High-Country Song

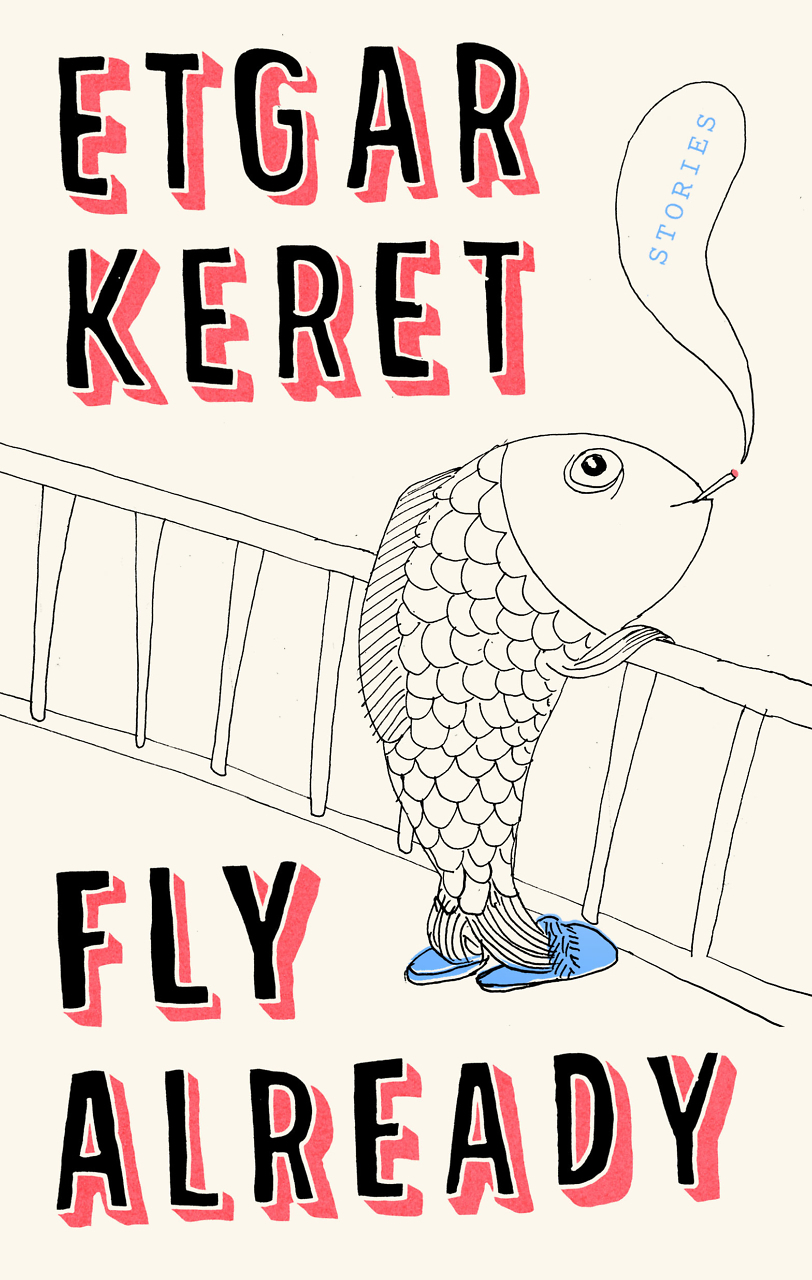

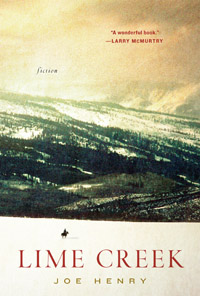

In his debut work of fiction, Lime Creek, renowned lyricist Joe Henry pays homage to stoic lives molded by the unyielding landscapes of the mountain West

We all know a few of those unforgettable country-folk songs: the ones that tell stories, the ones that move even the most cynical hearts by distilling universal hopes and fears into three-and-a-half minute narratives of hardship, tragedy, and survival. Joe Henry has made a career of his gift for penning precisely these kinds of lyrics. He has worked with a variety of artists in multiple genres, from Vince Gill and Garth Brooks to John Denver and Burt Bacharach, and his songs have been recorded by artists as disparate as Frank Sinatra and Rascal Flatts. In Lime Creek, his debut work of fiction, Henry translates his gift for the transcendent insight and the unforgettable turn of phrase into an extended meditation on the lives of a ranching family in the high country of the mountain West.

Lime Creek is neither a novel nor a collection of short stories per se; Henry’s subtitle for the book is simply “fiction.” It might be more accurate to describe these spare, lyrical snapshots in the lives of a rancher, his well-born Eastern wife, and his three sons as prose poems—or, perhaps, as something like song-stories. Each section of the book is built around a theme—“Family,” “Sleep,” “Passages,” “Love”—and each feels aimed at the same kind of emotional response derived from music. In fact, portions of the book have been staged in Prelude to Lime Creek, a spoken-word adaptation with musical accompaniment compiled and performed by actor Anthony Zerbe at the Denver Theater Company. Past Lime Creek Christmas, performances have featured Zerbe, John Denver, and Garth Brooks.

