. “Try to see the house as though you didn’t / grow up there” the poet writes of his childhood home in “Source,” as he attempts to reconcile the child he was with the man he has become. In “Dream Life,” a dead uncle returns in dreams, taking new forms each time until his image fades into “the way leaves in mid-October look / when you try to remember them in January.”

Death, of course, is a principal subject in Basin Ghosts, and while there is grief here, Graves often speaks not so much of pain as of wonder and puzzlement at the finality of loss. “My brother, how far apart are we tonight?” he asks in “Veil,” one of several poems about his dead brother. It’s a question with no answer, and Graves finds himself falling back on prayer, a “language I thought long forgotten.” “Ruble Johnson” is the story of a death foreseen, but it becomes a meditation on death as our shared fate, as Graves reflects on how the tale has outlived a generation of tellers.

Death, of course, is a principal subject in Basin Ghosts, and while there is grief here, Graves often speaks not so much of pain as of wonder and puzzlement at the finality of loss. “My brother, how far apart are we tonight?” he asks in “Veil,” one of several poems about his dead brother. It’s a question with no answer, and Graves finds himself falling back on prayer, a “language I thought long forgotten.” “Ruble Johnson” is the story of a death foreseen, but it becomes a meditation on death as our shared fate, as Graves reflects on how the tale has outlived a generation of tellers.

A death inspired one of the finest poems in the collection, “Pretty Music.” Its three stanzas travel from loss to love to the great cycle of life via nothing more than a handful of precise, concrete images. The first-person narrative begins with the simply stated fact of a woman’s death—“My aunt June lies buried on a hillside / between a hayfield and a briar thicket”—and the time since her passing is noted exactly as “a year and eight days” or, in nature’s measurement, long enough for the “skiffs of snow” to fall and melt away. The next stanza is a memory of June in life, holding a pail of blackberries and listening to her nephew play the guitar. It’s one of those moments when life is exalted by a small pleasure; for June, it’s one of her last such moments: “Absorbed in the changing light, by the heat / of one final summer, she leaned in to listen.” The final stanza returns to the present, with the narrator abandoning his guitar for the songs of nature and the graveyard:

rain pellets whistling off carved granite,

the high pitch of rye grass in springtime

rising up through the oblivious soil.

It’s a deceptively simple poem—just eighteen lines of seamless reflection that go directly to the heart of the world, to the ineluctable truths of time and existence. The rhythm of the lines is subtle but carries us irresistibly into the poem, as surely as the forest voices lured the child in “The Invitations.”

All the poems in Basin Ghosts are short and written in plain language, but many of them have a sort of camouflaged complexity that is revealed only on reflection. There is abundant love and tender memory here, but Graves is also working some of the most difficult territory of life, often within a single poem. He goes gracefully into the shadows.

[To read “Pretty Music,” click here.]

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College, she has attended the Clothesline School of Writing in Chicago, the Moss Workshop with Richard Bausch at the University of Memphis, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. She lives in White Bluff.