Good Medicine

A Chapter 16 contributor returns to the Sewanee Writers’ Conference

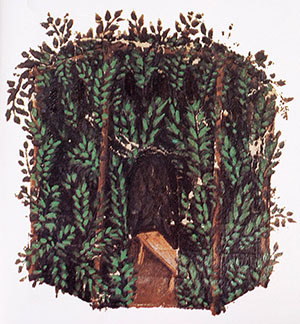

Two summers ago, when I learned I’d been accepted to the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, I wasn’t sure how to react. By the time I received the news, I was weeks into a debilitating illness that had left me unable to walk and unsure how much mobility I’d ever regain. I was in constant pain, barely able to stand up on crutches. My friends and family tried to look supportive when I insisted that I would be well enough to go to Sewanee. Then they’d find a tactful way to ask me whether I’d ever seen the University of the South—all those steep hills and narrow stone steps.

I’d been intrigued by Sewanee for years. I’d already travelled great distances for my writing, seeking out programs and conferences in the Northeast and Midwest. During those years, I craved contrast. I needed points of reference that would challenge my ideas about what kind of writer I wanted to be. Before Sewanee, I’d never had the chance to do anything as a writer in Tennessee, my home state. But I was growing tired of having to travel so far in order to connect with my tribe.

I’d been intrigued by Sewanee for years. I’d already travelled great distances for my writing, seeking out programs and conferences in the Northeast and Midwest. During those years, I craved contrast. I needed points of reference that would challenge my ideas about what kind of writer I wanted to be. Before Sewanee, I’d never had the chance to do anything as a writer in Tennessee, my home state. But I was growing tired of having to travel so far in order to connect with my tribe.

But by the time I was finally heading to Sewanee—to be a writer on my home turf—the distance seemed incredibly vast. The day I arrived, I sat on my narrow dorm-room bed, iced down my legs, and tried to accept that this just wasn’t going to work. I would not be able to manage the stairs and the uneven paths and the hobbling from building to building. And the first few days seemed to bear out that fear. The pain was prohibitive at times. I was self-conscious about my cane and the reactions it provoked in others.

Anyone who has experienced visible disability knows that a wheelchair or cane makes you simultaneously conspicuous and invisible. With the cane, my presence clearly made some people uncomfortable. A few men who had flirted with me now wouldn’t meet my eye. Others of my peers, their eyes flicking constantly toward the cane, seemed noticeably impatient to schmooze with someone less encumbered. After all, the pace is fast at a writers’ conference, and self-consciousness isn’t reserved for those wearing ankle braces. Though I was hurt by these little slights, I also felt something unexpected. I became overcome by empathy for these peers, as they tried so hard to keep their cool. After all, they only wanted what I wanted: acceptance within this talented group of writers.

On the fourth day, however, my experience began to shift. I listened as playwright Daisy Foote gave a moving, deeply honest lecture about the unexpected detours she’d encountered in her own writing life. As she spoke, I began to breathe more deeply, finally seeing what was obvious: I was living through a significant detour of my own, and I would be a different writer when I reached the other side of it.

On the fourth day, however, my experience began to shift. I listened as playwright Daisy Foote gave a moving, deeply honest lecture about the unexpected detours she’d encountered in her own writing life. As she spoke, I began to breathe more deeply, finally seeing what was obvious: I was living through a significant detour of my own, and I would be a different writer when I reached the other side of it.

The writers who led my fiction workshop—Richard Bausch and Erin McGraw—exuded good-humored encouragement underpinned by rigorous insistence on the highest standards of craft. I was especially grateful to fall under the guidance of these two writers while I was in such a receptive, shifting state of mind. During a noisy, bustling reception, Erin encouraged me to write about my health ordeal in as many forms as I could: “We have to steal from ourselves, you know,” she said.

Bausch’s advice came as we sat on the porch swing at Stirling’s, the campus coffee shop. After discussing my manuscript with exceptional precision, Bausch listened as I described my experiences of being so ill and my curiosity about how I would change as a writer. As kindly as possible, he said, “Don’t be afraid. Use the wounds.”

Bausch’s advice came as we sat on the porch swing at Stirling’s, the campus coffee shop. After discussing my manuscript with exceptional precision, Bausch listened as I described my experiences of being so ill and my curiosity about how I would change as a writer. As kindly as possible, he said, “Don’t be afraid. Use the wounds.”

Many times since then I have tried to follow Bausch’s advice. But every time I attempted to shoehorn those experiences, by force of will, into thinly veiled short stories, the true-life events remained intractable. They would not bend to the needs of fiction. My injured protagonists seemed to become passive, martyred victims, or crass mouthpieces for all the darker, angrier impulses that all injured people want to shout out loud, even if they know they ought to behave like good patients. Either way, the stories were stale and artificial.

But a few weeks ago, just after I learned I would be returning to Sewanee again this summer, those pivotal life events of two years ago finally made their way into the novel I’m writing. Simply put, they occurred on their own, without my realizing what I’d done. This new material has disrupted my tidy schedule for completing the project but also, in the process, deepened the heart of the novel. I’d be a fool to complain.

Disruption is an inevitable feature of life, and writers would do well to embrace it. I claim no mastery of this virtue, although I intend to pursue it. The time I spent on the mountain with that group of writers helped me turn outward again, a necessary condition for healing, if only of the spirit. The cumulative effect of exciting readings, craft lectures, and high-spirited evenings with my peers had me walking around wide-eyed and itching to get back to the page. During workshop on one of the final days of the conference, I scribbled in my journal: “I’ve become someone who can gain entry to these rooms. How is that?”

Disruption is an inevitable feature of life, and writers would do well to embrace it. I claim no mastery of this virtue, although I intend to pursue it. The time I spent on the mountain with that group of writers helped me turn outward again, a necessary condition for healing, if only of the spirit. The cumulative effect of exciting readings, craft lectures, and high-spirited evenings with my peers had me walking around wide-eyed and itching to get back to the page. During workshop on one of the final days of the conference, I scribbled in my journal: “I’ve become someone who can gain entry to these rooms. How is that?”

Disbelief at one’s luck is easy to come by at a place like Sewanee, where the company of other writers never ceases to feel magical. Not only was there magic in the mountain air that week, there was good medicine—it was at Sewanee that I first experienced moments of walking without pain.

To be sure, Sewanee is a place where surprises can occur, and if you venture there you may be changed by the experience. You may be led into a graveyard to hear poetry read beneath a bright, haunting moon. A fellow writer in your workshop may make a casual comment on someone else’s story and upend your view of your own work. On your way out of town, you may catch a glimpse of a Pulitzer Prize-winner eating breakfast at a Waffle House counter. In short, your notions of what the writing life looks like might just get blown to smithereens, replaced by something richer, fuller, and maybe even a bit stranger.

This year’s conference, which will be held July 22-August 3, boasts a formidable lineup of writers—with readings open to the public—and I’ll be packing my bags to join them. When I head up the mountain this time, I’ll be ready to welcome the unexpected.

Emily Choate holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College, and her writing has appeared in Yemassee and Tennessee Libraries and is forthcoming in The Florida Review. She lives in her hometown, Nashville, where she’s working on a novel.

Sewanee photos copyright (c) Laurie Perry Vaughen, who is completing an M.F.A. in poetry at the Sewanee School of Letters. She teaches writing at Chattanooga State Community College.