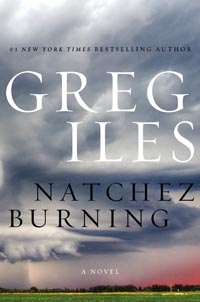

History, Meet Mystery

Greg Iles is back, and his new thriller channels the storytelling style of William Faulkner

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, Penn Cage—attorney, author, and mayor of Natchez, Mississippi—gets a phone call from the district attorney that will change his life forever and may also uncover many long-buried secrets from the South’s deadly civil-rights struggle: Penn’s father, Tom Cage, a Natchez family physician beloved by blacks and whites alike, is about to be charged with murder in the assisted suicide of the African-American woman who worked as his nurse forty years earlier.

Natchez Burning is the long-awaited new megathriller by New York Times bestselling author Greg Iles. Five years in the making, the book is the first in a trilogy whose themes of race relations, Southern tradition, and the corrupting nature of power are expertly woven throughout a story so powerful that its 800 pages seem less like a challenge than a gift. District Attorney Shad Johnson’s decision to pursue the case suggests that both the nurse’s death and Dr. Cage’s history may not be quite what they seem. Also not what he seems is the district attorney, and if Penn chooses to expose him, Johnson risks disbarment and criminal charges himself.

Penn Cage desperately struggles to help his father, but the elder Cage refuses to tell his son what happened on the night he went to treat his former nurse, Viola Turner. So the mayor confers with newspaper editor Henry Sexton, who interviewed Turner twice in the weeks before her death and who knows more about the town’s secrets than any local or federal authority: “For the past five years, in the pages of the little weekly newspaper he’d once delivered from a bicycle as a boy, [Henry] had been publishing stories about the group he considered the deadliest domestic terror cell in American history,” Iles writes. “And people were starting to pay attention. Henry’s successes had embarrassed certain government agencies—the FBI, for example—and they had let him know it.”

Penn Cage desperately struggles to help his father, but the elder Cage refuses to tell his son what happened on the night he went to treat his former nurse, Viola Turner. So the mayor confers with newspaper editor Henry Sexton, who interviewed Turner twice in the weeks before her death and who knows more about the town’s secrets than any local or federal authority: “For the past five years, in the pages of the little weekly newspaper he’d once delivered from a bicycle as a boy, [Henry] had been publishing stories about the group he considered the deadliest domestic terror cell in American history,” Iles writes. “And people were starting to pay attention. Henry’s successes had embarrassed certain government agencies—the FBI, for example—and they had let him know it.”

During the 1960s, Dr. Cage’s nurse and her brother were victims of a sadistic attack by a local cabal that made the Ku Klux Klan look like a garden club. Though Viola Turner escaped afterward to Chicago, where she stayed until returning to Natchez to die, the group known as the Double Eagles—many of them still alive—had murdered her brother, whose body was never found. “Founded in 1964, the Eagles were an ultrasecret splinter cell of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan,” Iles writes. “In forty-one years, only a few members’ names had been discovered, and none had been confirmed.” Henry’s persistent efforts to identify the Double Eagles have earned him the disdain of many of the locals. Some of them are racists, of course; the others simply resent him for “stirring up the past for no good reason.’”

Iles, who lives in Natchez, writes with an erudite knowledge of the civil-rights movement and a firm command of Southern history generally and of Natchez history specifically. Informed readers will delight in the rich character development and deeply textured plot, while those unfamiliar with the nuances of Deep South racism will learn why things are the way they are in a town that was spared destruction after surrendering to the Union during the Civil War.

Iles, who lives in Natchez, writes with an erudite knowledge of the civil-rights movement and a firm command of Southern history generally and of Natchez history specifically. Informed readers will delight in the rich character development and deeply textured plot, while those unfamiliar with the nuances of Deep South racism will learn why things are the way they are in a town that was spared destruction after surrendering to the Union during the Civil War.

At times, in fact, the book feels as much like historical fiction as masterful suspense, as Iles deftly delivers backstory not only to the mystery at the heart of Natchez Burning but also to his own little postage stamp of native soil: “It was during the fifties that a nasty streak of racism had taken root in Natchez. The seeds of that sentiment had come from outside the town proper. Though Natchez had been the slaveholding capital of the South, its leaders were Anglophiles who sympathized with the Union cause,” Iles writes. “But by the 1950s, large numbers of poor whites had been brought in to work in the town’s manufacturing plants, and with them came the extreme and sometimes violent prejudice of the working class. Hailing from places like Liberty, Mississippi, and Monroe, Louisiana—hard-shell Baptist country—these descendants of the archetypal Confederate foot soldier were the disaffected ranks that Klan recruiters found ready for action when the Negro started trying to achieve equal rights in the workplace.”

According to novelist Scott Turow, Natchez Burning brings to mind the storytelling brilliance of William Faulkner and Thomas Wolfe. Though Turow and Iles are friends—they were both members of the now-disbanded literary musical group known as the Rock Bottom Remainders—such comparisons aren’t hyperbole. Natchez Burning is perhaps the best thriller to come along in years. Memorable, intricate, and expertly crafted, it is a goliath of a book, and not just for its 800-page heft.

Greg Iles will discuss Natchez Burning at The Booksellers at Laurelwood in Memphis on May 1, 2014, at 6 p.m.