Henry’s objective is not an extended narrative, but rather a sort of literary album of critical moments in the lives of the Davis ranching clan: Spencer, the Wyoming-born, Harvard-educated patriarch; Elizabeth, the beauty who abandons a life of blue-blood privilege to join Spencer out west; and their three sons, Lonny, Whitney, and Luke. Each chapter’s theme is brought to light by a family anecdote, sometimes narrated by Spencer or Luke, Lime Creek’s central characters. The book begins with Spencer and Elizabeth’s love story and carries on through galvanizing moments in the family’s life together. Some, like “Tomatoes,” wherein the youngest two boys do what boys are naturally going to do when left alone with a pile of ripe red fruit and a target area of dangling bed-sheets, are comical coming-of-age moments. Some cover typical country-song territory, like “Love,” in which Luke experiences a tender sexual initiation on a snowy night in a motel room when his high school-football team gets stranded trying to get home after winning a playoff game.

Henry’s objective is not an extended narrative, but rather a sort of literary album of critical moments in the lives of the Davis ranching clan: Spencer, the Wyoming-born, Harvard-educated patriarch; Elizabeth, the beauty who abandons a life of blue-blood privilege to join Spencer out west; and their three sons, Lonny, Whitney, and Luke. Each chapter’s theme is brought to light by a family anecdote, sometimes narrated by Spencer or Luke, Lime Creek’s central characters. The book begins with Spencer and Elizabeth’s love story and carries on through galvanizing moments in the family’s life together. Some, like “Tomatoes,” wherein the youngest two boys do what boys are naturally going to do when left alone with a pile of ripe red fruit and a target area of dangling bed-sheets, are comical coming-of-age moments. Some cover typical country-song territory, like “Love,” in which Luke experiences a tender sexual initiation on a snowy night in a motel room when his high school-football team gets stranded trying to get home after winning a playoff game.

Others plumb darker depths—especially “Hands,” in which, while corralling cattle on a terrifically cold winter night, a bit of adolescent insolence sparks a father’s rage and precipitates a flood of memory that confronts his sons with the horror of his experiences as an infantryman in World War II. “We understood that there was nothing that could be said,” Luke recalls. “There was no word or string of words that a body could come up with that could in any way free someone of the memories that Spencer had had to live with. And that we in turn would now share with him for the rest of our own time unforgotten along with our own yet-to-be-discovered trials and misfortunes that are part and parcel of each and every one of us who tries to get through this life on just two legs. As if that awful and enduring gut-ache of human sorrow was just the going market-price for having the pride and presumption to think that with all the other creatures who needed all four legs to make it through on, that you could get’er done on just the two.”

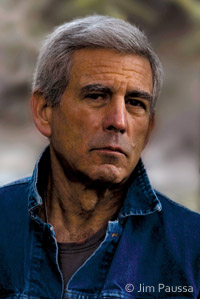

Though he’s logged time as a Nashville songwriter, Joe Henry is well-known as the genuine article: an ex-boxer and pro hockey player who has spent most of his life working with his hands in the territory where he stakes his musical and literary claims. His reverence for the West and his ability to translate its landscapes in sentences that are at once elegantly spare and rhapsodic make his work feel elegiac and worthy of its obvious influences. Henry’s prose vibrates with the chill of the high country air, the loud rush of the wind, and the urgency of everything in life for those who stake their claims in the shadows of the mountains.

Though he’s logged time as a Nashville songwriter, Joe Henry is well-known as the genuine article: an ex-boxer and pro hockey player who has spent most of his life working with his hands in the territory where he stakes his musical and literary claims. His reverence for the West and his ability to translate its landscapes in sentences that are at once elegantly spare and rhapsodic make his work feel elegiac and worthy of its obvious influences. Henry’s prose vibrates with the chill of the high country air, the loud rush of the wind, and the urgency of everything in life for those who stake their claims in the shadows of the mountains.

You get the sense reading Lime Creek that Joe Henry is not emulating Cormac McCarthy or Larry McMurtry so much as tapping into the same vein of inspiration that birthed their great western novels. Like McCarthy, Henry is irresistibly drawn to the homily and the philosophical aphorism—sometimes (though not often) to his detriment. There are moments in some of these story-songs where Henry might have done better to let the action suggest the necessary conclusion. The professional songwriter’s compulsion to resolve the narrative neatly and briefly gets in the way of the fiction writer’s credo to show rather than tell. At other points, Henry’s apparent need to explain the big lesson of the particular moment he has rendered on the page takes on a nearly biblical gravity. “Like it or not,” Luke tells us near the end of “Hands,” “you would learn what you were given the breath of life to learn. You would learn what you unknowingly came here to learn. And your sorrow and grief and your joys and pleasures too would teach you your lessons in a curriculum devised just precisely for you.” If this observation can be read as Henry’s thesis, it’s easy to understand why he’s been so successful as a songwriter, and why, despite the absence of so many of the traditional elements of the novel, Lime Creek resonates in memory like the last, sustained chord strummed on an old guitar in an empty room.