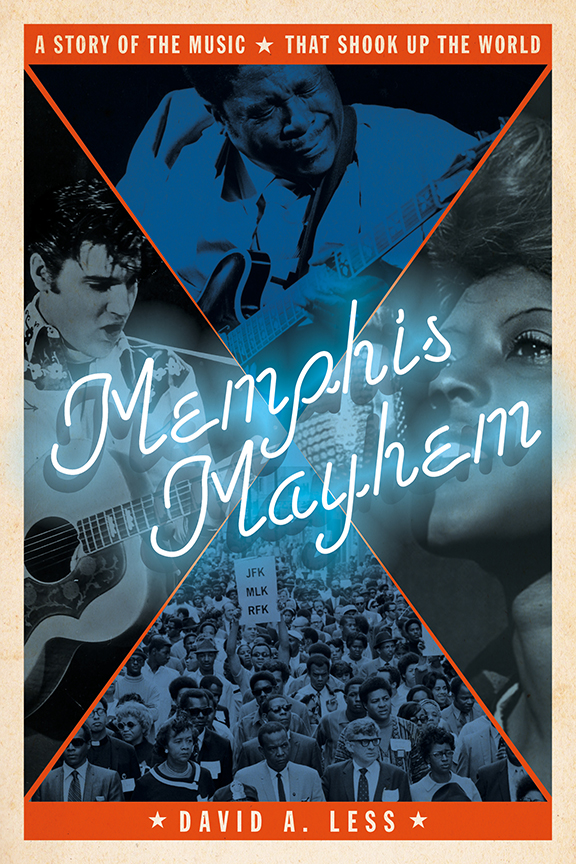

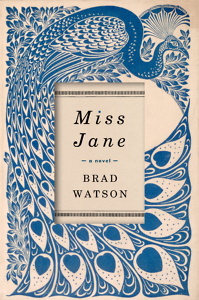

Her Own Strangeness

A baby girl born with an abnormality faces an uncertain future in Brad Watson’s Miss Jane

In an early scene in Brad Watson’s evocative novel, Miss Jane, a country doctor arrives home at dawn after spending a long night on the Chisholm family farm, where he has delivered a baby girl born with a genital abnormality. Returning home to find his yard crowded with injured and ill patients, all waiting for treatment, he marvels at the range of trouble facing his woebegone rural practice: “And all these wretched souls came out of the womb perfectly normal, the doctor thought, looking around. Who can say what life will make of a body?” Miss Jane offers a kind of answer to that question through the life of that baby girl, Jane Chisholm. In a bold yet delicate character study, Watson illuminates Jane’s world, as well as the internal terrain of those who know her best.

Watson deftly introduces us to Jane’s condition by enveloping it into the broader picture of Jane as a whole person. The opening pages of the novel establish a strong, detailed vision of her inner life by giving an inventory of the things she does not fear, ranging from the wildly various animals that run freely on her family’s farm to the hellfire threats of circuit preachers. Deep into this list, Watson turns to Jane’s “affliction”: “She did not like the vexation of her incontinence, and wished she would outgrow it, but eventually accepted it as part of who she was, no matter how unsavory,” he writes. “She did not fear her own strangeness, even though her awareness of it grew and evolved as she got older.”

Born near Mercury, Mississippi, in 1915, Jane soon learns that her social circle is likely to stay small. Though those who comprise that circle care for her, they also wrestle with their own problems. Sylvester, her father, feels the burdens of family life keenly and is prone to drinking the fine whiskey he makes in his still. Her mother, Ida, has succumbed to her own fears and darker thoughts. Eager to share her own perspective on their family is Jane’s older sister, Grace, whose clear ambition is to vacate the farm as fast as she can. And then there’s kindly Dr. Thompson, whose frequent counsel and determination to cure Jane mask his long-term reckoning with loneliness.

When the people around her don’t give her the information she needs, Jane turns to nature’s inhabitants. She observes their behavior and draws her own conclusions. She marvels at the ability of fish to breathe underwater, at their gills with the “strange blood-filled filaments that were apparently the secret to their magical abilities to live as they did.” What happens to fish born without gills? “If it just floated to the surface of the water and died,” she wonders.

When the people around her don’t give her the information she needs, Jane turns to nature’s inhabitants. She observes their behavior and draws her own conclusions. She marvels at the ability of fish to breathe underwater, at their gills with the “strange blood-filled filaments that were apparently the secret to their magical abilities to live as they did.” What happens to fish born without gills? “If it just floated to the surface of the water and died,” she wonders.

Eventually Jane comes to find a sensual understanding of the teeming natural world around her—the odd mushrooms shaped like phalluses, the rutting habits of the various farm animals. But even if she cannot yet express her feelings, sensual mysteries run deep for Jane: “She felt it inside herself … as deeply and truly as a lover. She fell into the grove’s rough, tall grass and into darkness, some charged current running through her in pleasant palpitations of ecstasy.” As Jane matures, the novel unfolds with tender confidence, and Jane’s curiosity—not to mention her strong will—expands to encompass her romantic life and the question of her future.

Miss Jane might easily have faltered—the premise of such a novel teeters on the point of a knife. If, on one side, the depiction of this character leans a hair too timid or squeamish, then we would strain to accept the reality of Jane’s experience. If, on the other side, the book were to indulge the prurient or exploitative, we would find many scenes unbearable, even enraging. But Watson overcomes three challenges of otherness—gender, historical era, and physical disability—and manages to illuminate Jane’s story with a particularly strong sense of intimacy, as well. From this intimacy, Watson creates a voice that we trust with Jane’s private world.

The novel travels deep into Jane’s internal landscape and stays there for a series of meditations on mortality, loneliness, and the seasonality of nature. In some ways, it becomes an atlas of Jane’s world. But Miss Jane also charts the voyage we all make toward self-acceptance and honest engagement with the world around us—or, as Jane imagines, the power to “absorb life from its center and its periphery at once”—so that we may “take it all in with the sweet fullness of the entirely human and the utterly strange, without apprehension or fear.”

Emily Choate holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College. Her fiction has been published in The Florida Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and The Double Dealer, and her nonfiction has appeared in Yemassee, Late Night Library, and elsewhere. She lives in Nashville, where she’s working on a novel.